Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 1194 5810

Getting Here

Take the A59 road from Harrogate and Skipton and at the very top of the moors keep your eyes peeled for the small Kex Ghyll Road on your left(it’s easy to miss, so be diligent!). It goes past some disused disused quarry and after a mile or so where you hit a junction, turn left, past the Outdoor Centre of West End and straight along Whit Moor Road. About a mile past the Outdoor Centre go left down to Brays Croft Farm and over the ford, then keeping to the footpath up to the right (west) and note the clump of trees on the moors above you to the west. That’s where you need to be.

Archaeology & History

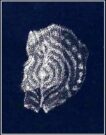

Several natural basins that might have been worked in prehistoric times are accompanied by several distinct cup-marks near the middle-edge of the stone, in a rough triangular formation, with two others slightly more eroded a little further down the same side. Boughey and Vickerman (2003) noted several other cupmarks on the rock, some distinct, some not so.

Adjacent to this carved stone is another naturally worn stone of some size, with incredibly curvaceous ripples over the top of the rock which, in all probability, possessed some animistic property to the people who carved this and other nearby carvings. Check the place out. It’s a gorgeous setting!

References:

- Armstrong, Edward A., The Folklore of Birds, Collins: London 1958.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian