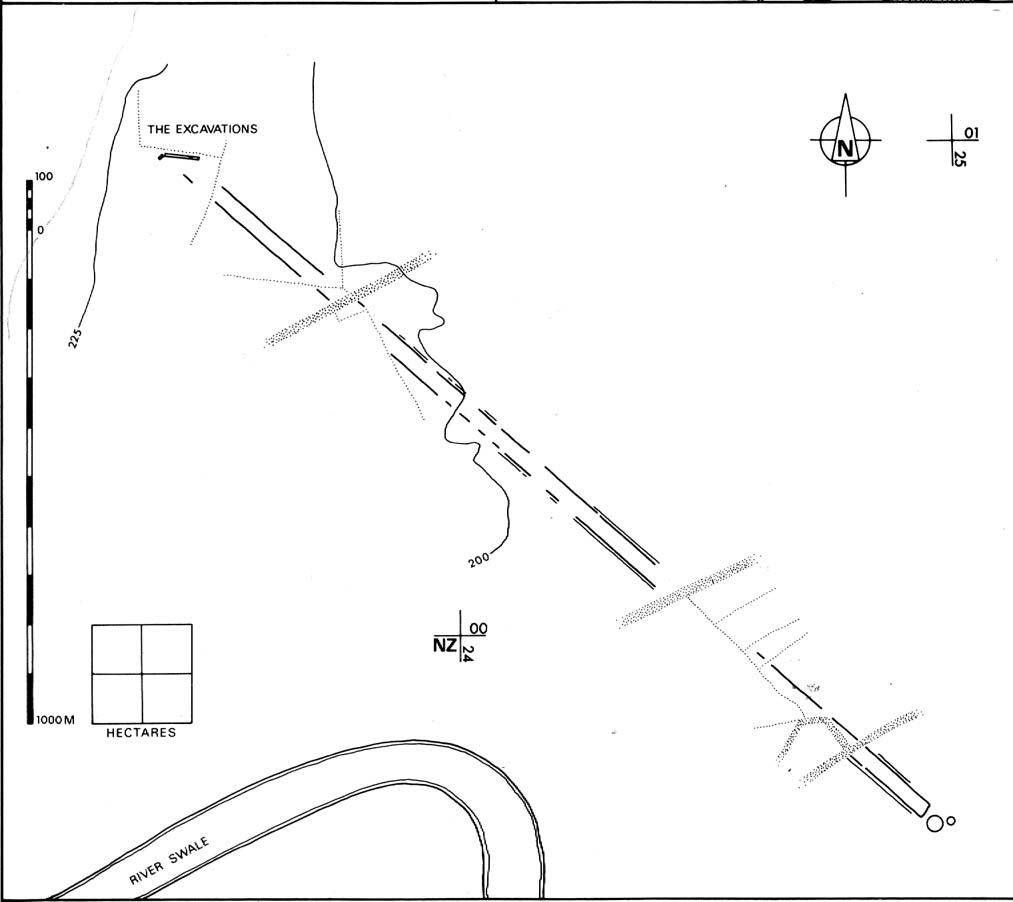

Cursus: OS Grid Reference — TA 0998 6577 to TA 1016 6802

Also known as:

- Beacon Cursus

- Rudston Cursus 1

- Woldgate Cursus

Archaeology & History

The site has been known about for nearly 150 years, albeit mistakenly as a series of prehistoric barrows that William Greenwell (1877) told were “near the division between the parishes of Rudston and Burton Agnes” near the crest of the hill. He further told the place to be,

“Two long mounds, almost parallel, their northern end gradually losing themselves in the surface-level, but connected together at the southern end by another long mound.”

