Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NR 83667 93576

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 212008

- Dunadd 2a (Morris)

From Lochgilphead, take the A816 road north for several miles (towards the megalithic paradise of Kilmartin), keeping your eyes peeled for the road-signs saying “Dunadd.” Turn left and park-up a few hundred yards down. Go through the gate and walk up Dunadd. Just before the flattened plateau at the top you’ll come across a length of smooth stone, adjacent to the Dunnad Footprint Stone, with a deep large circular ‘bowl’ cut deep into the rock. That’s the spot!

Archaeology & History

This large ‘bowl’ or basin just below the top of Dunadd—next to the other carvings of footprint, Ogham and boar—is speculated by many to have been a part of the kingship rituals that were alleged to have occurred up here, going way back. But please remember that ‘kingship’ as it was in ages past has nothing to do with the touristy nonsense that prevails in the UK today. Kingship in its early forms relates to rituals for the benefit of the tribe/society, in many cases resulting in sacrifices. (see Frazer 1972; Hocart 1927; Quigley 2005, etc) This is quite probably what occurred at Dunadd. But whether this curious deep bowl with its semi-circular carved ring had anything to do with the kingship rites, we simply don’t know.

An early description of the Dunadd Basin is in Mr Thomas’ (1879) essay on the hill itself. It was a brief note:

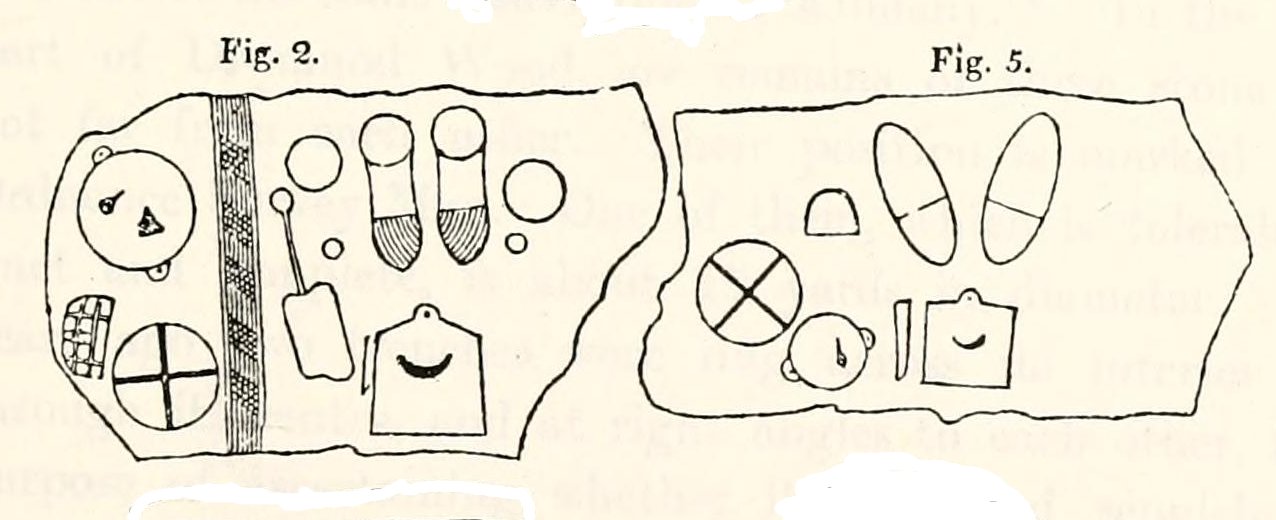

“About four yards southwards from the (Dunadd) footmark is a smooth-polished and circular rock basin cut in the living rock; it is 11 inches in diameter and 8 inches deep.”

There is no mention of the incomplete ring which, though faded, can be seen to surround two-thirds of the hollow. And as Dunadd was used by people until medieval times (Lane & Campbell 2000) it not only begs the question: when was it carved; but also: was the myth behind this petroglyph still alive? We’ll probably never know.

