Henge: OS Grid Reference – SE 01405 65413

In Grassington, go up the main street and keep going uphill, out of town. You’re on Moor Road now and it keeps going northeast for about a mile, where the small copse of trees grows just before Yarnbury House. However, on the other side of the road (right) two field before you reach the house, you’ll notice a slightly raised elevation in the field, close to the wall. A footpath runs right past it, so you shouldn’t have too much trouble finding it!

Archaeology & History

This is a fine, roughly circular neolithic monument, sat not-quite-on-the-heights, but still possessing damn good views all round (except immediately west), begging the question, ‘what on earth are you and why were you built here?’ Answers to which, we don’t really know. But ascertaining its geomantic nature wouldn’t be too difficult for local people who have spent years visiting the site. John Dixon (1990) mentioned how, in the winter months,

“the sun falls behind Pendle (Hill) providing it with a sky-red backdrop. In my own view the site is related to the presence of Pendle…and may have been the major factor in the location of the monument.”

He may be right! It has been suggested by one archaeologist (King et al, 1995) that the site was “most probably a wood henge” with upright rings of wooden posts that were built onto the central platform — but until we get a full dig here, we’re not gonna know.

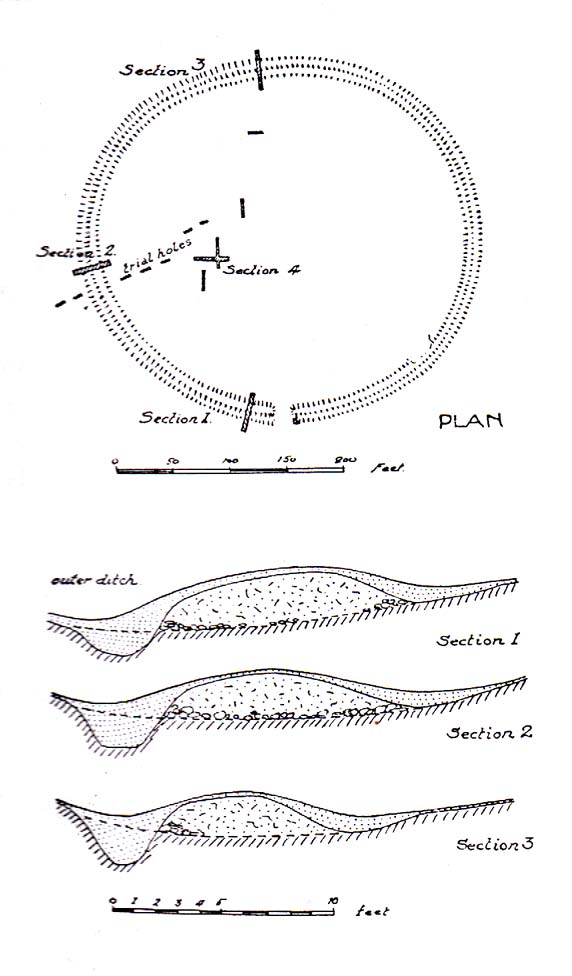

Found close to an extensive amount of other prehistoric remains in the area (dating from the neolithic to Iron Age), this henge monument is notable for its size, as it’s only a little fella! It’s like a mini-version of the Castle Dykes henge near Aysgarth, 14 miles to the north! First mentioned as a ‘disc barrow’ in 1929, J. Barrett (1963) added the Yarnbury Henge to the archaeological registers 32 years later, citing it as a “circular platform 60-63 ft diameter, surrounded by a ditch 20ft wide (crest to crest) and an outer bank.” A couple of years later D.P. Dymond (1965) described the henge in slightly more detail, telling:

“At Yarnbury, just over one mile north-east of Grassington there is an earthwork 116ft in diameter overall, consisting of a ditch with external bank. On surface inspection the earthwork appeared to have the characteristics of a henge monument. An excavation carried out in July 1964 , by an archaeological summer school based on Grantley Hall, proved this thesis. There was no trace of an internal mound and the entrance to the southeast was obviously original. No traces were found of any sort of internal structure, and a square pit in the centre of the circle had been caused by an excavation earlier this century. The ditch was rock-cut and the bank of simple dump construction. No dating evidence was found… With its single entrance the Yarnbury henge falls into Atkinson’s Class 1.”

In recent years it seems that some damage has been done by digging into the east and southeastern sections of the henge. Summat we hope doesn’t get any worse. In the field on the other side of the road we found traces of prehistoric enclosure walling (along with a curious, large, almost cursiform shadow, 44 yards across and running 110 yards NE), typical of the extensive settlement remains found less than a mile away at Lea Green and High Close Pasture, Grassington. It’s an impressive area, well worth checking out!

References:

- Barrett, J., “Grassington, W.R.,” in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, part 161, 1963.

- Beck, Howard, Yorkshire’s Roots, Sigma: Wilmslow 1996.

- Dixon, John & Phillip, Journeys through Brigantia – volume 2: Walks in Ribblesdale, Malhamdale and Central Wharfedale, Aussteiger Publishing: Barnoldswick 1990.

- Dymond, D.P., “Grassington, W.R.,” in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, part 163, 1965.

- Harding, A.F., Henge Monuments and Related Sites of Great Britain, BAR 175: Oxford 1987.

- Harding, Jan, The Henge Monuments of the British Isles, Tempus: Stroud 2003.

- King, Alan, et al, Early Grassington, Yorkshire Archaeological Society 1995.

- Wainwright, G.J., “A Review of Henge Monuments in the Light of Recent Research,” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 35, 1969.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.