Rocking Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 37363 61280

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

On the outer southern edge of Kilbarchan parish—right near the ancient boundary line itself—this giant stone of the druids is seems to be well-known by local folk. Located about 40 yards away from the sacred ‘St Bride’s Burn’ (her ‘Well’ is several hundred yards to the west), it was known to have been a rocking stone in early traditions, but as Glaswegian antiquarian Frank Mercer told us, “the stone no longer moves.” The creation myths underscoring its existence, as Robert Mackenzie (1902) told us, say

“This remarkable stone, thought by some to have been set up by the druids, and by others to have been carried hither by a glacier, is now believed to be the top of a buried lava cone rising through lavas of different kind.”

The site was highlighted on the first OS-map of the area in 1857, but the earliest mention of it seems to be as far back as 1204 CE, where it was named as Clochrodric and variants on that title several times in the 13th century. It was suggested by the old place-name student, Sir H. Maxwell, to derive from ‘the Stone of Ryderch’, who was the ruler of Strathclyde in the 6th century. He may be right.

Folklore

Folklore told that this stone was not only the place where the druids held office and dispensed justice, but that it was also the burial-place of the Strathclyde King, Ryderch Hael.

References:

- Campsie, Alison, “Scotland’s Mysterious Rocking Stones,” in The Scotsman, 17 August, 2017.

- MacKenzie, Robert D., Kilbarchan: A Parish History, Alexander Gardner: Paisley 1902.

Acknowledgements: Big thanks to Frank Mercer for use of his photos and catalytic inception for this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Little Almscliffe, Stainburn, North Yorkshire

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 23242 52260

Also Known as:

- Little Almes Cliffe

- Little Almias Cliff Crag

Archaeology & History

The crags of Little Almscliffe are today peppered with many modern carvings, such as are found on many of our northern rock outcrops. Yet upon its vertical eastern face is a much more ancient petroglyph – and one that seems to have been rediscovered in the middle of the 20th century. When the great northern antiquarian William Grainge (1871) visited and wrote of this place, he told us that, “the top of the main rock bears…rock basins and channels, which point it out as having been a cairn or fire-station in the Druidic days; there are also two pyramidal rocks with indented and fluted summits on the western side of the large rock” – but he said nothing of any prehistoric carvings. Curiously , neither the great historian Harry Speight or Edmund Bogg saw anything here either.

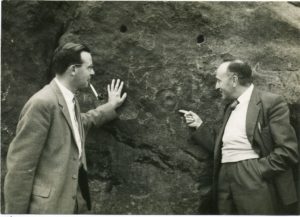

This singular cup-and-ring design seems to have been reported first in E.S. Wood’s (1952) lengthy essay on the prehistory of Nidderdale. It was visited subsequently by the lads from Bradford’s Cartwight Hall Archaeology Group a few years later; and in the old photo here (right) you can see our northern petroglyph explorer Stuart Feather (with the pipe) and Joe Davis looking at the design. In more recent times, Boughey & Vickerman (2003) added it in their survey of, telling briefly as usual:

“On sheltered E face of main crag above a cut-out hollow like a doorway is a cup with a ring; the top surface of the rock is very weathered and may have had carvings, including a cupless ring.”

Indeed… although the carving is to the left-side of the large hollow and not above it. Scattered across the topmost sections of the Little Almscliffe themselves are a number of weather-worn cups and bowls, some of which may have authentic Bronze age pedigree, but the erosion has taken its toll on them and it’s difficult to say with any certainty these days. But it’s important to remember that even Nature’s ‘bowls’ on rocks was deemed to have importance in traditional cultures: the most common motif being that rain-water gathered in them possessed curative properties.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Bogg, Edmund, From Eden Vale to the Plains of York, James Miles: Leeds 1895.

- Bogg, Edmund, Higher Wharfeland, James Miles: Leeds 1904

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Grainge, William, History & Topography of Harrogate and the Forest of Knaresborough, J.R. Smith: London 1871.

- Parkinson, Thomas, Lays and Leaves of the Forest, Kent & Co.: London 1882.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to James Elkington for use of his fine photos on this site.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Maen Sigl, Llandudno, Caernarvonshire

Legendary Stone: OS Grid Reference – SH 7792 8297

Also Known as:

- Rocking Stone

- St. Rudno’s Stone

Archaeology & History

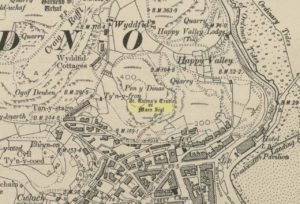

Highlighted on the 1901 OS-map of the area, this old rocking stone was located on the heights of Pen y Filas above Llandudno. Originally a site of heathen worship—the druids, it is said—the site was later patronised by the Irish saint, Tudno: a hermit who lived in a cave (Ogof Llech) a mile to the northwest, on the heights of the legend-filled Great Orme.

Rocking stones are well-known as geo-oracular forms (stone oracles) in folklore texts across the country, although they’re almost entirely rejected by historians as little more than ‘curiousities’ and meaningless geological formations. In olde cultures elsewhere in the world however, stones like this were always held in reverence by traditional people – much as they would have done in Wales and elsewhere in Britain.

References:

- Hughes, Arthur R., The Great Orme: Its History and Traditions, R.E. Jones: Conway n.d. (c. 1950)

- Jones, H. Clayton, “Welsh Place-Names in Llandudno and District” in Mountain Skylines and Place-Names in Llandudno and District, Modern Etchings: Llandudno n.d. (c.1950)

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Samson’s Stone, Crieff, Perthshire

Legendary Rock: OS Grid Reference – NN 82519 22021

Also Known as:

Tale the A85 road between Comrie and Crieff and, roughly halfway between the two towns, take the minor road south to Strowan (it’s easily missed, so be aware!). A few hundred yards along, stop where the trees begin and walk into the fields immediately east. Keep walking, below the line of the trees, and you’ll get to it within five minutes.

Archaeology & History

Mistakenly cited by some as a standing stone, the large boulder which rests here on the hillside just below the woodland is a glacial erratic. Highlighted on the 1866 OS-map of the region, I hoped that we might find some rock art on the stone, but cup-and-rings there were none. However, there is a curious ‘footprint’ on top of it, similar to the ones found at Dunnad, at Murlaganmore and other places (see Bord 2004); but I can find no previous reference to this carved footprint.

In 1863 the site was described in the local Name Book, where it was reported to be “a large oblong shaped stone lying on the surface, eight feet long, four wide, and three thick”; but, much like today, it was also reported that “There is no tradition respecting it in the neighbourhood. Supposed to have received the name in consequence of its great size.”

Most peculiar…..

References:

- Bord, Janet, Footprints in Stone, Heart of Albion Press 2004.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Heatheryhaugh, Bendochy, Perthshire

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NO 19639 51153

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 29141

- Mains of Creuchie

Take the A93 road north out of Blairgowrie for 5 miles or so to the Bridge of Cally, making sure you do NOT drive up the A924. Keep on the A93 for a coupla hundred yards, just as you come out of the village take the right turn on the minor road to Drimmie. When you hit the dead straight section of road, turn left near its end. The follow this bendy moorland road for 1½ miles (2½km) where a small copse of trees appears on the nearby hillock on your left. In the next field past this, close to the roadside, you’ll see a large boulder.

Archaeology & History

A large rock in the large field 350 yards (320m) SSE of the lovely Park Neuk stone circle which was described by the Royal Commission (1990) lads as being a “cup-and-ring” stone is, sadly, not as impressive as it sounds. The carving was initially rediscovered and described by Mrs Lye (1982) who told:

“A large glacial erratic boulder with ten cup marks scattered over its surface lies in a field one sixth of a mile SSE of the ‘four poster’ and ruined stone circle at Heatheryhaugh. The boulder is garnet mica schist and is 3m long, NS, by 2.70 wide, EW, with a circumference of 9m at ground level.”

When the Royal Commission visited the carving in 1987 they found that it had,

“on its sloping W face at least fifteen weathered cupmarks, two cups with single rings and one cup with a possible ring; the cupmarks average 50mm in diameter by 15mm in depth.”

But some of these ‘cups’ are, without doubt, geological in origin – and when Paul Hornby and I visited the stone in near perfect weather conditions, there was only one ring very faintly discernible, with a possible arc on the top-edge of another ‘cup’. You can see from a couple of the photos how some of the cupmarks are geophysical in nature. The cups with greater veracity were very probably etched from the natural cut in the stone (as found at Stag Cottage and many other cup-and-rings).

References:

- Lye, Mrs D., “Heatheryhaugh: Cupmarked Stone,” in Discovery & Excavation in Scotland, 1982.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, North-East Perth: An Archaeological Landscape, HMSO: Edinburgh 1990.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Kirk Stones, Morton Moor, West Yorkshire

Legendary Rocks (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 0886 4479

Archaeology & History

A place-name that is still recognised on modern Ordnance Survey maps, even though the original site giving rise to it was all but destroyed some one hundred-and-fifty years ago. Derived from the old word kirk, meaning a church or sacred site, no christian remains of any kind have ever existed here and so we must presume an earlier, more heathen site of sanctity (an abundance of prehistoric petroglyphs exist very close by). The singular reference detailing the nature of these Kirk Stones is in J.A. Busfield’s (1875) rare tract on the history of Upwood, in the parish of Bingley. Upwood Hall was built by the Busfield family and, as the author tells,

“one of the most striking features in the vicinity at this age [c.1800, PB] was the fine range of magnificent rocks called Kirkstones, which had existed for countless ages. These grand rocks, towering one above another, extended along the whole southern boundary of the [Whetstone] Allotment on the left of the road to Ilkley, and were really a fine object, but alas!, through the ignorance or stupidity of the agent Colonel Bence, the “Crags of Kirkstone” were broken up and disposed of in the construction of the Bradford Water Works about the year 1854.”

Sadly we have neither illustrations nor other references to these fine sounding sentinels.

Undoubtedly the Kirkstones were a natural feature, despite their venerated title. It would have been their very appearance that gave rise to their revered title, as in the great and contorted rock masses seen at Brimham Rocks which, from Bensons’s description, these Kirk Stones seem reminiscent. The only piece of extant lore to these stones is that the uprights that went into making the recently destroyed Bradup stone circle a short distance south of here, came from this sacred outcrop. It seems reasonable to assume that they played an important role in the magickal history of these hills when they were scattered with forest.

The Kirk Stones aligned along the equinox axis to the Black Knoll standing stone less than a mile [1.4km] due east.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Busfield, Johnson Atkinson, Fragments Relating to a History of Bingley Parish, Bradford 1875.

- Smith, A.H., English Place-Name Elements – Part 2, Cambridge University Press 1956.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Ringstone, Torrisdale Bay, Farr, Sutherland

Legendary Rock: OS Grid Reference – NC 69128 61741

Along the A836 road between Tongue and Bettyhill, turn down towards Skerray at Borgie Bridge for 1.8 miles (2.87km) until you reach the little information sign at the roadside. Walk downhill and cross the little bridge and wander onto the west side of the beach. You’re likely to end up daydreaming… so once you’ve re-focussed, head into the middle of the beach and walk up the steep-ish sand-banks to your right (south). Once at the top, you’ll see a gigantic rock—the Ringstone—bigger than a house.

Folklore

This gigantic boulder is part of one of Sutherland’s archaic Creation Myths as they’re known: ancient stories recounted by archaic societies about the nature and origins of the world. Such tales tend to be peopled by giants, gods, huge supernatural creatures, borne of chaos, eggs, darkness and primal oceans. Thankfully we still find some examples of these tales in the northern and northwestern mountainous regions of Britain, as the Church and Industrialism never quite destroyed the hardcore communities—despite what they might like to tell you…

The following folktale of the Ringstone was thankfully preserved by the local school headmaster, Alan Temperley (1977), before it vanished orever from the oral traditions of local people (as is sadly happening in these mountains). It typifies stories told of such geological giants from aboriginal Australia, to Skye, to everywhere that people have lived. Mr Temperley wrote:

“Many years ago there were two giants, the Naver giant from the river at Bettyhill, and the Aird giant from the hill above Skerray. Normally they got on quite well, but one afternoon they became involved in a heated argument about some sheep and cattle, and both grew very angry. The Aird giant was standing on top of the hill above Torrisdale bay with the animals grazing around him, and the Naver giant stormed across the river to the beach below.

“Those are my sheep,” he roared up the hill.

“No they’re not,” the Aird giant said. “At least not all of them.”

“You stole them. You’re a thief!”

“No I didn’t. They came up here themselves. Anyway, you owe me fifty sheep from last year.”

“You’re not only as thief, you’re a liar!” shouted the Naver giant. If you don’t send them down this minute, I’ll come up and see to it myself.”

At this the Aird giant gave a disparaging laugh and made a rude face, and picking up a great boulder flung it down the hill at his friend.

The Naver giant was speechless with fury, and picking the stone up himself, hurled it back up the hillside, making a great hole in the ground.

The Aird giant saw things had gone far enough.

“I’ll send them back if you give me that silver ring you’re always wearing,” he said.

“Never!” roared his friend, his face all red and angry.

“Suit yourself then,” said the Aird giant, and picking the stone up again he tossed it back down the hill.

For long enough the rock kept flying between them, and in time the giant from Naver grew tired, because he was throwing it uphill all the time.

“Will you give me the ring now?” said the Aird giant.

For answer the Naver giant tried one more time to throw the stone up the hill, but it only got halfway, and rolled back down to the shore.

“Come on,” said the giant from Aird, for he wanted to be friends again. “Give me the ring, and I’ll let you have it back later.”

“No!” said the Naver giant from the bottom of the hill. “I’ll never give it to you!” His eyes began to fill with tears.

“Oh, come on, please!” coaxed the Aird giant. “Just for a week.”

“Never, never, never!” shouted the giant from Naver, and pulling the ring from his finger he threw it on the ground and jammed the great boulder down on top of it. Then he sat down on top of the stone and stared out to sea. Every so often he sniffed, and his friend, looking down at his broad back, saw him lift the back of a hand to his eyes.

They never made friends again, and after a long time they both died.

The ring is still buried under the stone, and so far nobody has ever been able to shift it.”

When I got back from visiting this immense rock a few weeks ago, a local lady Donna Murray asked me if I’d seen the face of the giant in the rock. I hadn’t—as I was looking to see if the name ‘Ringstone’ related to any possible cup-and-rings on its surface, which it didn’t (although I didn’t clamber onto the top). But in the many photos I took from all angles, Donna pointed out the blatant simulacra of the giant’s face when looking at it from the east.

However, on top of the slope above the Ringstone (not the Aird side), I did find a faint but distinct ‘Ringstone’ carving (without a central cupmark). Whether this ever had any mythic relationship to the tale or the stone, we might never know. The rocky terrain above Aird now needs to be looked at…

References:

- Eliade, Mircea, Patterns in Comparative Religion, Sheed & Ward: London 1958.

- Long, Charles H., “Cosmogony,” in Eliade, M., Encyclopedia of Religion – volume 4, MacMillan: New York 1987.

- MacLagan, David, Creation Myths: Man’s Introduction to the World, Thames & Hudson: London 1977.

- Temperley, Alan, Tales of the North Coast, Research Publishing Company: London 1977.

Acknowledgments: Massive thanks again to Donna Murray, for her help and for putting up with me amidst my wanderings up in Torrisdale and district.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian 2017

Leckie Broch Carving (02), Gargunnock, Stirlingshire

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 6926 9399

Take the A811 road between Stirling and Kippen and go up into Gargunnock, From the village centre, go along the Leckie Road (not the Main Street!) for half-a-mile, then turn left up the tiny road. ¾-mile (1.15km) along, a small bridge crosses the Leckie Burn (a.k.a. St Colm’s Burn). From here, walk up the footpath into the woods for 100 yards or so and cross the waters. When you see the large overgrown rocky rise of the Leckie Broch covered in pesky rhododendrons, walk up its left-side where (presently) a clearing has been made and the carved rocks stand out.

Archaeology & History

A very curious design here! Possibly carved at the same time as the Leckie broch to which it is attached—possibly not—we have here a curious amalgam of Nature’s incisions and human design, culminating in cup-and-rings and cups-and-squares no less! When we came to visit it a few days ago, Lisa Samsonowicz found the stone hiding away, buried beneath a thin layer of natural cover. The rest of the team thereafter enabled a much clearer pictures of the carving.

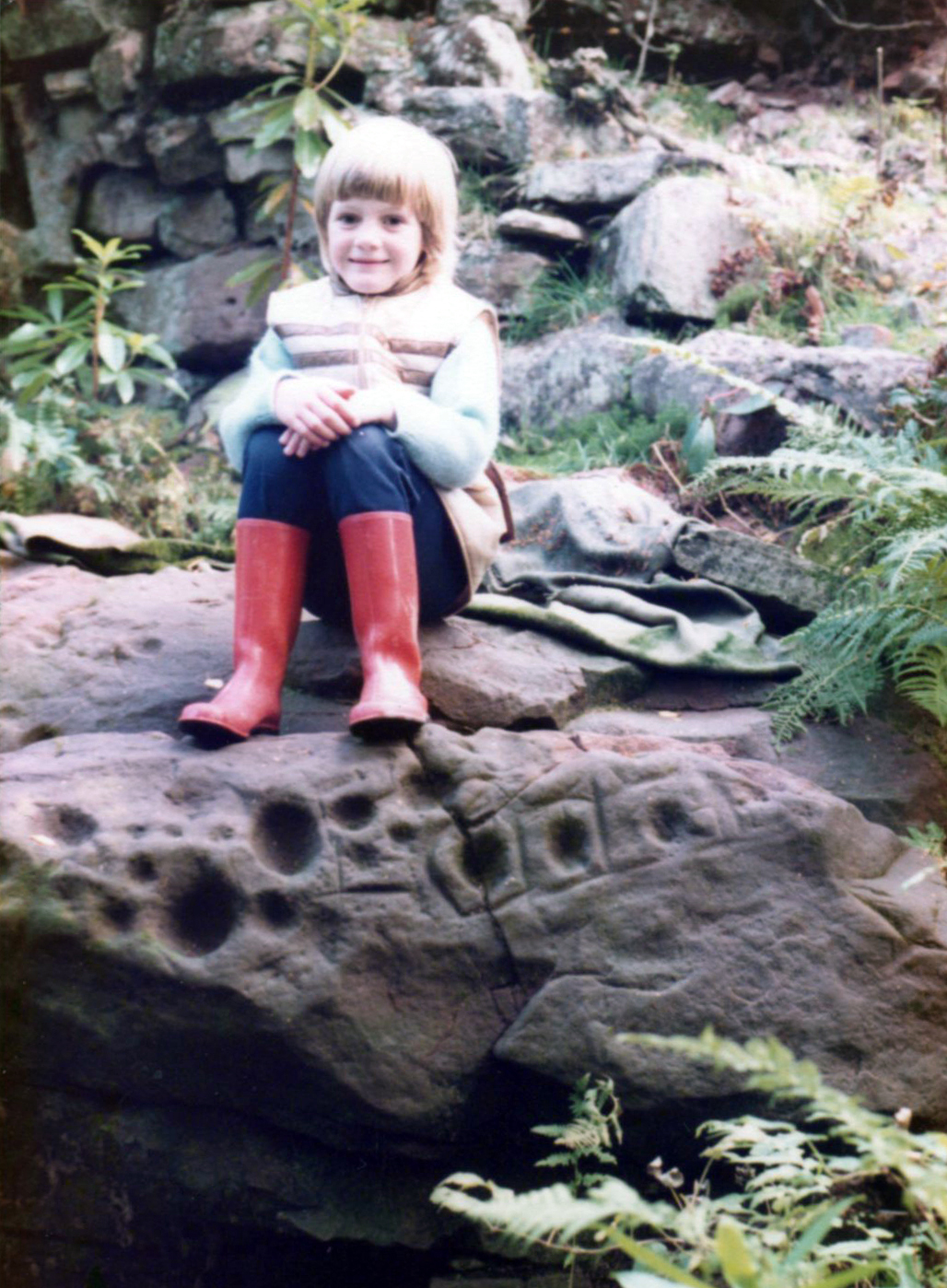

We’re not quite sure who first rediscovered the carving. In an early photo of the site taken in the late ’70s or early ’80s, a young Allison McLaren sits highlighting the design. But she wasn’t the fortunate lass who discovered it! One account describes a local woman, Lady Younger of Leckie House, who was out walking her dog, accidentally dislodging some of the rocky debris of the Iron Age broch and unearthing the petroglyphs, thereafter taking Allison along to see it. The other account tells of it being noticed for the first time during an excavation of the broch by Euan MacKie and his team. Whichever it was, Prof Mackie (1970) was certainly the first person to write about it. He told:

“Part of the sandstone face of the northern end of the promontory on which stands the Leckie dun is covered with well preserved cup-marks, presumably much older than the dun. They were discovered when rubble and soil fallen from the dun was removed. Some of the cup-marks stand alone and some are surrounded by what appear to be incised rectangles in a ladder pattern. There are other, less clear markings.”

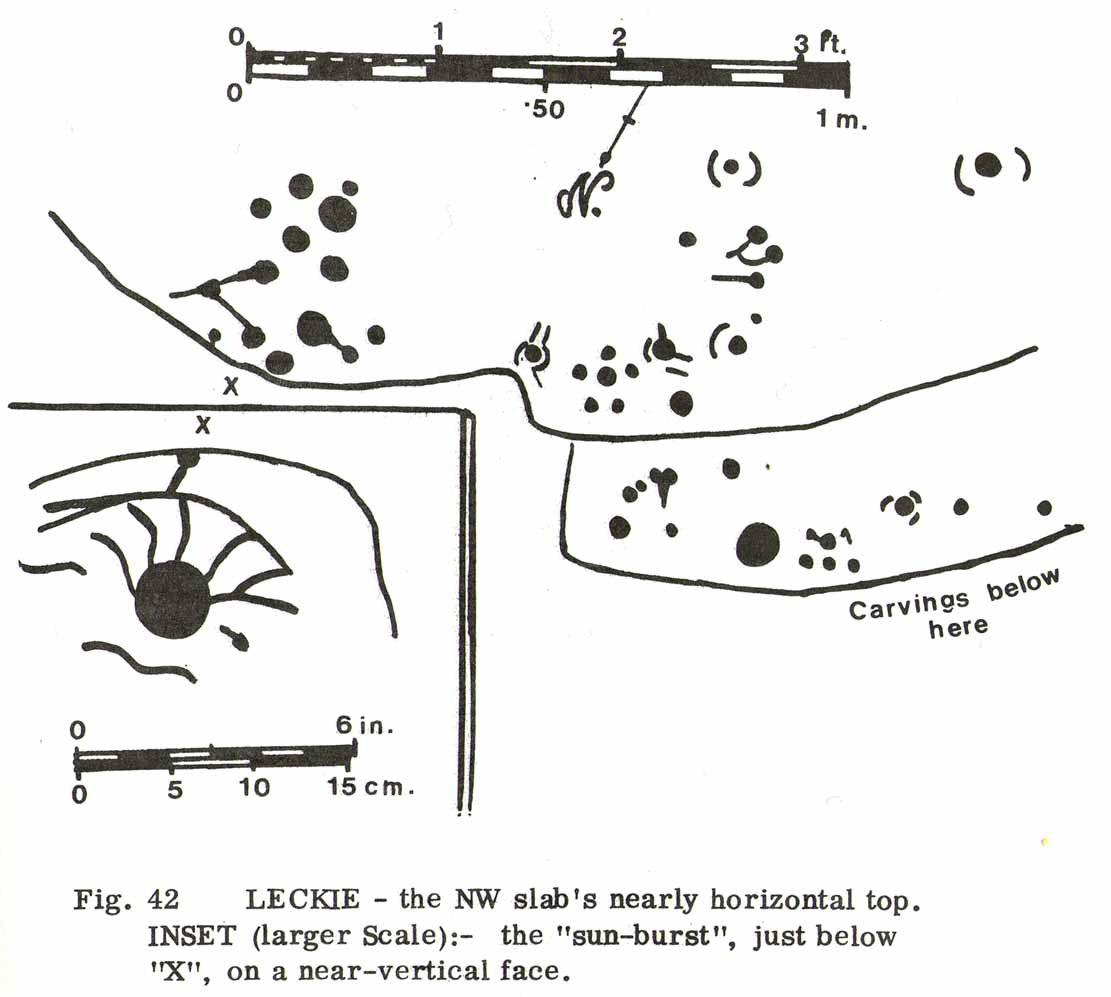

There then followed a series of written accounts, small and large, about the Leckie broch—but little else was said of the carvings. It wasn’t until Ronald Morris (1981) came to see them a few years later that they gained a slightly lengthier description. He described how the petroglyph was,

“carved over about 3m (yds) at heights of 1-2m (yds) on faces now sloping mostly 0-90º NW, with 3 cups-and-one-near-hexagonal-ring up to 12cm (4½in) diameter, a ‘sun-burst’ and other grooves, and at least 40 cups up to 12cm (4½in) diameter and up to 8cm (3in) deep. On a vertical E-facing slab there are also many grooves, some of which connect lines of cups. Some grooves resemble a ‘sea-horse’, an ‘axe’, etc. All except the cups are probably incised, but some may be natural.”

The entire design in fact covers two separate sections of rock. On the vertical face of one stone is a curious conjoined cup-and-rectangle, attached to a cup-and-square, attached to a traditional cup-and-ring. A cluster of other cups, large and small, are immediately left of this odd geometric pattern. The ‘cups’ within this section of the petroglyph are quite deep and, it would seem, were geological in nature but have been touched-up by human hands. Immediately below this rectangle-square-circle sequence, faint carved lines run a little further down the face of the rock. They were difficult to see clearly and require subsequent visits to enable a more complete picture. Along the top of this section of rock are several cups, one or two of them seeming to have faint rings around them. (at the very bottom of this vertical carved face, at ground level, a small section of man-made walling is visible, which was no doubt a section of the huge broch)

Above the top of this vertical carved face is a gap between this and a second, larger earthfast stone. This has a series of cups, some with faint rings around them, but most of them are just cups, both shallow and deep, running down the slope of the rock. A notable ‘star’ of five cups surrounding a single-cup stands out on this section. Some of them seem to have been geophysical in nature, but again have been touched-up and added to.

Slightly higher still, on another third section of rock, a curious cluster of weird ‘pecks’, almost in a square pattern, with a possible cup-mark close to the edge of the stone is clearly visible. The edge of this rock seems to have been quarried and the markings here may just be mason marks preceding the breaking of the stone in the Iron Age.

Walk around to the south-side of the broch and there, in the walling, on a vertical stone face, is the small cup-marked Leckie 1 carving.

One final note of concern: the carving (and the broch) have become overrun with rhododendrons, to the point where they are severely damaging the monuments here. They need to be curtailed before further archaeological destruction occurs. Help!

References:

- MacKie, Euan, “Leckie, Cup-Marked Rock,” in Discovery & Excavation Scotland, 1980.

