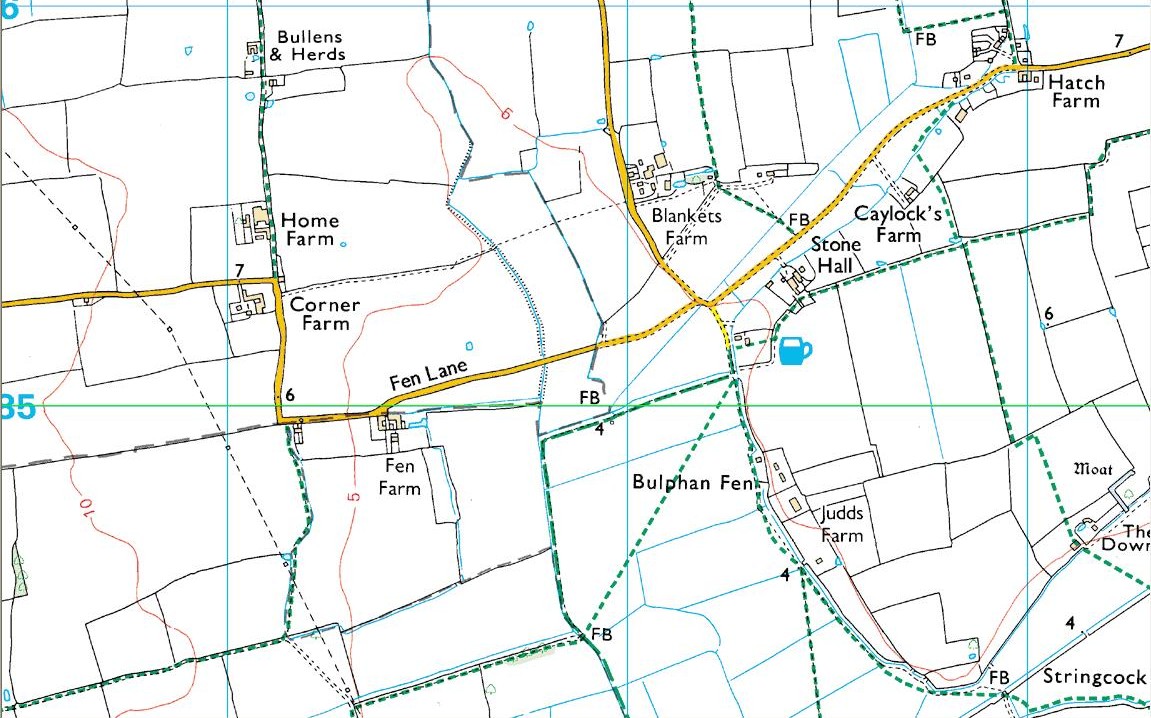

Holy Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – TQ 6538 7081

Also Known as:

- St. Thomas’ Well

- Shingle Well

Archaeology & History

Sadly the site is gone no longer in existence it was in the roadway along the Roman Watling Street, at its junction with Church Lane, where it joins the relatively recently named Hever Road with Mailings Cross.

Local opinion, erroneously believes that its name derives from there only being one well in the district, but it originates from its substrate, being once called ‘Shinglewell’ describing the substrate. It ended its days as a traditional winch well, with a depth of 150 yards. Watt (1917) described the draw well as having a sign, reading ‘This water is not fit for drinking’— the result of contamination by a nearby stagnant pond. This wooden framework was removed during the First World War, when the well was filled in and domed over. Later, in 1935, a granite slab inscribed with: ‘Site of the Ancient Well, Singlewell Parish or Ifield’ was placed there. Unfortunately, this was removed by the County Council in 1952, and along with the combination of road improvements, the site was largely forgotten.

Folklore

Recorded in a Latin MS and translated by the Rector of Ifield between 1912-1935, the Rev K. M. Ffinch tells of a tradition in great detail, and the following is a brief resume. The legend involves a village girl called Salerna, who is said to have ‘thrown’ herself down the well after being accused of stealing some cheese. Yet, as she fell, she cried out for St. Thomas to save her from her impending doom, and upon finishing her plea, landed on some planks lying at the bottom of the well. They broke her fall, and thus saved her from her dreadful fate. She was then subsequently rescued and because of the ‘miracle’ the well was dedicated to the saint.

The incident is said to have occurred soon after St. Thomas’s martyrdom, and is said to have been one of his first miracles. The name ‘Salerna’ suggests a Roman origin, supported by its location along Watling Street, a Roman Road. Bayley (1978), using a low-land British dialect, which he believed survived until this century, states that ‘Salire Naias’ is ‘the water nymph, who springs forth and runs down’. Consequently, the story of St. Thomas miracle may have been introduced to remove the pagan tradition and refocus the beliefs of the people using a local saint.

References:

- Bayley, M.,(1978) Ancient, and Holy and Healing Wells of the Thames Valley, and their Associations.

- Ffinch, K.M., (1957) The History of Ifield and Singlewell

- Parish, R.B., (1997) “The Curious Water-lore of Kent II: Ghosts, Fertility and Living Traditions”, in Bygone Kent, Volume 18, pp.427–32.

- Watt, F., (1917) Canterbury Pilgrims and their Ways

(Extracted from the forthcoming book Holy Wells and Healing Springs of Kent)

Links:

© R.B. Parish, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.

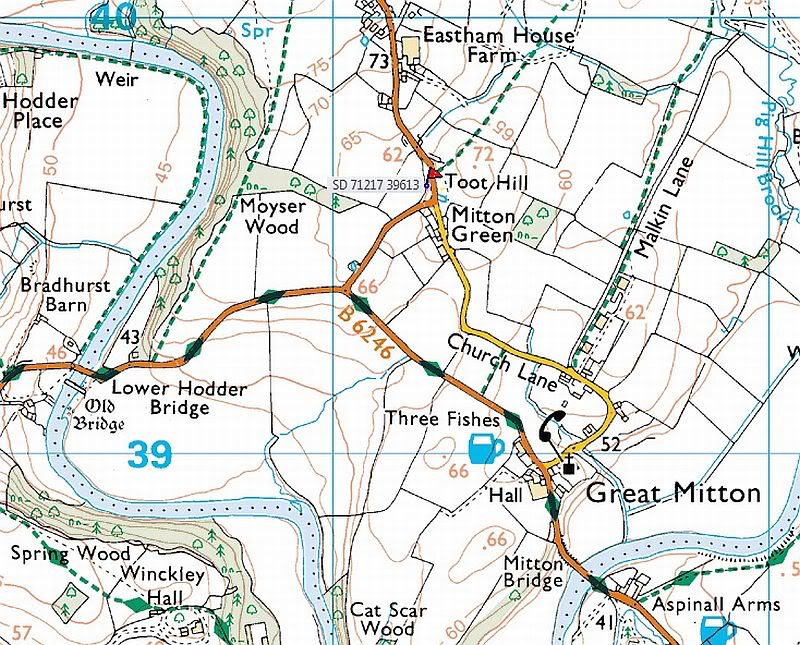

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.