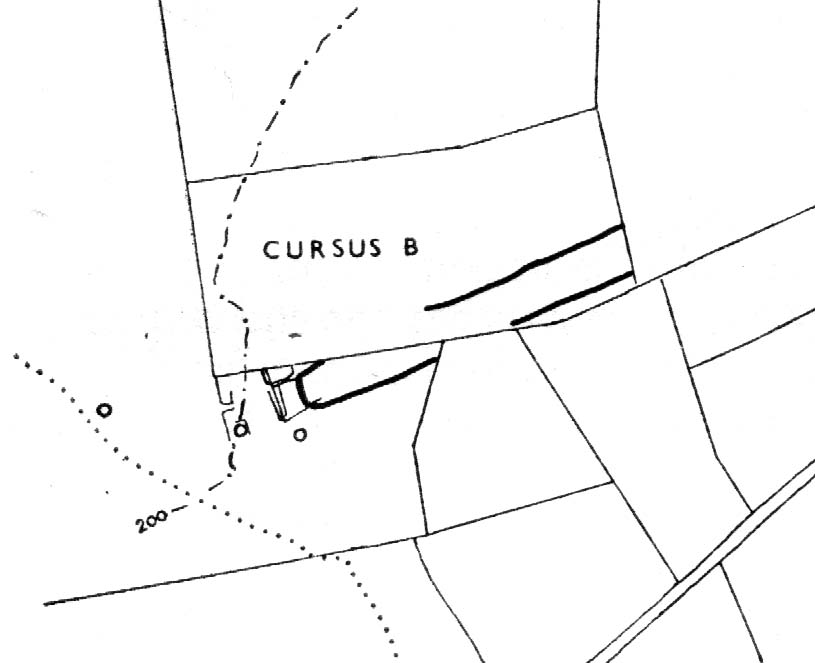

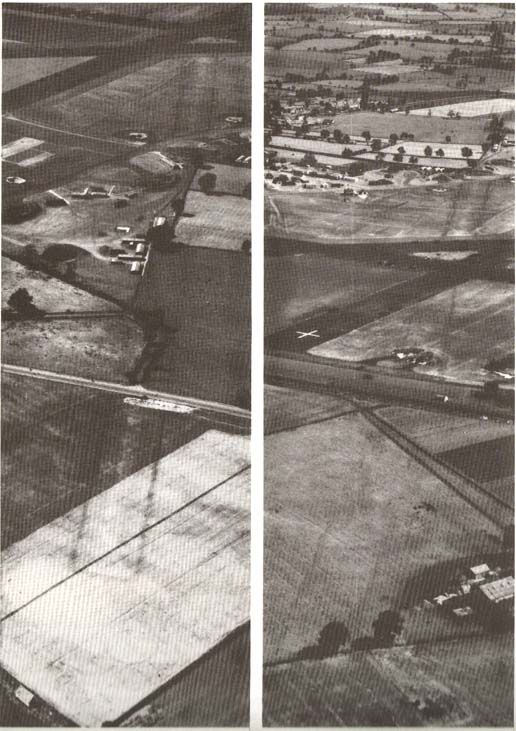

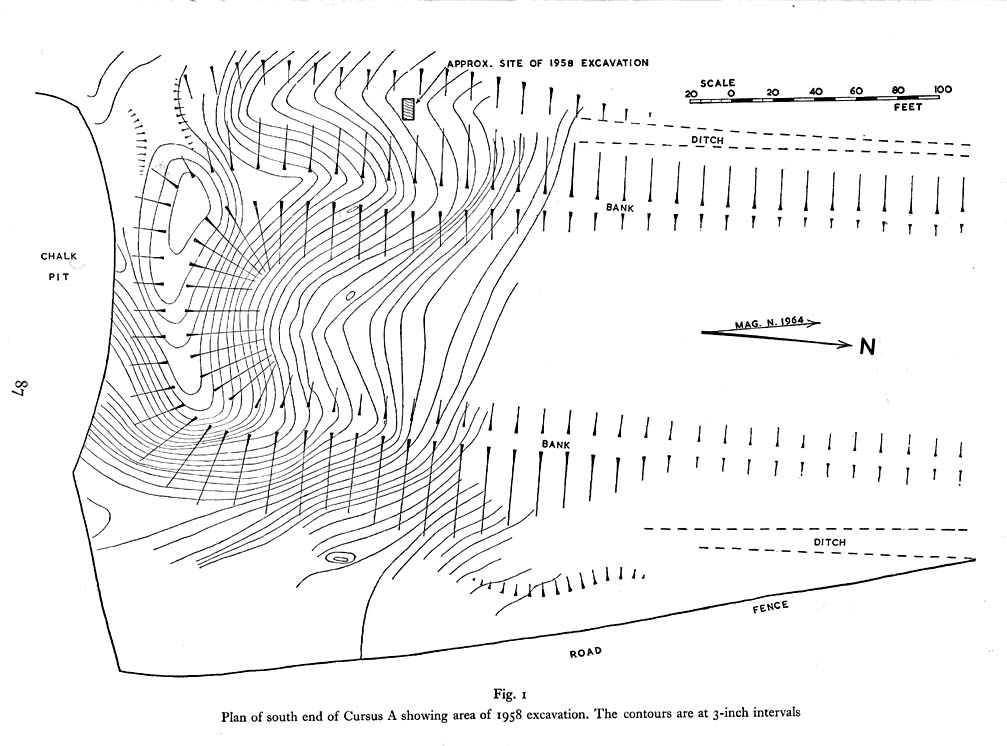

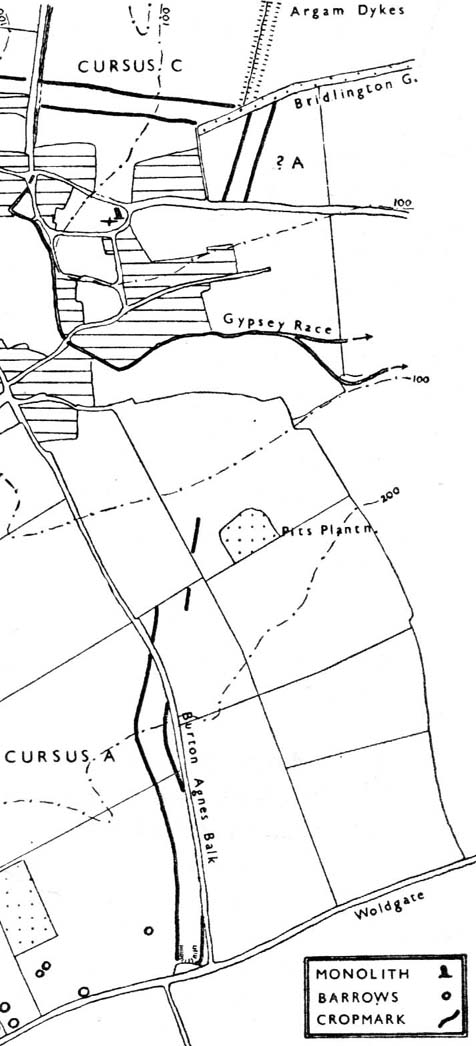

Then in 1958 when C. & E. Grantham of Driffield did the first modern excavation here across a section of the western ditch, they found that the long embankment went on much further than ever previously anticipated, for more than half-a-mile downhill in the direction of Rudston village. It wasn’t a long barrow or tombs of any sort, they found! Then in 1961 when Dr. J.K. St. Joseph did aerial survey work over the area, he and his colleagues established that this monument consisted of extensive parallel ditches stretching for at least 1½ miles towards and past the eastern side of Rudston village. It’s nature as a cursus monument was rediscovered after several thousand years in the wilderness… (on St. Joseph’s survey, two other cursus monuments were also found in the vicinity, being Rudston Cursus B and Cursus C) Readers will hopefully forgive me for quoting at some length Mr Dymond’s (1966) article on the site (with minimal editing!):

“The southern end of the cursus lies in the western angle of two roads, Woldgate and Burton Agnes Balk. In plan it is square with rounded corners and consists of a bank with outer ditch. Although the bank has been ploughed for many years, it still remains substantial; it stands up to 4 feet high from the outside and 1-2 feet wide from the inside. The east and west banks decline in height northwards and are now at their greatest height where they join the southern end. The profile of each bank is smooth and rounded