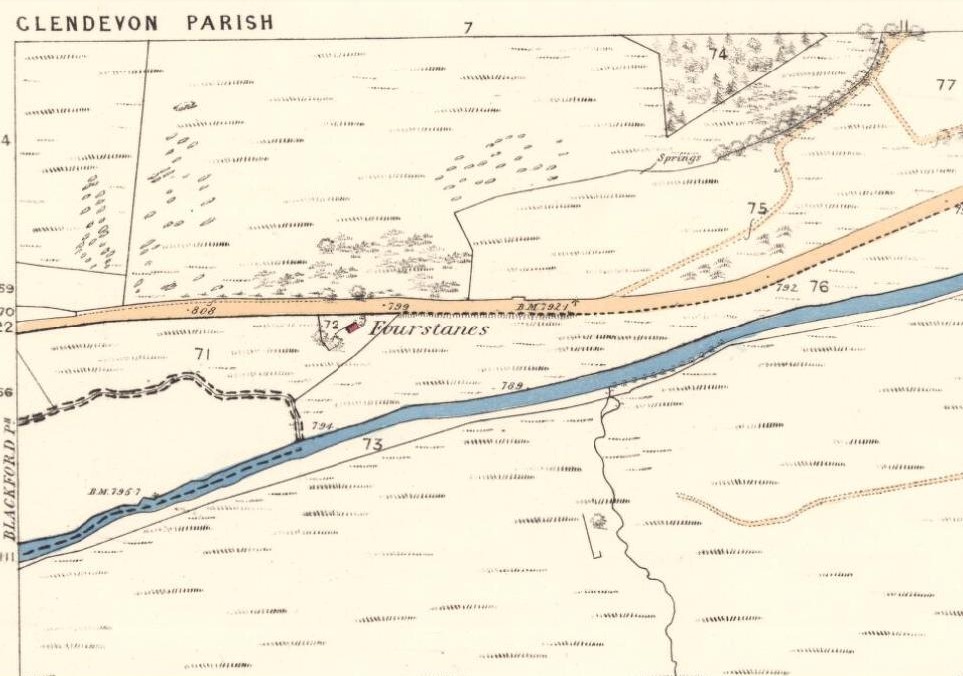

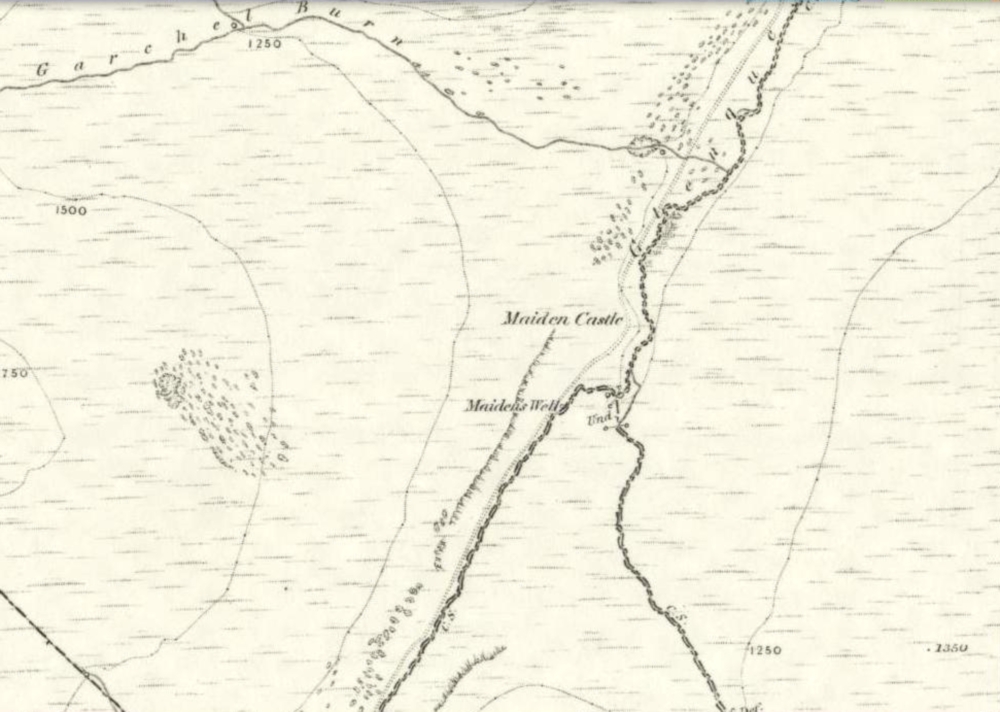

Hillfort: OS Grid Reference – NO 0008 0365

Also Known as:

- Castle Hill

- Dun Hill

Getting Here

Travelling north along the A823 Glendevon road (between Muckhart and Gleneagles), barely 2 miles after Muckhart, on your right you’ll see the large Castlehill reservoir. Park here. Across the waters is the large Down Hill—which the hillfort crowns. So, just walk back the way you came along the road for nearly 600 yards and then turn left to walk onto the other side of the water, round to the very end of the track and then up the path into the trees. Walk along this winding path for 300 yards until you reach the track that takes you (left) up to Downhill Farm. One way or the other, past there, just stagger up to the top of the hill!

Archaeology & History

My only visit here was a short one – when some pretty awesome freezing gales were nearly throwing me off the top once I’d got up there! Twas incredible! On my way to the top, nearly there, on its western side, I stopped and looked each side of me as it looked as if a long overgrown line of embankments was running roughly north-south. It seemed very vague and hillforts aren’t my subject, so with the help of the wind throwing me everywhere, I made my my final zoom to the summit, only to be intruded upon again, perhaps 50 feet from the top by another similar-looking embanked ridge—this time with some stones along it and which I was pretty sure were earthworks, or ramparts as they’re known. And so it turned out to be.

Once on top, the views are superb! But I couldn’t really take it in on my short visit here as the freezing wind was truly incredible and I could barely stand upright. And so I briskly followed to the quite notable stone-walled edges of the main prehistoric “enclosure” and walked round the edges as best I could, hoping that at least one or two of the photos I was taking weren’t too blurred.

The interal “settlement” portion of the hillfort is quite large, obviously, allowing for a good number of people to live here (regardless of the wind!). It’s roughly oblong in shape, aligning northwest to southeast, measuring in length a maximum of 78 yards from outer wall to outer wall, with a maximum width of 30 yards (SW to NE). The collapsed walling is still quite extensive and visible above the long grasses almost all the way round the entire structure, averaging one or two yards across. Near the centre of the fortress is a large pile of stones that seemed to have been a structure of some kind, but when i was here I didn’t hang around for too long to inspect it as I was, by now, bloody freezing! It didn’t seem to be a walker’s cairn, but we need another gander to work out what it might have been.

Curiously this site has had little said about it in archaeo-tomes and to my knowledge, no excavations have happened here. Incredibly, the place wasn’t even recognised as a prehistoric site in official records until the Royal Commission (1963) told of it being “discovered during the survey of marginal lands (1956-58)”! Its very name derives from the word dun, or fort (Watson 1995) and as the place-name writer found out, it was first mentioned in 1542, as Donehill, and many times thereafter in various documents.

Anyhow—check the place out. It’s mightily impressive and the views from the top are excellent. Just avoiding going up there in a freezing gale!

References:

- Hogg, A.H.A., British Hill-Forts: An Index, BAR: Oxford 1979.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirlingshire – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

- Watson, Angus, The Ochils: Placenames, History, Tradition, PKDC: Perth 1995.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.