Broch: OS Grid Reference – NG 24162 46424

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 10832

Getting Here

Dun Osdale, by the roadside

From the A863 Dunvegan road, a mile south of the village turn onto the B884 road at Lonmore, making sure you veer right after a few hundred yards and head towards Glendale. About a mile along, on the left-hand side of the road, note the small rocky crag that begins to grow just above the roadside. At the end of this crag you’ll see a huge pile of rocks, seemingly tumbling down, just by a small T-junction to Uiginish. You can’t really miss it.

Archaeology & History

Listed as one of the duns, or fortified prehistoric structures in Skye by the old writer J.A. MacCulloch (1905), the rediscovery of this broch was, said A.A. MacGregor (1930), one that “became historical only within living memory.” I find that hard to believe! The Gaelic speakers hereby merely kept their tongues still when asked, as was common in days of olde—and it was a faerie abode….

Looking at the SW walling

Looking at the SE walls

Once you go through the gate below the broch, the large boggy area you have to circumnavigate is the overflow from an ancient well, known as Tobar na Maor, where Anne Ross said, “tradition that the stewards of three adjacent properties met there.” This well was covered by an ancient Pictish stone (now in Dunvegan Castle), which may originally have been associated with the broch just above it. When I visited the site with Aisha and Her clan, we passed the overgrown well and walked straight up to the broch.

Despite being ruinous it is still most impressive. The massive walling on its southwestern side is still intact in places; but you don’t get a real impression of the work that went into building these structures until you’re on top. The walls themselves are so thick and well-built that you puzzle over the energy required to build so massive a monument. And Scotland has masses of them!

Aisha in the broch

Small internal chamber

The site was surveyed briefly when the Ordnance Survey lads came here in 1877, subsequently highlighting it on the first OS-map of the area. But it didn’t receive any archaeocentric assessment until the Royal Commission (1928) lads explored the area some fifty years later. In their outstanding Inventory of the region they described Dun Osdale in considerable detail, although kept their description purely architectural in nature, betraying any real sense of meaning and history which local folk must have told them. They wrote:

“The outer face of the wall of the broch for a great part is reduced to the lower courses, but on the west-southwest a section still maintains a height of about 7 feet; on the south-side, although hidden by fallen stones, it is about 4 to 5 feet high, and on the northeast there is a very short section 3 feet in height. The stones are of considerable size and laid in regular courses. In the interior a mass of tumbled stone obscures the most of the inner face of the wall, but on the south and northwest it stands about 8 feet above the debris. The broch is circular with an internal diameter of 35 feet to 35 feet 6 inches, and the wall thickens from 10 feet on the north to 13 feet 7 inches on the south. The entrance, which is one the east, is badly broken down, but near the inside has a width of 3 feet 2 inches, and appears to have been 2 feet 10 inches on the outside; it has run straight through the wall without checks. In the thickness of the wall to the south of the entrance is an oval chamber measuring 10 feet long by 4 feet 9 inches broad above the debris with which it is half-filled. The roof has fallen in, but the internal corbelling of the walls is well displayed. The fallen stones no doubt still cover the entrance, which has probably been from the interior. Within the western arc of the wall, nearly opposite the main doorway, is another oval cell 12 feet in length and 4 feet 6 inches in breadth over debris, with a doorway 2 feet 9 inches wide; its outer and inner walls are 5 feet 9 inches, and 2 feet 6 inches respectively. The roof od this chamber has also collapsed, but from the masonry which remains in position it must have been over 6 feet in height. Immediately to the west of the cell near the entrance are exposed the left jamb of a door and a short length of a gallery 3 feet 6 inches wide in the thickness of the southern wall, which probably contained the stairs, as traces of a gallery at a higher level than the oval chambers are seen here, the inner wall being about 3 feet and the outer 8 feet thick. Parts of a scarcement 9 inches wide can be detected on the northwestern and southeastern arcs.”

Dun Osdale plan (RCAHMS 1928)