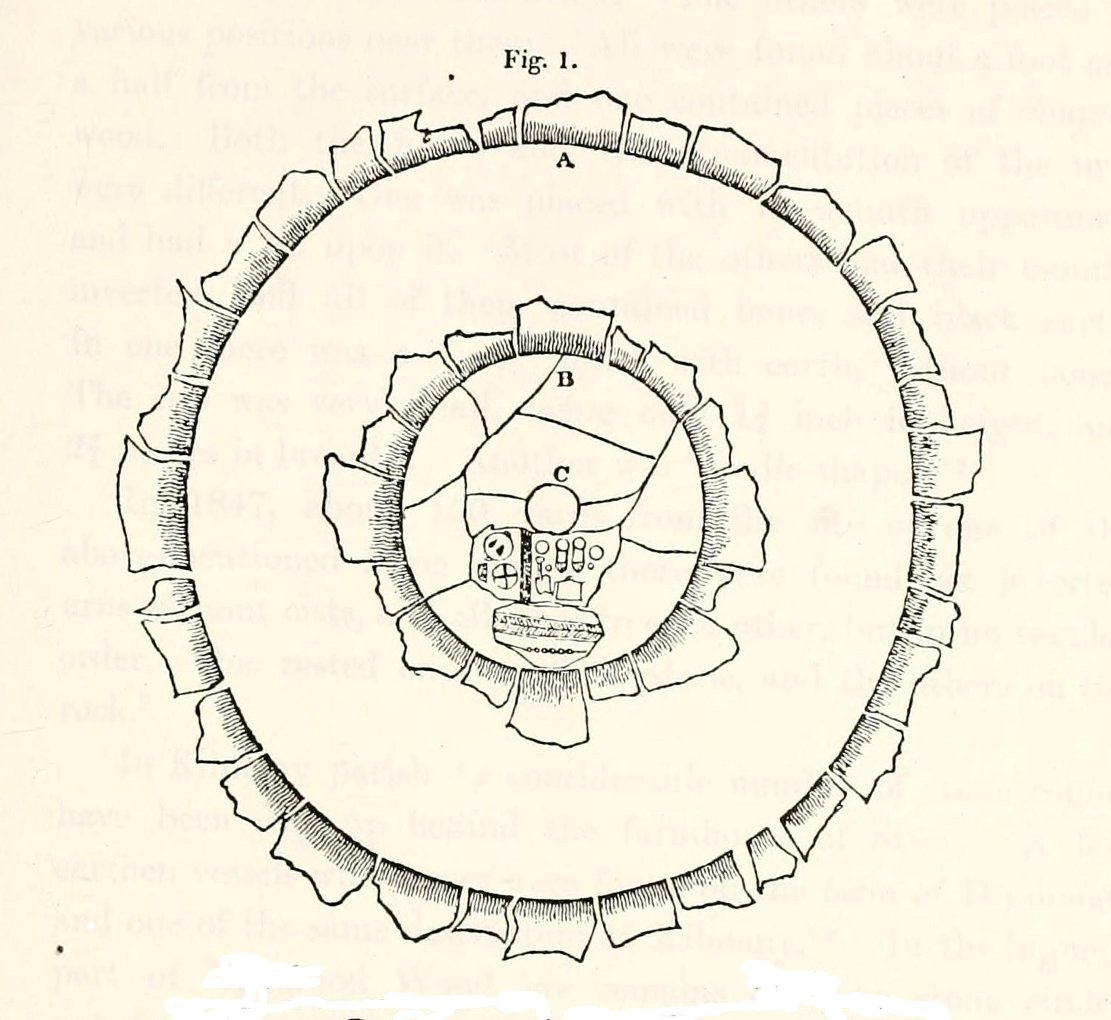

The Royal Commission lads (1988) said the following:

“The rock-cut basin measures 0.25m in diameter by 0.14m in depth, and is bisected by a crack. It is surrounded by a shallow pecked ring about 40mm in width, but parts of this have been worn away, especially to the S where the path from (the) enclosure passes the basin.”

Folklore

The basin here was said by the incoming priest R.J. Mapleton (1860) to be entirely natural in origin; though he also noted how Dunadd was known by local people to be the meeting place of witches and the hill of the fairies, whose amblings in this wondrous landscape are legion. Legends and history intermingle upon and around Dunadd. Separating one from the others can be troublesome as Irish and Scottish Kings, their families and the druids were here. One such character was the ever-present Ossian. Mapleton told:

“From these ancient tales we turn to a much later period of romance, when Finn and his companions had developed into extraordinary and magical proportions; a story is current that when Ossian abode at Dunadd, he was on a day hunting by Lochfyneside; a stag, which his dogs had brought to bay, charged him; Ossian turned and fled. On coming to the hill above Kilmichael village, he leapt clean across the valley to the top of Rudal hill, and a second spring brought him to the top of Dunadd. But on landing on Dunadd he fell on his knee, and stretched out his hands to prevent himself from falling backwards. ‘The mark of a right foot is still pointed out on Rudal hill, and that of the left is quite visible on Dunadd, with impressions of the knee and fingers.'”

As Mr Thomas clarifies: “The footmark is that of the right foot, and the adjacent rock-basin is the fabulous impression of a knee.”

References:

- Bord, Janet, Footprints in Stone, Heart of Albion Press 2004.

- Campbell, Marion, Mid-Argyll: An Archaeological Guide, Dolphin Press: Glenrothes 1984.

- Campbell, M. & Sanderman, M., “Mid-Argyll: An Archaeological Survey,” in Proceedings of the Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 95, 1962.

- Craw, J.H. “Excavations at Dunadd and other Sites,” in Proceedings of the Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 64, 1930.

- Lane, Alan & Campbell, Ewan, Dunadd: An Early Dalriadic Capital, Oxbow: Oxford 2000.

- Mapleton, R.J., Handbook for Ardrishaig Crinan Loch Awe and Pass of Brandir, n.p. 1860.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Argyll, Dolphin Press: Poole 1977.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – Volume 6: Mid-Argyll and Cowal, HMSO: Edinburgh 1988.

- Thomas, F.W.K., “Dunadd, Glassary, Argyleshire: The Place of Inauguaration of the Dalriadic Kings,” in Proceedings of the Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 13, 1879.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.