Legendary Rock: OS Grid Reference – SE 12075 44833

Also Known as:

- Carving no.111 (Hedges)

- Carving no.115 (Boughey & Vickerman)

- Druid’s Chair

- Etching Stone

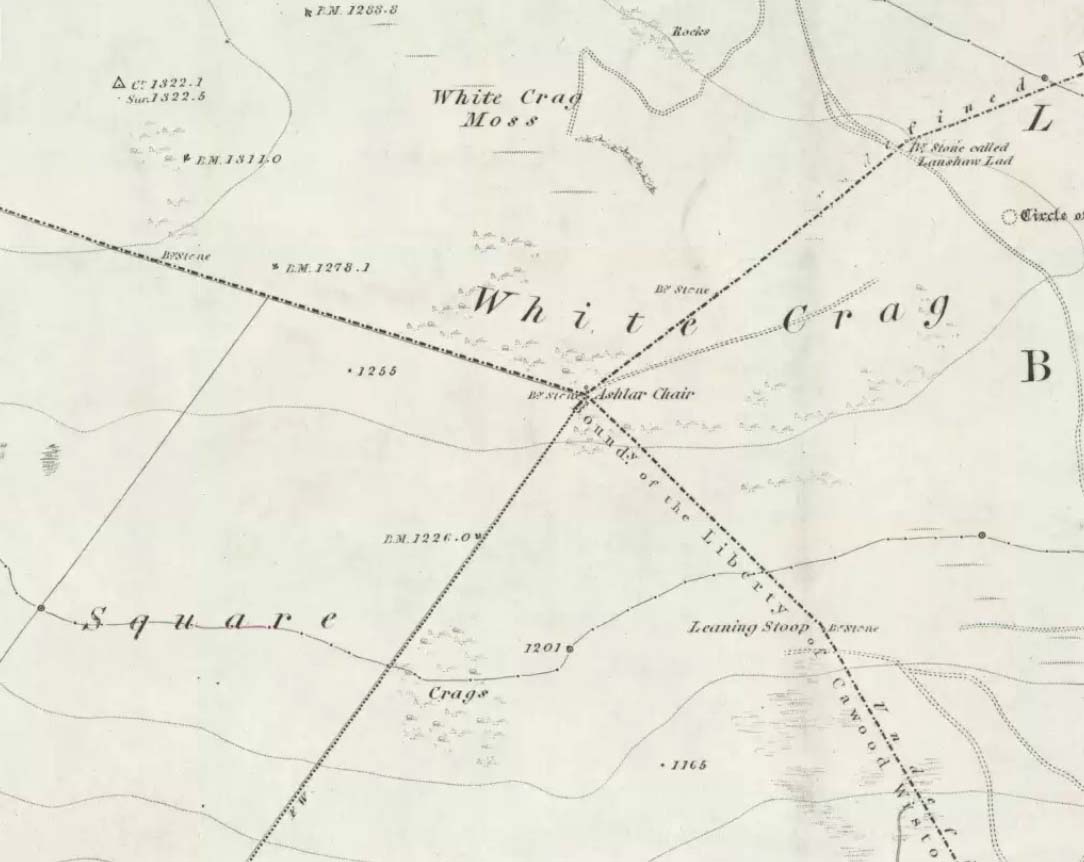

There are two large boulders here, one of which was deemed the Ashlar many moons back. You can approach it from the lazy way: park y’ car at the top of the road by the Whetstone Gate TV masts and walk east right along the boundary path till you get here. The better way is from Twelve Apostles: from there walk a coupla hundred yards north to the Lanshaw Lad boundary stone, where a small path heads west. Along here for another coupla hundred yards, then hit the footpath south for the roughly the same distance again. You’ve arrived!

Archaeology & History

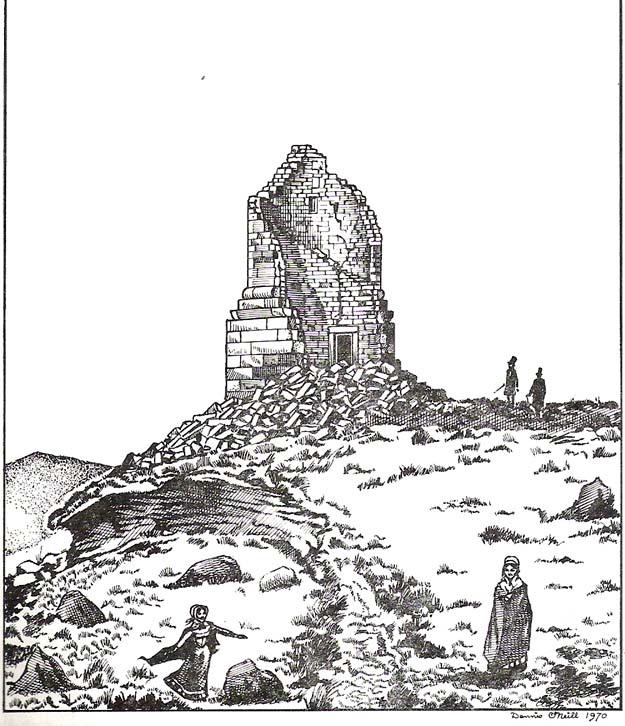

The Ashlar Chair is ascribed in folklore, said Harry Speight (1892), “to be a relic of druidism,” as one of its titles in ages past was the Druid’s Chair. In the nineteenth century it also became known as the Etching Stone, (Smith 1961-63) but it has retained its present title for more than two hundred years. Shaped more like a couch than a chair, its present title—the Ashlar—is important in ritual Freemasonry, which has two aspects to it: the ‘rough’ and the ‘perfect’. The first represents the neophyte; the latter, the illumined one. Oaths are sworn on the ashlar, and laws are spoken from it. In its higher aspect it is representative of the spiritual maturity of evolved man.

Although there are no public records as to who gave the site its present name, the land which lays before it, The Square, is an even greater indicator that this rock was was considerably more than just a curious place-name, for the open moorland that is overseen from Ashlar Chair—The Square — is 396,000 square yards of flat open heathlands that have never been archaeologically explored. The Square is also one of the most important elements of Freemasonry: representing the manifest universe, its laws are spoken from the Ashlar. (Jones 1950)

Between the two of them, represented here in the landscape near the very tops of these moors, we have a form of late geomancy, although the names of our geomancers are nowhere to be found. It is obvious though, simply from the name of the land, that dramatic ritual of some form was enacted here. In recent times, ritual magickians from differing Orders have found the place most effective, as have wiccan folk and other pagans who have frequented it at the summer solstice. The possibility that some members of the Grand Lodge of ALL England (a legendary Masonic Order, said by the modern London masons not to have existed until the eighteenth century) gave this place its name is not unreasonable. Records show that in the fourteenth century at least one member of the Order, Sir Walter Hawksworth, frequented ritual circles on these moors; and another member of the same Lodge from the nearby Washburn valley was an ally to the Pendle and Washburn witches who, we know, met on these moors at Twelve Apostles stone circle and probably the Ashlar. But it proves nothing I suppose. (I tend to believe (not a necessarily healthy viewpoint) that the Grand Lodge did use the Ashlar as one of their moot points, along with the Pendle and Washburn witches.)

Its primary geomantic attribute is as an omphalos. Geographically the Ashlar Chair is the meeting-point of Bingley, Burley, Morton and Ilkley moors and, metaphorically speaking, when you stand here you are outside the confines of the four worlds yet still a purveyor of them.

Upon the large rock itself it are carved the faint initials, “MM, BTP, ISP and IG, 1826.” Several early records described cup-and-ring designs on the Ashlar: firstly in Forrest & Grainge’s (1868) archaeological tour; then in Collyer & Turner’s Ilkley (1885); and lastly by the great Yorkshire historian and topographer Harry Speight (1892, 1900), who said “it bears numerous cups and channels.” Although we can see some of these on top of the Ashlar, they are mainly Nature’s handiwork. It is possible that some man-made cup-and-rings once existed on the rock, but if so they have eroded over time.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Collyer, Robert & Turner, J.H., Ilkley Ancient & Modern, William Walker: Leeds 1885.

- Forrest, C. & Grainge, William, A Ramble on Rumbald’s Moor, among the Dwellings, Cairns and Circles of the Ancient Britons in the Summer of 1867 – Part 1, W.T. Lamb: Wakefield 1868.

- Jones, Bernard E., Freemason’s Guide and Compendium, Harrap: London 1950.

- Speight, Harry, Chronicles & Stories of Old Bingley and District, Elliott Stock: London 1892.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.