Standing Stone: OS Grid References – NN 54058 20794

Also Known as:

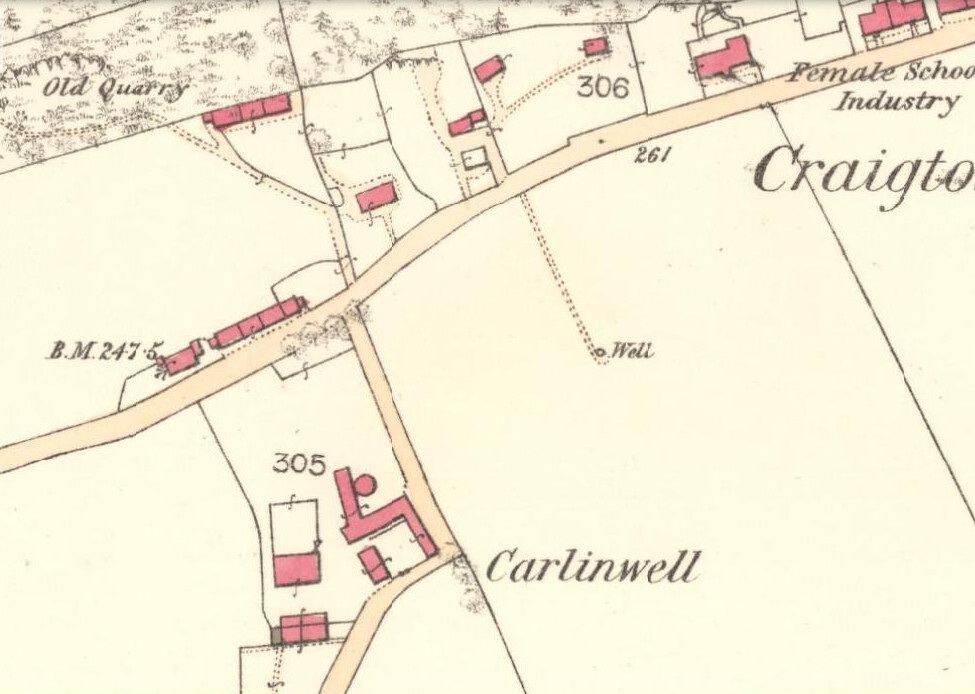

From Balquhidder village, take the road east towards Auchtubh as if you’re gonna visit the Priest’s Stone, just past the house of Tom na Cruich on the right-hand side of the road. When you get to the house, if you ask the owners there how best to get to the stone, they are very friendly and very helpful in pointing you in the right direction.

Archaeology & History

This solitary standing stone first seems to be mentioned in J.W. Gow’s (1887) essay on the prehistoric antiquities of this part of Rob Roy’s country. Found below the house and hillock where the old gallows used to be, he told:

“On the level ground below (Tom na Croich) …there is a prominent monolith, standing about 4½ feet above ground, quite flat, on the top. It is shaped like a wedge, with the edge to the east, and is famous in Balquhidder as the place where trials of strength took place.”

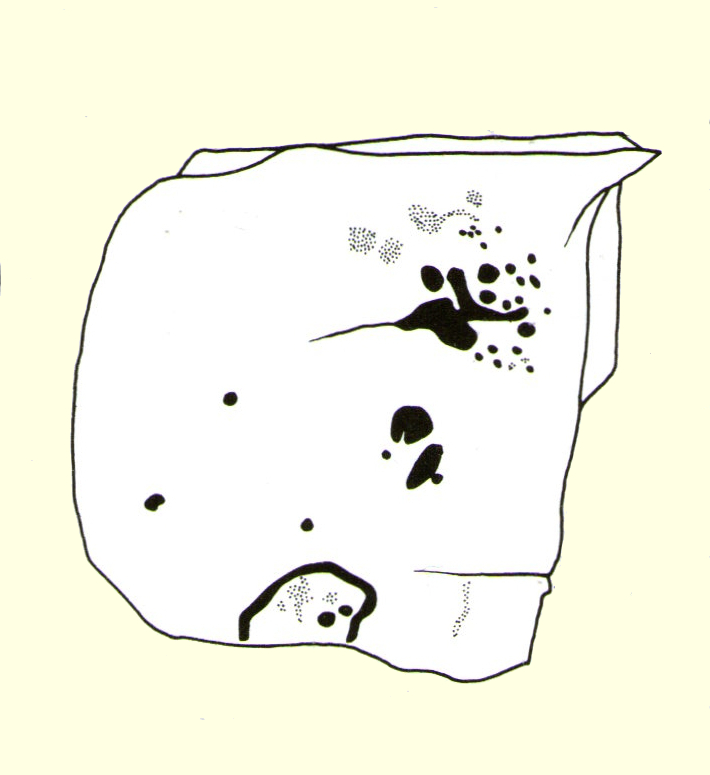

Below the standing stone is a small rock, whose predecessor played an important part in some local traditions relating to this site. (see ‘Folklore’ below) Also, due west of here in the next field, you will be able to see a couple of seemingly upright stones in the tall reeds 200 yards away, which early records say were part of a stone circle—now much in ruin—known as Clachan Aoraidh or the Worshipping Stones. There is the possibility that this single stone was an outlier to the circle. It’s astronomy might be worth checking….

Folklore

When we visited the stone last week, the owners of the house above asked if we’d managed “to lift the stone”—and I wondered what they meant at first, until they told us the folklore about the site. They narrated the tale almost exactly as it had been described first of all in J.W. Gow’s (1887) essay, which said the following:

“It is shaped like a wedge, with the edge to the east, and is famous in Balquhidder as the place where trials of strength took place. A large round water-worn boulder, named after the district, ‘Puderag’, and weighing between two and three hundredweight, was the testing stone, which had to be lifted and placed on the top of the standing stone. There used to be a step about 18 inches from the top, on the east side of the stone, on which the lifting stone rested in its progress to the top. This step or ledge was broken off about thirty years ago, as told to me by the person who actually did it, and the breadth of the stone was thereby reduced about 8 inches. This particular mode of developing and testing the strength of the young men of the district has now fallen into disuse, and the lifting-stone game is a thing of the past. A former minister of the parish pronounced it a dangerous pastime. Many persons were permanently injured by their efforts to raise the stone, and it is said that he caused it to be thrown into the river, but others said it was built into the manse dyke, where it still remains. There were similar stones at Monachyle, at Strathyre, and at Callander, and no doubt in every district round about, but the man who could lift ‘Puderag’ was a strong man and a champion.”

The present stone that is positioned on the ground below the standing stone was put here in much more recent times.

References:

- Gow, James M., “Notes in Balquhidder: Saint Angus, Curing Wells, Cup-Marked Stones, etc”, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 21, 1887.

Acknowledgements: To Kenny and Laura for their help and guidance here. Huge thanks!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian