Legendary Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 50 38

Also Known as:

- Clach an Dlogh

- Wart Stone

Archaeology & History

There is no written history of this site; only the quiet murmurings of a few locals whose families go back to when the english came and destroyed the people and their lives in the 18th and 19th century in the ethnic cleansing we known as The Clearances. As with the Darach nan Sith (the Oak of the Fairies) a few miles away, the local traditions were lost, and ancient monuments destroyed. Thankfully, due to the remote location of this site, its status remains….

It is found 2000 feet up, near an old derelict village (english academic romancers term it as ‘sheilings’). An ancient track and stone bridge runs over the burn nearby, place-names evidence tells of a prehistoric tomb a few hundred yards west, and there’s a dispersal of forgotten human evidences scattering the south-side of the mountain all along here. The clach (stone) sits on the very top of a large earthfast rock; is an elongated loaf-sized smooth red-coloured stone, about 14 inches long and 8 inches wide, and of a different type and much heavier than the local rock hereby. It is said to have been a healing stone, used in earlier times to cure warts and other ailments.

Folklore

My first venture here was, like many in this area, amidst a dreaming. Those who amble the hills properly, know what I mean. I cut across the mountain slopes diagonally, zigzagging as usual, always off-path, resting by mossy stones and drinking the waters here and there. My nose took me to the mass of giant rocks hedging into the higher regions of Allt Ghaordaidh: a pass betwixt the rounded giants of Meall Ghoaordie and Meall Cnap Laraich, where only eagles and Taoist romancers might roam.

The great rock comes upon you pretty easily. Approaching it for the first time I wondered whether there might be petroglyphs on or around it, but the rich depth of lichens and its curious crowning elongated stone stopped any further thought on the matter. The setting, the eagles, the colour of day and the fast waters close by, stole all such thoughts away. In truth I must have walked back and forth and near-slept below the place for an hour or two before I gave way to rational focus! And then my curiosity got even more curious.

“This must be the place,” I mused, several times.

As you can see in the photo, a large natural earthfast boulder, six feet high or more, like a giant Badger Stone covered in centuries of primal lichens, has a large deep red-coloured stone on its very crown. The stone is unlike any of the local rock and is very heavy. I found this out when trying to prize it from its rocky mount, dislodging it slightly from the seeming aeons of vegetation that held it there. But the moment I moved it, just an inch or so above its parent boulder, a quiet voice inside me rose sharply into focus.

“You shouldn’t have done that!”

Quickly I set it back into place, shaking my head at what I’d done. One of those curious feelings you get at these places sometimes wouldn’t leave me, however much I tried to shake it off. …Silly though it may sound, the echoes inside kept saying over and over to me, “you’re gonna get warts now you’ve done that!” Logically, of course, that made no sense whatsoever. I’d only ever had one wart in my life, a couple of decades ago. And yet, a few days later, one of the little blighters emerged on my finger! So there was only one thing for it! If this was a Wart Stone, I should revisit it again and place my afflicted finger back onto the wart and ask it to be taken back into the stone.

A week or so later, I clambered all the way up the mountainside again and asked the place to forgive my stupidity and take back the wart. Apologising to the spirit of the stone, I rubbed my finger on the curious coloured rock and, I have to be honest, didn’t know what to expect.

I spent the next few hours meandering here and there over the hills and cast the thought of the Wart Stone back into my unconscious. But a few days later it had started shrinking – and within a week, had completely gone! This faint relic of an older culture, this Clach na Foinne had performed its old ways again, as in animistic ages past…

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.

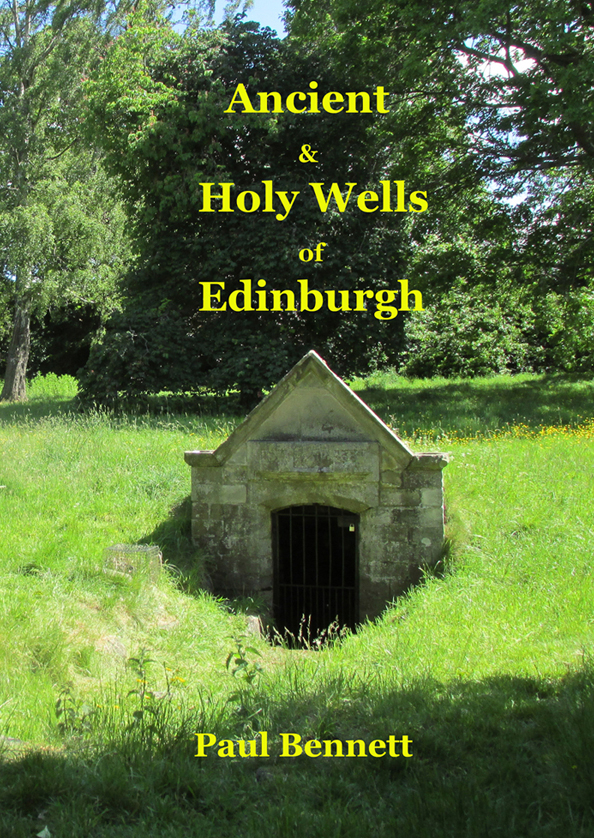

This is the first detailed guide ever written on the holy wells and healing springs in and around the ancient city of Edinburgh, Scotland. Written in a simple A-Z gazetteer style, nearly 70 individual sites are described, each with their grid-reference location, history, folklore and medicinal properties where known. Although a number them have long since fallen prey to the expanse of Industrialism, many sites can still be visited by the modern historian, pilgrim, christian, pagan or tourist.

This is the first detailed guide ever written on the holy wells and healing springs in and around the ancient city of Edinburgh, Scotland. Written in a simple A-Z gazetteer style, nearly 70 individual sites are described, each with their grid-reference location, history, folklore and medicinal properties where known. Although a number them have long since fallen prey to the expanse of Industrialism, many sites can still be visited by the modern historian, pilgrim, christian, pagan or tourist.