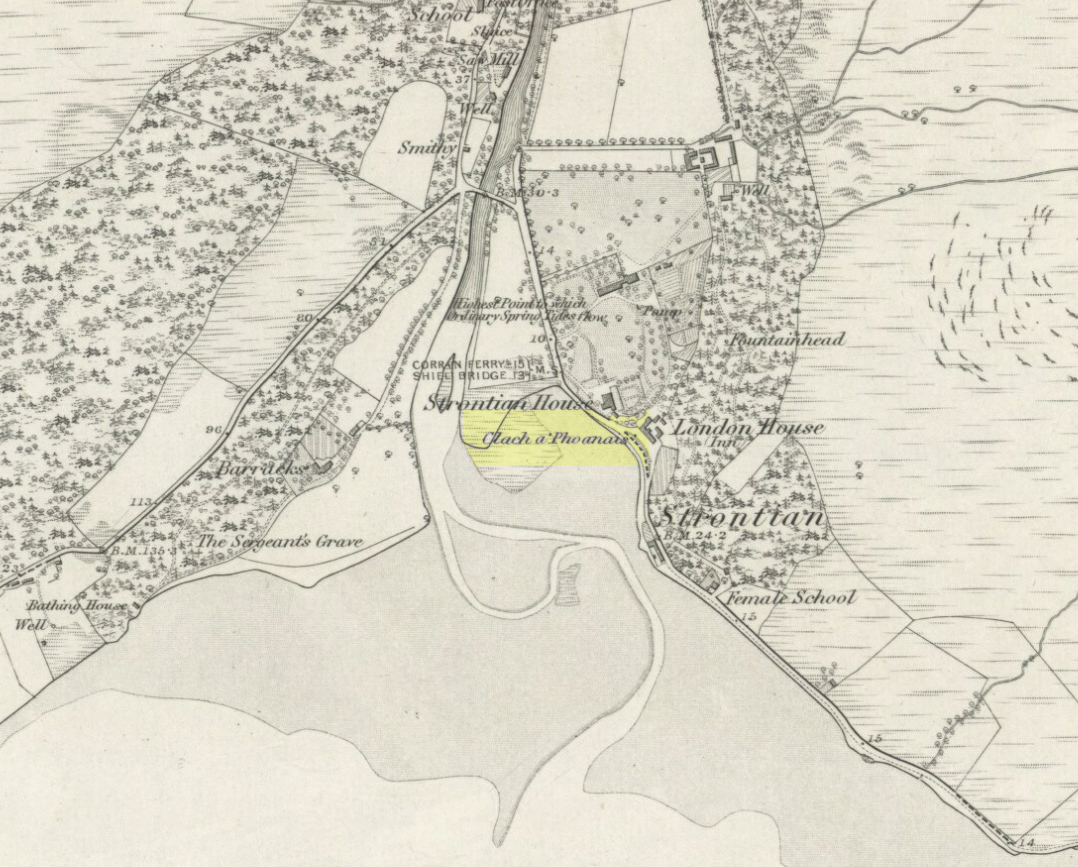

Dun Osdale on 1881 map

Measurements and architectural tedium aside, the broch is worthwhile for anyone interested in our ancient mythic past, not least because of its position in the landscape and its visual relationship with other sites of the same period nearby. As well as that, there are unrecorded ancient sites still hiding in these olde moors…

Folklore

Tradition tells that Dun Osdale was used as a watch-tower by the tribal folk—which seems quite credible. But the original inhabitants of Duirinish, the sith or fairy folk, were also said to live here. It’s one of several places in Duirinish where the legendary Fairy Cup of Dunvegan was said to have come from. Otta Swire (1961) told its tale:

“One midsummer night a MacLeod, searching for strayed cattle, stayed late on the moor. In the moonlight he saw the door of Dun Osdale open and the little people come out, a long train of them, and began to dance on the green grass knoll nearby. Fascinated, he watched, forgetting everything but the wonderful dance. Suddenly he sneezed. The spell was broke. The dance stopped. MacLeod sprang up to fly, but the fairies were upon him and he was dragged, willy-nilly, into the dun. Inside, as soon as his eyes grew accustomed to that strange green light associated with fairyland, he beheld a pleasing sight. A great banquet was spread on a large table carved from a single tree: on it were vessels of gold and silver, many of them set with jewels or chased in strange designs. His fairy ‘hosts’ led him to the table, poured wine into one of the beautiful cups and, giving it to him, invited him to toast their chief. Now this man’s mother was a witch, so he knew well that if he ate or drank in the dun he was in the Daoine Sithe’s power for ever. He lifted the cup and appeared to drink the required toast, but in fact skilfully let the wine run down inside his coat. As soon as his neighbours saw the cup was half empty, they ceased to bother about him but went off on their own affairs or to attend the banquet. Thereafter MacLeod watched for a chance of escape and, when one offered, slipped quietly through the door of the dun and away, carrying the cup with him.

“The fairies soon realised what had happened and started in pursuit, but he was already across the Osdale river and in safety. He hurried home, told his mother the story, and showed her the cup. Being a wise woman she realised the peril in which he undoubtedly stood and at once put her most powerful spell upon him to protect him from the arts of the Daoine Sithe, warning him seriously never to leave the house for a moment without getting the spell renewed. But she forgot to put a protecting spell upon the cup also. The fairies soon discovered the exact state of affairs and immediately laid their own spell upon the cup, a spell so powerful that all who saw the cup or even heard of it, were seized with an overmastering desire to possess it, even if such possession involved the murder of the holder.

“For a year, all went well and thanks to his mother’s care the young man went unharmed. Then he grew careless and one day ventured out without the protecting spell. A one-time friend, bewitched by the cup, had been awaiting just such a chance and immediately murdered him and went off with the prize. The fairies, their revenge achieved, took no further interest in the matter, but MacLeod of MacLeod did. The boy’s mother hurried to him with her story, and he at once gave orders that the murderer be found and brought to justice. He was duly hanged and the trouble-making cup, now free of enchantment, passed into the possession of the chief and can still be seen in (Dunvegan) castle.”

References:

- Donaldson-Blyth, Ian, In Search of Prehistoric Skye, Thistle: Insch 1995.

- MacCulloch, J.A., The Misty Isle of Skye, Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier: Edinburgh 1905.

- MacGregor, Alasdair Alpin, Over the Sea to Skye, Chambers: Edinburgh 1930.

- Royal Commission on Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the Outer Hebrides, Skye and the Small Isles, HMSO: Edinburgh 1928.

- Swire, Otta F., Skye: The Island its Legends, Blackie & Sons: Glasgow 1961.

Acknowledgements: Eternally grateful to the awesome Aisha Domleo and Her little clan for getting us to this ancient haven on Skye’s endless domain of natural beauty. Without Her, this would not have been written. Also, accreditation of early OS-map usage, reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.