Enclosure: OS Grid Reference – SE 0478 4987

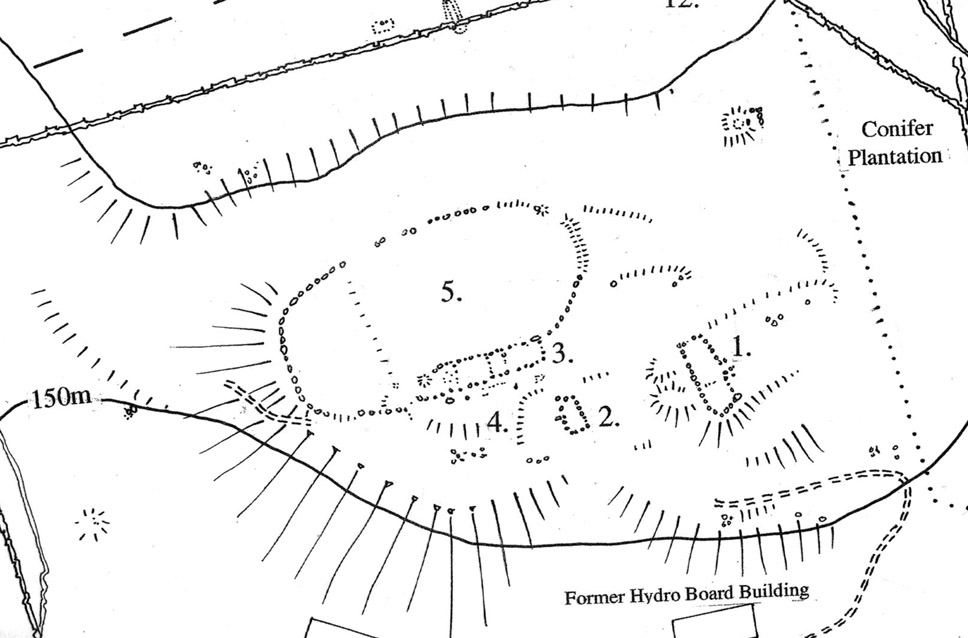

Take the A6034 road between Addingham and Silsden and, at the very top of the hill between the two towns, at Cringles, take the small road of Cringles Lane north towards Draughton. Less than a mile on, veer to left and go along Bank Lane until you reach the track and footpath on your right that takes you to Moorock Hall. On the other side of the Hall, take the track on your left, along the wallside; and where the track turns left again, look into the field on the other side of the wall. You can see some of the ditch and embankment running across the field.

Archaeology & History

Found within the southwestern segment of the gigantic Counter Hill enclosure, near Woofa Bank, Eric Cowling (1946) described “an almost obliterated fortification” which has certainly seen better days — though you can make out the ditched earthwork pretty easily at ground level. When T.D. Whitaker visited this place sometime before 1812, he described it as a camp that “was found to contain numbers of rude (?!?) fireplaces constructed of stone and filled with ashes.” He also thought the enclosure was Roman in nature.

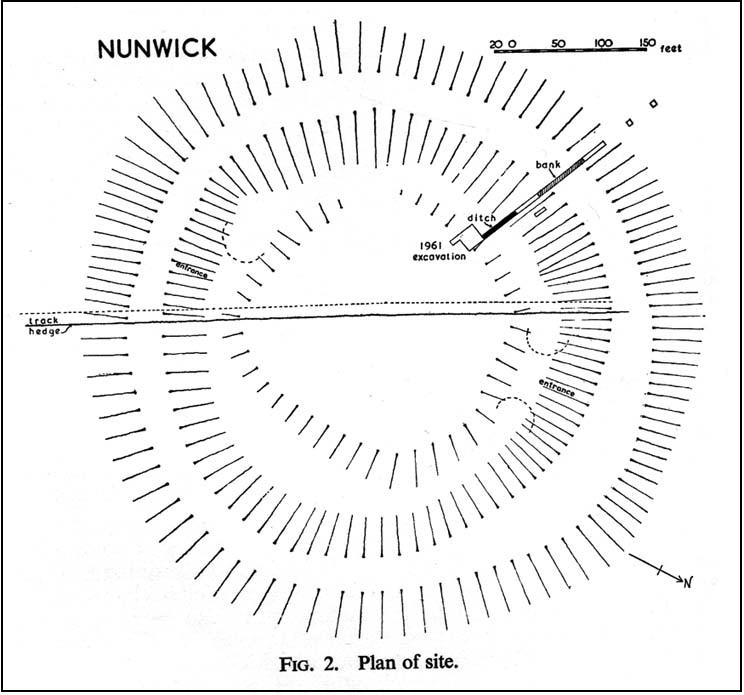

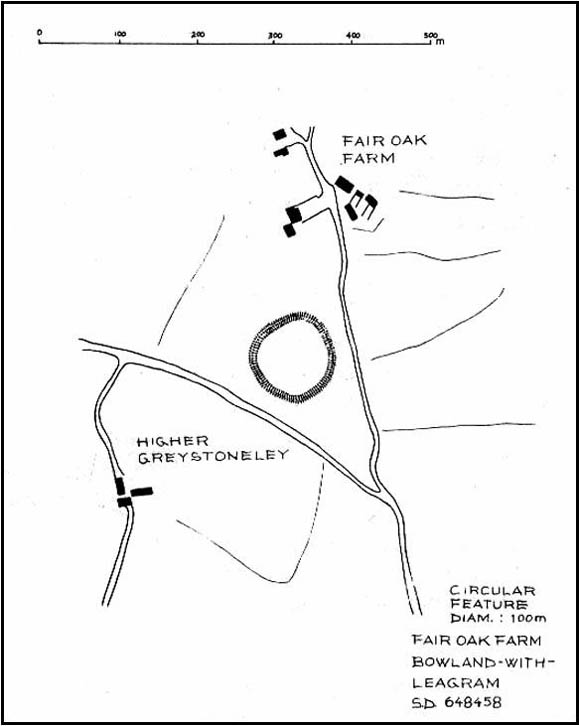

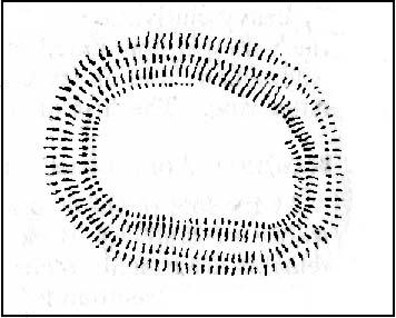

It’s a large site. Running around the outer edge of the embankment, this enclosure measures roughly 378 yards (345m) in circumference. It has diameters measuring, roughly east-west, 132 yards (121m); and north-south is 95 yards (87m). The ditch that defines the edges of the enclosure averages 6-7 yards across and is give or take a yard deep throughout — but this is not an accurate reflection of the real depth, as centuries of earth have collected and filled the ditch. An excavation is necessary to reveal the true depth of this. There also seems to have been additional features constructed inside the enclosure, but without an excavation we’ll never know what they are. Examples of cup-marked stones can be found nearby.

The Marchup Hill enclosure was described by the early antiquarian James Wardell (1869), who visited this and the other earthworks around Counter Hill. He told that this was,

“of oblong form, but broadest at the west end, and rather larger than the other. When the area of this camp was broken up, there were found some numbers of rude fireplaces constructed of stone and filled with ashes, and also a large perforated bead of jet.”

Modern opinion places the construction of this enclosure within the Iron Age to Romano-British period, between 1000 BC to 300 AD. E.T. Cowling (1946) thought the Iron Age to be most likely, but it may indeed be earlier. His description of the site was as follows:

“At the foot of the southern slope of Counter Hill and close to the head waters of Marchup Beck is an almost obliterated fortification. These remains are roughly rectangular, but one side is bent to meet the other; the enclosure has rounded corners and has a ditch with the upcast at each side. The inner area is naturally above the level of the surrounding ground. In spite of heavy ploughing, the ditch on the western side still has a span of fifteen feet and a depth of five feet between the tops of the banks. Whitaker states that the camp “was found to contain numbers of rude fireplaces constructed of stone and filled with ashes.” These hearths appear to be the remains of cooking-holes such as are often found on Iron Age sites… Cup and ring markings are close at hand, but no flints have been found or trace of Mid-Bronze Age habitation. The enclosure is badly planned, the upcast on the western side would aid an attack rather than the defence.”

…to be continued…

References:

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Wardell, James, Historical Notes of Ilkley, Rombald’s Moor, Baildon Common, and other Matters of the British and Roman Periods, Joseph Dodgson: Leeds 1869. (2nd edition 1881).

- Whitaker, Thomas Dunham, The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven in the County of York, (3rd edition) Joseph Dodgson: Leeds 1878.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.