Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NN 7080 2327

Also Known as:

1. Well of St. Fillans

Archaeology & History

Found by the legendary hill of Dundurn, east of Loch Earn, this legendary healing site has been written about by many historians, both local and national. An early account of it was given by the local priest, Rev. Mr McDiarmid, minister of the parish of Comrie at the end of the 18th century, who informed those compiling the Old Statistical Account of the area, the following information:

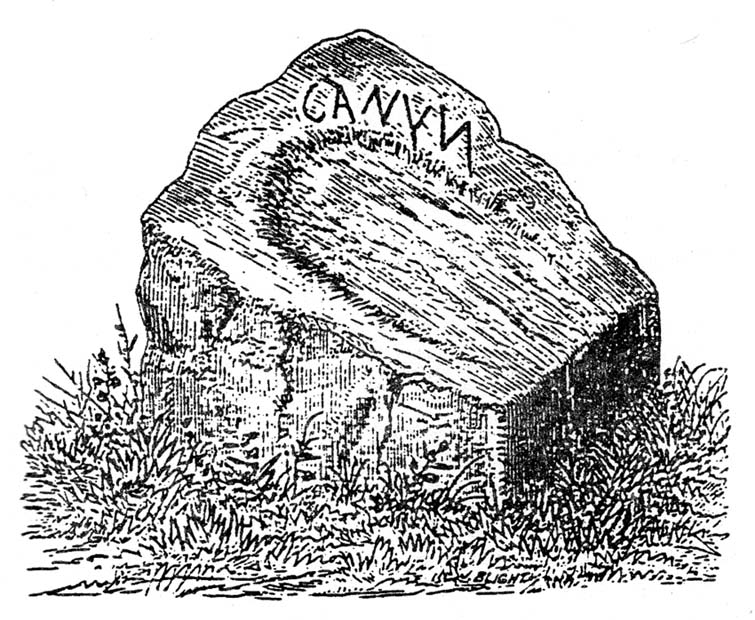

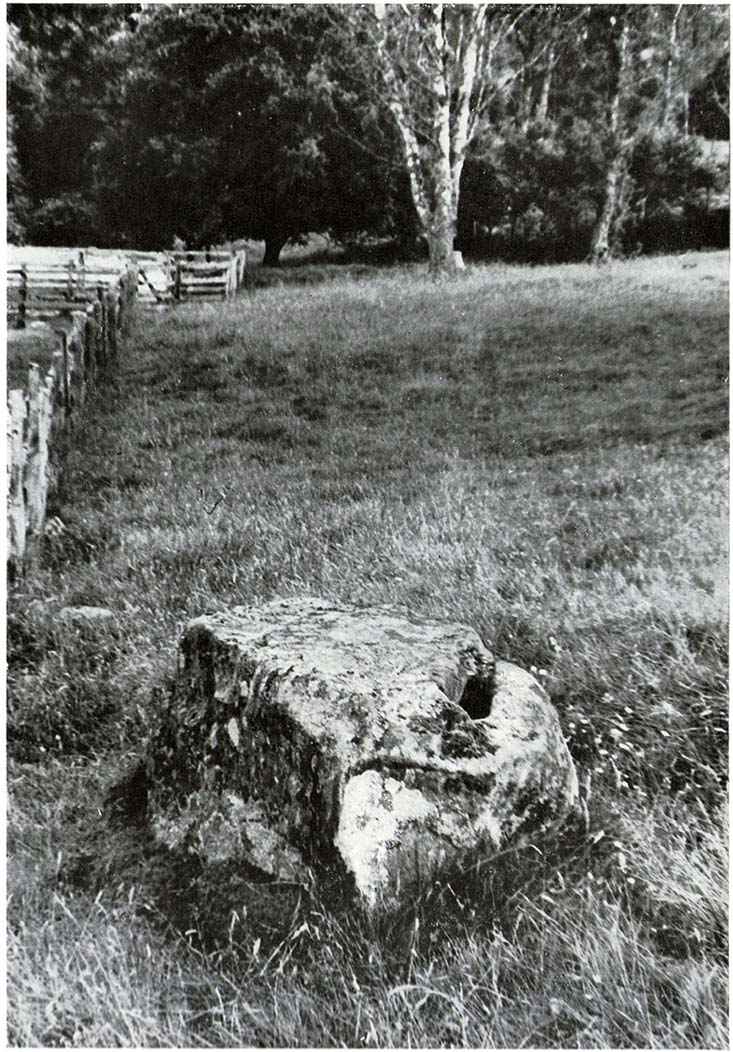

“This spring, tradition reports, reared its head on the top of Dun Fholain (Fillan’s Hill) for a long time, doing much good, but in disgust (probably at the Reformation) it removed suddenly to the foot of a rock, a quarter of a mile to the southward, where it still remains, humbled, but not forsaken. It is still visited by valetudinary people, especially on the 1st of May and the 1st of August. No fewer than seventy persons visited it in May and August, 1791. The invalids, whether men, women, or children, walk or are carried round the well three times in a direction Deishal—that is from east to west, according to the course of the sun. They also drink of the water and bathe in it. These operations are accounted a certain remedy for various diseases. They are particularly efficacious for curing barrenness, on which account it is frequently visited by those who are very desirous of offspring. All the invalids throw a white stone on the Saint’s cairn, and leave behind them as tokens of their gratitude and confidence some rags of linen or woollen cloth. The rock on the summit of the hill formed of itself a chair for the Saint, which still remains. Those who complain of rheumatism in the back must ascend the hill, sit in this chair, then lie down on their back, and be pulled down by the legs to the bottom of the hill. This operation is still performed, and reckoned very efficacious. At the foot of the hill there is a basin made by the Saint on the top of a large stone, which seldom wants water even in the greatest drought, and all who are distressed with sore eyes must wash them three times with this water.”

We see from this early account that there’s a discrepancy regarding the location of St. Fillan’s Well, as the modern accounts indicate it to be at the top of the craggy hill. In some upland regions this occurred so as to maintain a sense of secrecy about the location of local sites, so ensuring they were not affected or disturbed by outsiders or incomers, who not only disrespected local customs and rites, but tried changing or altering them to their new ways. It also kept the local gods and spirits of the sites protected from tourism and the profane. This may explain the difference in locations described by Rev. McDiarmid.

About one hundred years after McDiarmid’s account, another priest called Tom Armstrong (1896) wrote a piece in the Chronicles of Strathearn (1896) all about this holy well, saying:

“People are prone to believe that the dirty pool of stagnant water which still remains in the driest summer on the top of St. Fillan’s Hill is the famous spring to which pilgrims at one time resorted. Any one who examines it will not fail to observe that it has all the appearance of an artificially built well, and must have been kept in order and preservation for a purpose. Tradition confirms the belief that this was at one time the well, but not always.”

The hill on which it is found was an ancient dun or fort, built in prehistoric times, making you wonder how far back in time its magickal abilities were known about.

…to be continued…

References:

- Armstrong, Thomas, “By the Well of St. Fillan,” in Chronicles of Strathearn (David Phillips: Crieff 1896).

- Gordon, Seton, Highways and Byways in the Central Highlands, MacMillan: London 1948.

- Hunter, John, et al, Chronicles of Strathearn, David Phillips: Crieff 1896.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.