Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – SU 1343 7152

We were fortunate & taken here by the renowned local megalith authority, Pete Glastonbury – but without Pete’s help you might be ambling here & there for quite a while. It’s on the eastern side of The Ridgeway, down the slope past the stone known as The Polisher, across the flatland sea of many rocks until it begins rising again a few hundred yards east. Where a long straight embankment rises up a few feet (a boundary line), the rock’s just a few yards above it. Walk around!

Archaeology & History

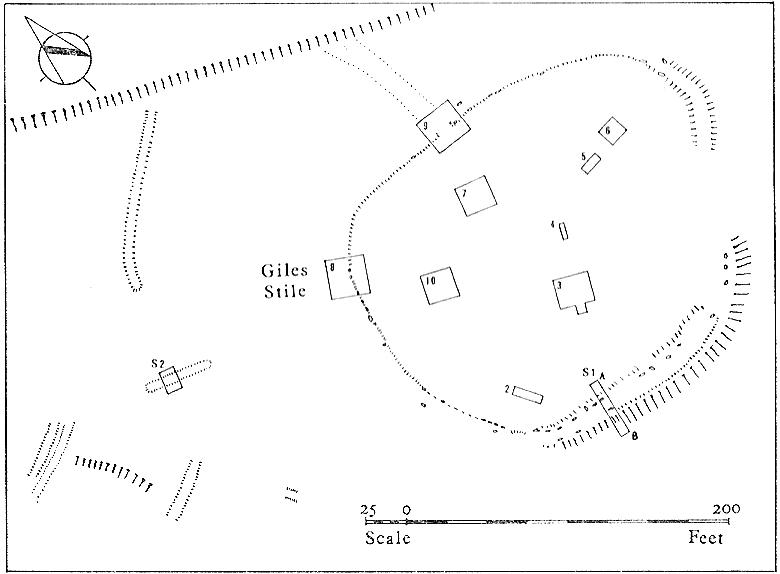

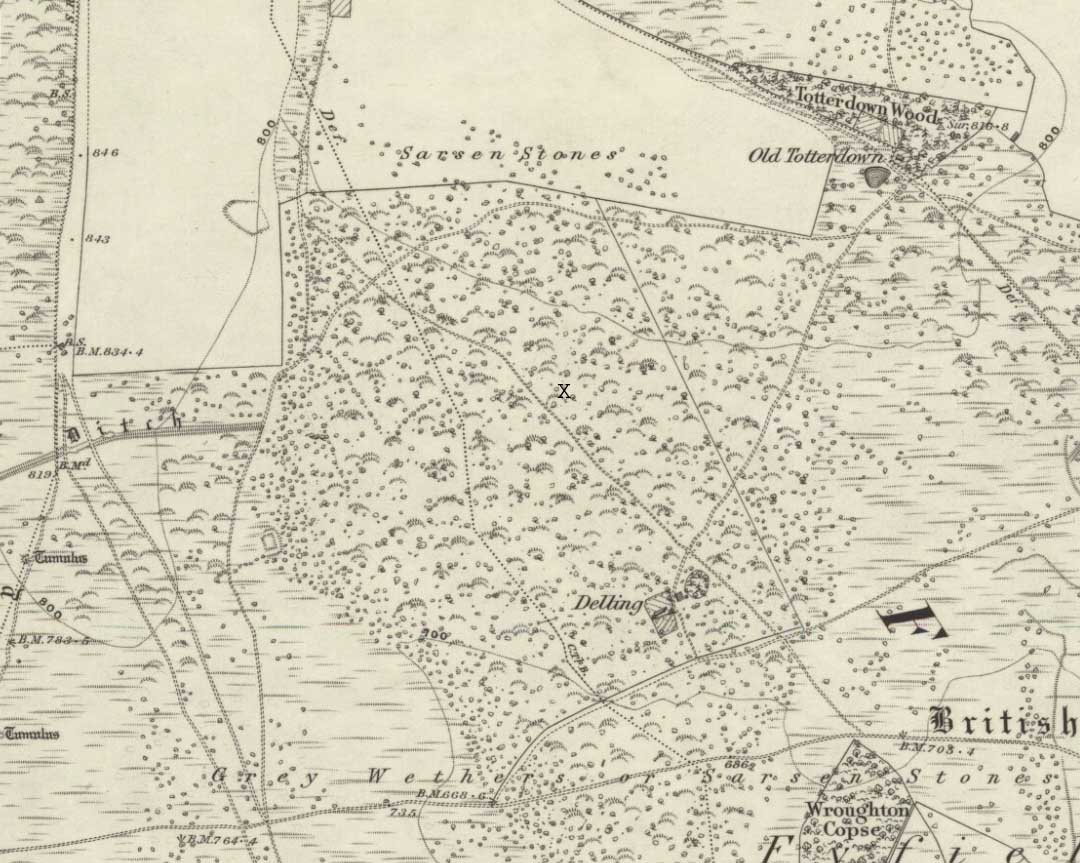

Archaeologist A.D. Lacaille (1962) appears to have been the first person to have written about this little-known site, describing it as being “between the south-western corner of Totterdown Wood and Delling Cottage.” Here is what he described as,

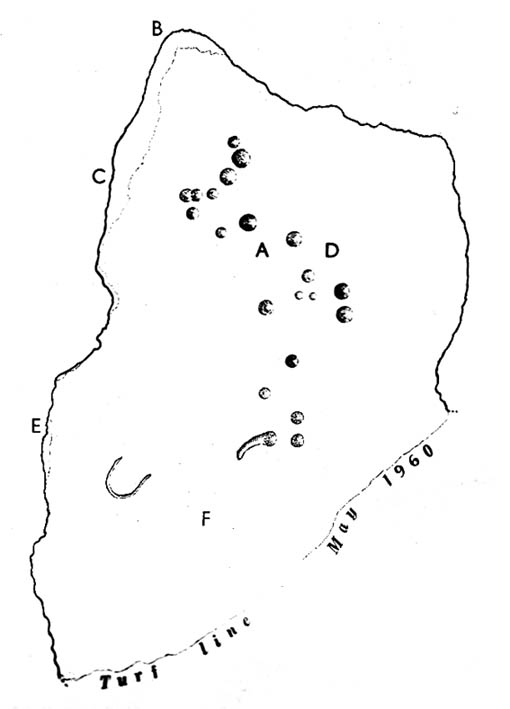

“a cluster of unmistakably artificial and mostly well-preserved cup-markings on the smooth south-easterly sloping surface of a recumbent sarsen.”

And from the photos accompanying Lacaille’s article, it obviously looked a decent carving as well — and so it has transpired. Lacaille (1963) briefly mentioned the carving again a year later in his lengthier essay on the nearby Polisher Stone up the slope a few hundred yards away. But then Wiltshire’s only known cup-marked stone was all-but ignored by archaeologists and left in the literary wilderness until, years later when rock art became a fad in such circles, regional archaeologists Pete Fowler & Ian Blackwell (1998) described the carving as “a cluster of several round depressions…each about two inches across”; though incorrectly ascribed it as the “southernmost example” of cup-marked stones outside of Cornwall.¹ Another rock-art student known as Mr Hobson, following his excursion to the site with the regional authority Pete Glastonbury, wrote:

“The cups themselves are very smoothed out, and fit the bill from the drawing. The horseshoe is very evident, as is the ‘slug’ mark, possibly a half-finished groove from one of the cups near the horseshoe. There are also some angular, yet serpentine (?) grooves at turf level on the south side of the stone. These look like they might be enhanced natural marks in places.”

The rock itself isn’t in its original position, having been moved from another point very close by (probably only yards away). It is sited on the edge of an old boundary line — which made me wonder whether the ‘U’- or ‘C’-shaped ingredient in the carving was a later addition, perhaps of one of the old land-owners hereabouts. The cups however, seem typical of the thousands that we find in northern Britain.

The isolation of this carving is rather anomalous. Others should be in the area but archaeo-records are silent (though the majority of Wessex archaeologists are academically illiterate when it comes to identifying such carvings). The carving may simply be the product of nomadic northerners, showing what their tribes do ‘up North’, so to speak. However, considering the tough nature of southern sarsen stones, it’d have taken ages to etch just this one stone. You can visualise it quite easily: southern tribal folk looking on, somewhat perplexed, as a northern traveller tried to convey what they etch on their stones in the northern lands, only to struggle like hell with cup-marks they’d do with ease on the softer rocks of their homelands. Wessex tribes-folk may have watched, seen the trouble their traveller had over such inane and (perhaps) meaningless carvings, and didn’t see the mythic point s/he was trying to convey…

Or maybe not!

The lesson with rock-art tends to be simple: where there’s one carving, others are nearby. The rule aint 100% of course — but when we were here the other day I was wanting to dart here, there and everywhere to check the many thousands of outcrop rocks that scatter this entire area. Us rock-art nuts tend to do things like that. It’s a madness that afflicts…

There were one or two stones with ‘possible’ single cup-markings on them, but I wasn’t going to start adding them to any catalogues. They were far too questionable. I was wanting something a bit more decent than that. And then, when Mikki, June, Pete, Geoff and I got to the collapsed long barrow known as the Devil’s Den a few hundred yards further down this rock-strewn sea of a valley, there was something with a bit more potential that we came across…

Folklore

In recent years this cup-marked stone has already attracted imaginative notions, with little foundation. Archaeologists Fowler & Blackwell (1998), in their otherwise fine book, think this carving was related to goddess worship, describing how,

“On Dillion Down…the Great Mother’s help was permanently invoked by patiently indenting a special stone with symbols of her potency.”

Adding that this “was a new idea brought in from the North, and Fyfield was the only place to have such a stone.” Weird! I could’ve sworn there were plenty of other rocks between here and there!

References:

- Fowler, Peter J., Landscape Plotted and Pieced: Landscape History and Local Archaeology in Fyfield and Overton, Society of Antiquaries London 2000.

- Fowler, Peter & Blackwell, Ian, The Landscape of Lettice Sweetapple, Tempus: Stroud 1998.

- Lacaille, A.D., ‘A Cup-Marked Sarsen near Marlborough, Wiltshire,’ in Archaeological Newsletter 7:6, 1962.

- Lacaille, A.D., ‘Three Grinding Stones,’ in Antiquity Journal, volume 43, 1963.

¹ Along with the cup-markings atop of Devil’s Den a few hundred yards to the south, across in Somerset we had the Pool Farm example; there are a number of examples in Dorset, including the Badbury Rings carving; plus others in Devon, etc.

* Pete Glastonbury is a Wiltshire-based photographer specialising in Landscapes, Astronomy, Archaeology, Infra-Red, Experimental Digital Photography and High Dynamic Range Panoramic photography.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.