Dun: OS Grid Reference – NM 8000 0763

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

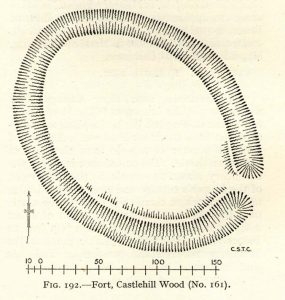

Up above the roadside leading down the gorgeous Craobh Haven road, we not only find remains of a previously unrecorded standing stone, but we see this little-known overgrown fort that has been described as a “galleried dun” by the Royal Commission (1988) lads. Known in folk tradition as the “castle of the black dogs” and an important place in the great legends of the Finns, in archaeological terms the Royal Commission described the site as:

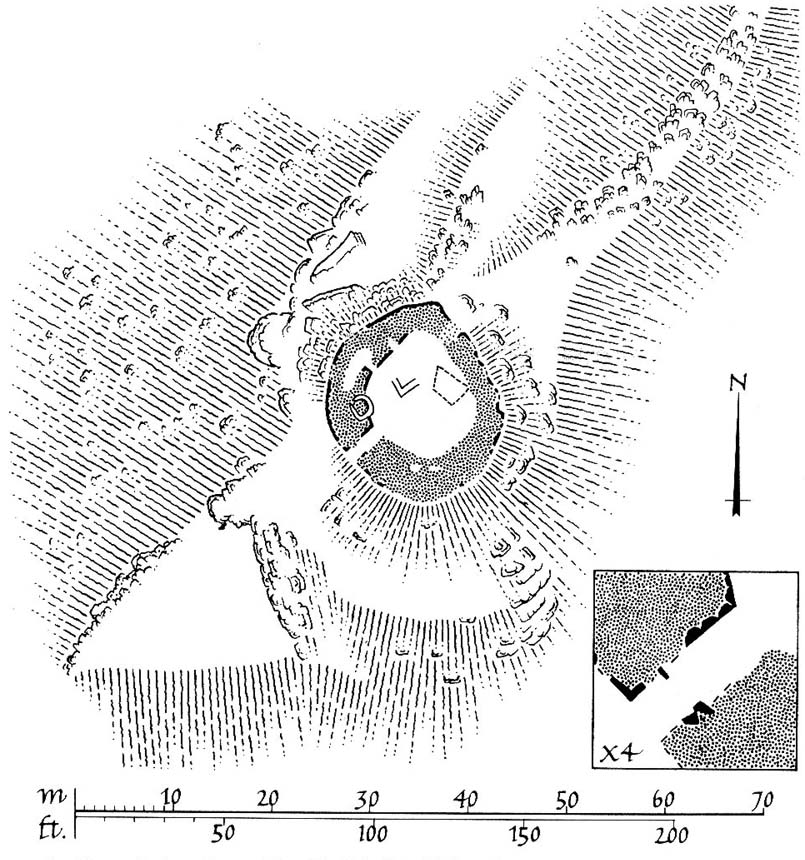

“Oval in plan, the dun measures about 13m by 10m within a wall which varies from 3m to 4m in thickness. Considerable stretches of the outer face survive and on the N it rises to a height of 1.7m in ten rough courses; the inner face is less well preserved, but a long stretch is visible on the NW. There are traces of a gallery within the thickness of the wall on the NW; it was entered through a narrow passage, the S-side wall of which it stands to a height of 0.4m in three courses. A second break in the line of the inner face, 2.5m to the NE, is either another entrance to the gallery or the entrance to a second chamber. Depressions in the thickness of the wall on the S may indicate the presence of yet another intramural feature. The entrance to the dun lies on the WSW; it measures about 1m in width at the outer end, 1.8m at the inner end, and is checked for a door 1m from the exterior. On the NE there is a short stretch of facing at right-angles to the line of the wall, and this may be a straight-joint similar to that at Castle Dounie…or one side of a postern gate. In the interior there are the remains of at least two animal-pens and a modern rectilinear cairn. There is no trace of the midden-deposit noted by Campbell & Sandemann to the W of the dun, and the cairns and stretches of field-walling on the N flank of the ridge are of relatively recent date.”

Folklore

Close to a little-known cailleach site, this ruined fortress was one of the many places which the illustrious historian and folklorist Archibald Campbell told about in his awesome series of Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition (1889). The tale of the fort was known to local people as “The Fight between Bran and Foir and is as follows:

“The black dog, Foir, was the brother of Bran, the far-famed hound of Fionn. Foir was taken early from his dam, and was afterwards nurtured by a band of fair women, who acted as his nurses. He grew up into a handsome hound, which had no equal, in the chase or in fight, in the distant North. His owner, Eubhan Oisein, the black-haired, red-cheeked, fair-skinned young Prince of Innis Torc (Orkney ?) was proud, as well he might be, of his unrivalled hound. Having no further victories to win in the North, his master determined to try him against the strongest dogs in the packs of the Feinne.

“He left home, descended by Lochawe, and entered Craignish through Glen Doan. Before his arrival, the Fienne, after spending the day in the chase, encamped for the night in the upper end of Craignish. Next day Fionn arose before sunrise, and saw a young man, wrapped in a red mantle and leading a black dog, approaching towards him at a rapid pace. The stranger soon drew near, and at once declared his object in coming. He wanted a dog-fight, and so impatient was he to have it, and so restless by reason of his impatience, that he suffered not his shadow to dwell a moment on one spot.

“Fifty of the best hounds of the Feinne were slipped at last, but the black dog killed them all one by one. A second and then a third fifty were uncoupled, but the strange dog disposed of them as easily as he did of the first.

“Fionn now saw that all the dogs of the Feinne were in serious danger of being annihilated, and therefore he turned round and cast an angry look on his own great dog Bran. In a moment Bran’s hair stood on end, his eyes darted fire, and he leaped the full length of his golden chain in his eagerness for the fight. But something else besides the casting of an angry look was still to be done to rouse the fierce hound’s temper to its highest pitch.

“He was placed nose to nose with his rival, and then his golden chain was unclasped. The two hounds, brothers by blood, but now champions on opposite sides, at once closed in deadly fight; but for an adequate description of the struggle between them the reader must consult the bards. See the “Lay of the Black Dog”, in Islay’s Leabhar na Feinne, the McCallum’s Ancient Poetry, etc.

“The contest lasted from morning to evening, and victory remained, almost to the close, uncertain; but in the end Bran vanquished Foir, and, by killing the latter, amply revenged the death of the three fifties. The Feinne buried their own dogs, and the stranger, with a sore heart, laid his black hound in the narrow clay bed.

“This great dog-fight, so celebrated in Gaelic lore, is said to have been fought at Lergychony, in Craignish. It is further said that the place was called Learg-a-choinnimh, or the “Plateau of Meeting”, because it was there the two hounds met in fight. There are, of course, many other places in the Highlands which claim the honour of being the scene of this legendary contest.”

References:

- Campbell, Archibald, Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition – volume 1, David Nutt: London 1889.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – Volume 6: Mid-Argyll and Cowal, HMSO: Edinburgh 1988.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.