- MacKie, Euan, “The Leckie Broch, Stirlingshire,”, in Glasgow Archaeological Journal, volume 9, 1982.

- McLaren, John, Personal Communications, 7.2.17 & 16.2.17.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

Links:

Acknowledgements: Immense thanks to Lisa Samsonowicz, Fraser Harrick, Nina Harris, Frank Mercer and Paul Hornby for all their work, enabling a clear picture of the site. And a huge thanks to John McLaren of the Gargunnock Village History site for allowing us to include the early photo of the carving here – thanks John! 🙂

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Ballochraggan 05, Port of Menteith, Perthshire

Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 56044 01549

Also Known as:

- Ballochraggan 42 (Brouwer)

- Canmore ID 78355

- Menteith 5 (van Hoek)

Take the same directions as if you’re visiting the Ballochraggan 12 carving, or nearby standing stone. Literally 10 yards above the leaning monolith, you’ll see what looks like a glacial rock drop ahead of you (though it’s actually volcanic). That’s the stone you want!

Archaeology & History

A site that was first described in Maarten von Hoek’s (1989) survey of the area, where he told this carving to be “a loose boulder (that) bears 14 cups, some possibly natural.” There is very little doubt about it—many of the ‘cups’ on this stone are indeed natural, caused directly by the erosion and subsequent falling of conglomerate rock nodules coming away from the larger rock mass, leaving holes in it that look like cup-marks, but are blatantly natural in origin.

When Paul Hornby and I visited the site on August 28, 2014, we looked briefly at the stone and then walked on by—but we took some photos, “just in case the archaeo’s have this listed as a monument, ” I said. And they do! Several of the ‘cups’ shown in the images here might be man-made. Might…. It’s difficult to say for sure (are there any geologists in the house?) Of course, if the faint half-ring below one of these large ‘cups’ turns out to be legitimate, we’ve got a definite here. But even that looks a bit dodgy!

Despite these marks possibly being geophysical, we must not forget, nor rule out, that this rock had some importance to the neolithic or Bronze Age people who frequented this region. Natural marks on rock would be emulated by humans sometimes, or seen as elements of spirit in the stone itself—as found all over the world. A standing stone is only yards away, and we have highly impressive multiple cup-and-ring stones very close by. The natural ‘cups’ on this and other adjacent rocks may have catalysed the petroglyphs themselves.

Check it out when you visit the other, much more impressive multiple-ringed carvings hereby; but also watch out for the many conglomerate rocks still scattering this hill—some with the softer rounded nodules of rock fallen, leaving cups, and others still in place in quite a few of the stones, awaiting their own geological timing to leave more cup-marks ready for some folk to misread. (I did it misself in younger years!)

References:

- Brouwer, Jan & van Veen, Gus, Rock Art in the Menteith Hills, BRAC 2009.

- van Hoek, M.A.M.,”Prehistoric Rock Art of Menteith, Central Scotland,” in Forth Naturalist & Historian, volume 15, 1992.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Split Stone, Bridge of Allan, Stirlingshire

Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 81116 99311

Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 81116 99311

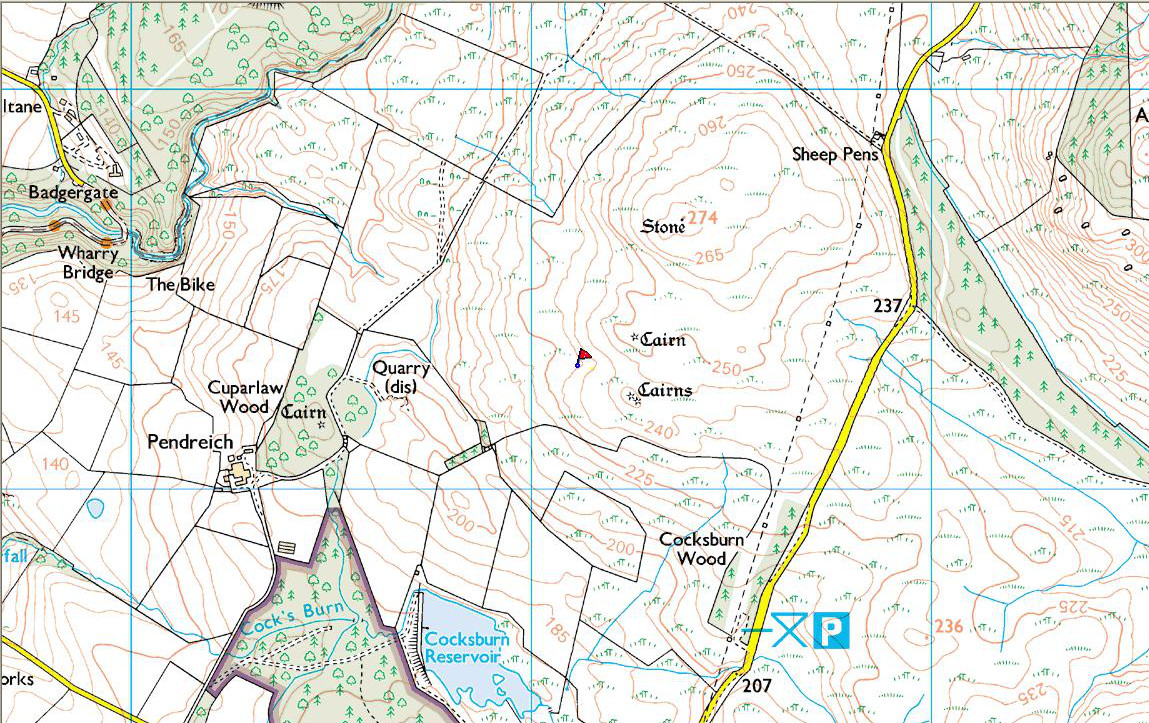

Take the same directions as if you’re gonna find the Pendreich Moor cairn up the hills behind and north of Stirling University (there are 2 very close to each other). Once upon the cairned hill, walk dead straight WNW for 100 yards or so, or down the slope into the small valley, then westwards. You’ll hit an overgrown length of very old walling. Keep walking along here and, below it, you’ll find these stones laying down in the shallow grasses on the south-side of the all-but dried stream. The large Cuparlaw Wood cairn is 0.4 miles west of here.

Archaeology & History

This is something of an anomaly. There is no previous written history about the place (that I can find) and archaeologists and historians on The Prehistoric Society and CBA forums can offer no other explanation when asked: is this a standing stone that, many centuries ago, was cut and prepared to be erected, but never made it into the intended monument? (wherever that might have been) And so, I offer it onto TNA and ask the same of any readers, geologists or archaeo’s who might have an explanation for this curious, large split piece of stone, that lays silently on the western moorland edges of the Ochils, asking the same question.

When I first came across this site I was simply perplexed as to the why’s and wherefore’s of who had cut such a large rock into approximate halves. I must have walked around it many times, puzzling what the purpose would have been of doing such a thing, and how long ago the ‘split’ had been performed. About a year later I ventured up again and, when leaving to head back into Stirling, found no resolution to my puzzlement. It had me truly stumped!

It wasn’t until I visited the prehistoric Witches’ Stone about 15 miles away near Monzie Castle last year, that one of those ‘eureka!’ events occurred. The last thing on my mind was the curious split rock above Bridge of Allan. Fellow antiquarian Paul Hornby and I were taking photos of the Witches’ Stone, when one of us remarked how unusually flat and smooth one face of this upright standing stone was – in fact, incredibly flat and smooth – and that’s when it hit me! As I walked round and round the Witches’ Stone, the similarity between this upright example and the one laid on the ground about 15 miles away got stronger and stronger.

A week or two later, archaeology student Lisa Samson and I went back to the Split Stone to have another look at it. Without doubt, the appearance and size and type of rock were one and the same. The only real difference between the Witches Stone and this Split Stone on the edge of Pendreich Moor, is that one stands upright and the other is laid down.

As you can see from the photos, we have a large rock, 5-6 feet long, which was, at some time many centuries ago, split almost straight down the middle, following a natural line of weakness or mineral deposit running through the stone. In all probability this was a standing stone prepared and ready to be used in some neolithic or Bronze Age monument not too far way—but for some reason it never made the journey to its intended spot.

The age of this split rock needs assessing correctly by geologists. Walking around the earthfast halves, it is difficult to see any recent evidence of mason marks that might help us determine when the rock was cut like this. In looking at erosion marks on cut-and-dressed quarried stone from post-medieval periods, we find no equivalent scars on this Split Stone. There is what may be faint evidence of some cuts into the stone at the top and side, but these are very debatable; and very probably it seems that the stone must have been cut a very long time ago, thousands of years back, in order to erode all obvious mason marks. But it would be good to get a geologist to have a look and confirm or deny such things.

…And, as if this isn’t a mystery unto itself: walk across the dried stream and go up the slope right in front of you immediately north. There’s a small, almost level ridge you’ll reach after 30 yards up, before the hill then rises further. If you notice, in the grasses and heather around you, there’s much more of the overgrown ‘walling’ here along this ridge—and some of it, with dips here and there and about three feet tall in places, is in a circle! It’s man-made, it’s a ring of stones, you can see it on GoogleEarth pretty clearly, and it’s not in any official record books.

Watch this space!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian