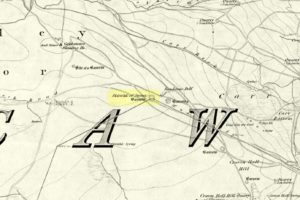

Hillfort: OS Grid Reference – SE 0925 4947

Two main ways to get here. Hmmmm….on second thoughts, one main way. My preferred route would be from Addingham (east-side) where the foot-bridge crosses the Wharfe. Walk up the path and, eventually, onto the tidgy road and bear left till you hit the trees. On the right-hand side of the road you’ll see the trees covering the crop near the edge of the river. …Otherwise, come from Ilkley, cross the river, take the first left, on a few hundred yards and left again on Nesfield Road. From here, keep walking about a mile and when you hit the village, you need to look into the field behind the first farmhouse on your left.

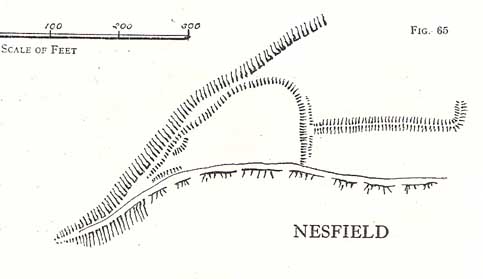

Archaeology & History

You’ll see the more visible embankments on the western edge of these old earthworks. But unless you’re a real archaeomaniac into depleted field remains, this might not tickle your neurons too much. However, it’s a gorgeous little hamlet is Nesfield – and I think that alone makes it worthy of a visit!

Described variously over the years as an enclosure, a hillfort, a camp, a settlement – aswell as being ascribed to periods from the medieval, Roman, Iron Age and Bronze, the consensus opinion at the moment edges to it being late Bronze- to early Iron Age in origin.

The fortifications themselves seem to have been first mentioned by T.D. Whitaker in 1812, who said the following:

“Castleberg is in a commanding position, on the brink of a steep slope washed by the Wharfe, about two miles above Ilkley. This post is naturally strong, as the ground declines rapidly in every other direction. But it has been fortified on the more accessible sides by a deep trench, enclosing several acres of ground, of an irregular quadrangular form. At a small distance within the enclosure, an urn with ashes was lately found, but what seems to evince beyond a doubt, the Castleberg was a Roman work, is the discovery of a massy key of copper, nearly two feet in length, which,” he thought, “had probably been the key of the gates.”

This ‘key’ that Whitaker mentioned (if memory serves me right) has been lost and therefore its nature/function lost aswell. E.T. Cowling (1946) thought the key “may refer to a bronze article of a size which must belong to the Late Bronze Age, when the metal became more plentiful”; thinking it perhaps to be part of a sword. Twouldst be good to find this artifact and know for certain. Cowling also posited that the urn found here was of Bronze Age origin – an opinion echoed by later archaeologists.

The great Harry Speight (1900) meanwhile, told that the hamlet itself was locally called Castleberg and told us a bit more of the details of the finds, saying:

“I am disposed to think it was a winter-station of the old Britons of Howber, and afterwards of the Teutonic settlers. An urn containing ashes has been found on the site, and Mr James Pickard, who has long occupied the adjoining farm, tells me he has excavated several parts of it and found human bones, but no relics. This premises Anglo-Saxon interments and the urn late British…”

References:

- Cowling, E.T. Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Howson, William, An Illustrated Guide to the Curiosities of Craven, Whittaker: Settle 1850.

- Keighley, J.J., ‘The Prehistoric Period,’ in Faull & Moorhouse’s, West Yorkshire, An Archaeological Guide, vol.1, Wakefield 1981.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

- Whitaker, T.D., History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven, J. Nichols: London 1812.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.