and merges on the outside with the broad shallow depression of the silted-up ditch. The south bank is now 170 feet long overall, and spread to a width of 60-80 feet. It stands higher at both ends than in the middle. This fact was noted by Greenwell, who also recorded that at the southwest angle “there was the appearance of a round barrow raised upon the surface of the long mound.” There is no surface evidence today to suggest a secondary round barrow, and to some extent at least the greater height at the angles is probably due to the concentration of upcast inside a fairly sharp corner.

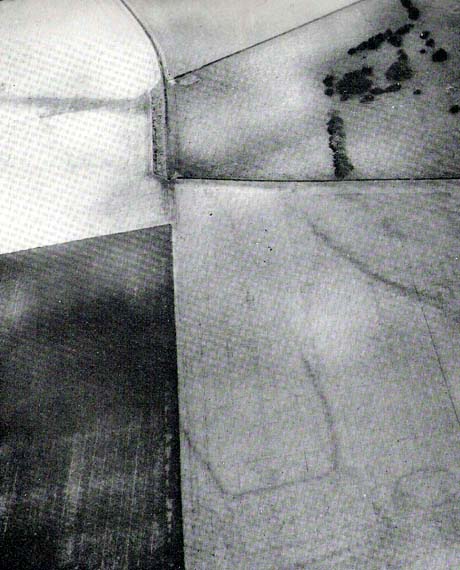

“The south arm of the ditch has been largely destroyed by a chalk-pit, but the southeast turn is quite clear on air-photographs. There is no suggestion on the ground or from the air that the cursus had ever extended further to the south.

“The cursus begins its descent in a due northerly direction, and loses its eastern side for approximately 600 feet under the enclosure road, Burton Agnes Balk. The ditch can be traced intermittently on the western and eastern verges. It then swings gently NNW around the head of a small slack draining northwest. Thus far the cursus is traceable on the ground. The ditches are the most consistent feature, showing as broad shallow depressions 20-40 feet wide and 70-80 yards apart, which when in fallow attract a dark coarse vegetation (particularly thistles and nettles. The banks inside the ditches are sometimes visible in relief though considerably spread. Where the banks have been almost entirely ploughed out, a chalk spread usually marks their position.

“There is a suggestion on the ground that the banks and ditches may have been separated by berms, particularly on the east side near the square end. This appears to be confirmed by the silting of the ditch in the excavated section…

“Proceeding further downhill in the direction of Rudston village, the cursus quite suddenly swings north-NNE, finally crosses Burton Agnes Balk, and passes to the west of Pits Plantation. On the west of the road both banks and ditches are still visible in relief, and the ditches produce a firm crop-mark. East of the road no surface traces are discernible, and only the eastern ditch shows intermittently as a crop-mark.

“For ½-mile across the floor of the Great Wold Valley, there is no trace of the cursus. The area has been ploughed since medieval times, and there is in addition a considerable Romano-British settlement. It is worth noting that in this length, the cursus must have crossed the stream of the Gypsey Race, surely a fact of some importance in any discussion of the function of cursuses.

“Two parallel ditches c.60 yards apart, visible on air photographs in a field immediately north of the modern Rudston-Bridlington road, seem to represent the continuation of the cursus. The ditches travel for approximately 300 yards and end at the Bridlington Gate Plantation. There are no surface traces in the field, but a depression in the plantation may represent the eastern ditch. This depression is crossed obliquely by the remains of a low bank and ditch running along the length of the plantation WSW and ENE. This latter (part) is probably part of the supposedly Iron Age entrenchment system, and has certainly been used as a road from Rudston to Bridlington, as the name of the plantation implies.

“The northern end of the cursus cannot be traced. Possibilities are that the end was in the plantation and has been destroyed by the later earthwork, or that the cursus proceeded NNE for an unknown distance. If the latter hypothesis is accepted, the western ditch must be under the Argam Dykes, a double entrenchment which appears to terminate at the northern side of the plantation, and the eastern ditch is indistinguishable from ploughing lines to which it is parallel…

“Cursus A has its southern end at a height of 254 feet OD, on the forward face of a long chalk ridge running WSW and ENE. From this point the course of the cursus is visible, except for that part west of Pits Plantation. The last known part in Bridlington Gate Plantation, 1½ miles off, is clearly visible. Seen against the contours of the area, the cursus has one end resting on a high ridge, crosses a broad valley, and climbs at least in part, the far side. It appears to pass approximately 300 yards east of the monolith in Rudston churchyard.”

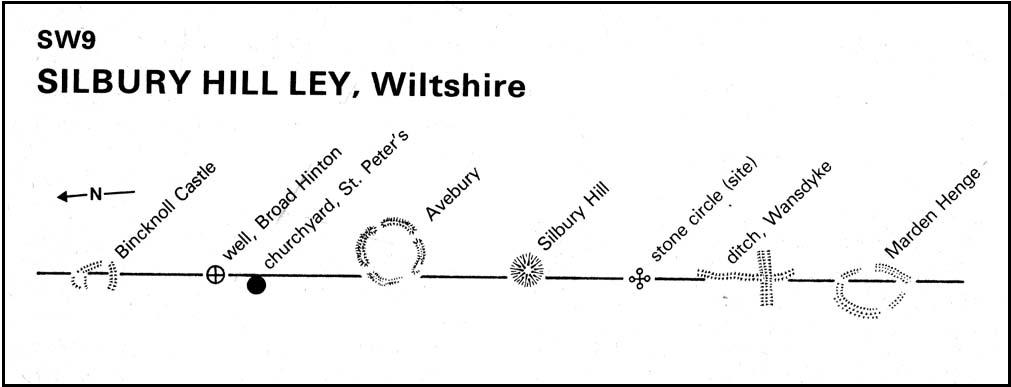

The presence of this and three other cursus monuments close by (Rudston B, C and D) indicates that the region was an exceptionally important one in the cosmology of our prehistoric ancestors. Four of these giant linear cursus monuments occur in relative proximity, and there was an excess of ancient tombs and, of course, we have the largest standing stone in the British Isles stood in the middle of it all. A full multidisciplinary analysis of the antiquities in this region is long overdue. To our ancestors, the mythic terrain and emergent monuments hereby related to each other symbiotically, as both primary aspects (natural) and epiphenomena (man-made) of terra mater: a relationship well known to students of comparative religion and anthropology who understand the socio-organic animistic relationship of landscape, tribal groups and monuments.

References:

- Dymond, D.P., “Ritual Monuments at Rudston, E. Yorkshire, England,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 32, 1966.

- Eliade, Mircea, The Sacred and the Profane, Harvest: New York 1959.

- Greenwell, William, British Barrows, Clarendon Press: Oxford 1877.

- Hedges, John & Buckley, David G., The Springfield Cursus and the Cursus Problem, Essex County Council 1981.

- Nicholson, John, Beacons of East Yorkshire, A. Brown & Sons: Hull 1887.

- Pennick, Nigel & Devereux, Paul, Lines on the Landscape, Hale: London 1989.

Links: – ADS: Archaeology of the Beacon Cursus, or Rudston A – Notes on the cursus which has been given the most attention to date.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.