Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – NT 1486 8466

Archaeology & History

This little-known iron-bearing spring takes some finding! It’s all but lost beneath a mass of invasive rhododendrons that cover the slopes here (it needs to be severely cut back) and will only be found by the truly adventurous amongst you. In notes of this site by Ordnance Survey in 1854, they told that “there was formerly a fountain to protect the Spring, but the fountain has been allowed to go to ruin” and I could see no remnants here on my visit.

In a detailed and lengthy analysis of the spring water that was done by W. Robertson in 1829, the principal minerals in it were found to be iron, magnesia and lime, but the spring was said to have no medicinal renown locally.

References:

- Robertson, W., “Analysis of the Water of a Spring on the Estate of Fordel near Inverkeithing,” in Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal (ed. Robert Jameson), volume 14, 1829.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

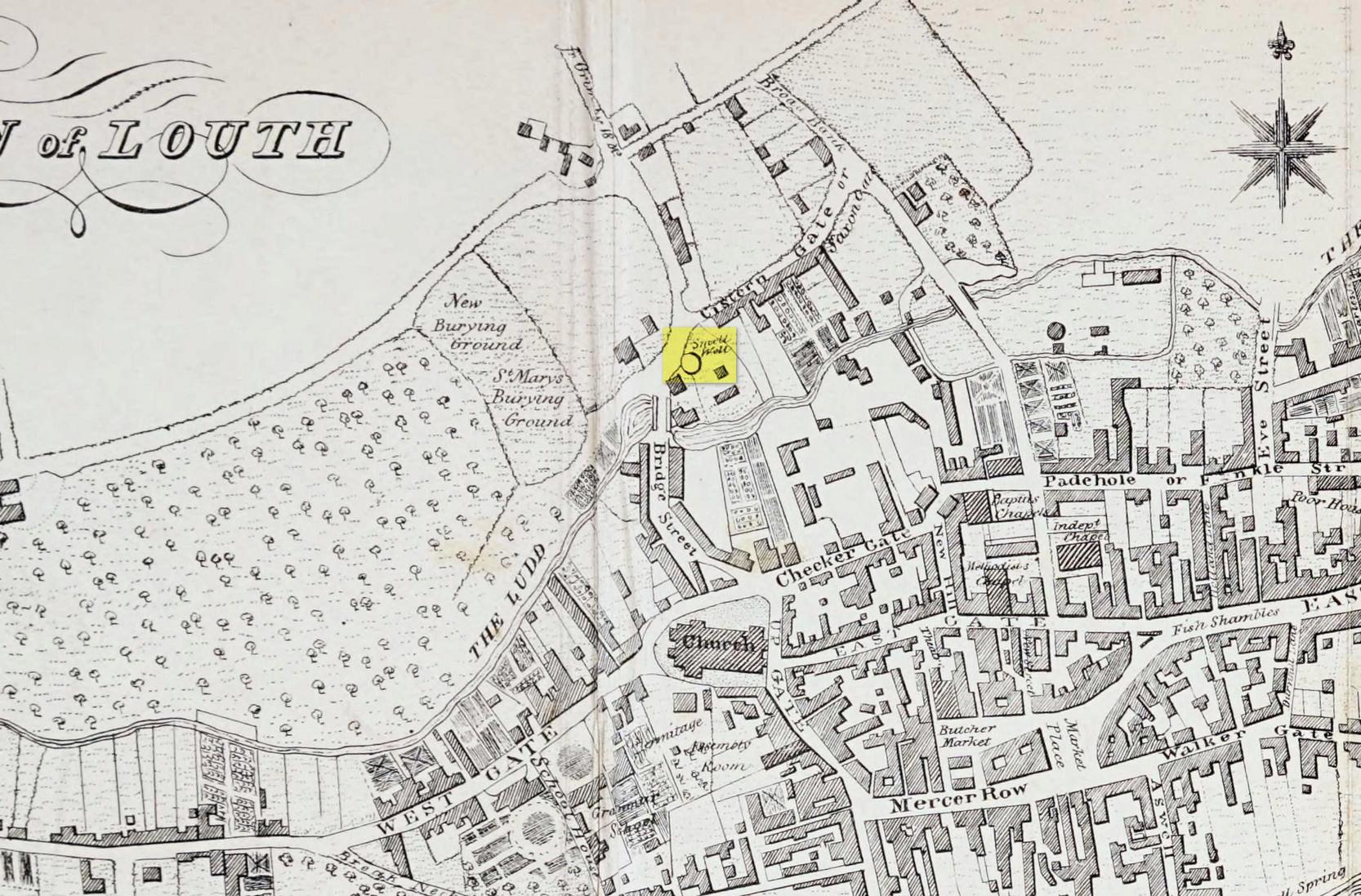

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.