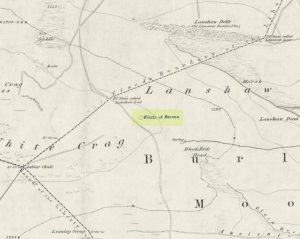

Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SD 9433 2543

Also Known as:

- Frying Pan Circle

- Roman Barrow

From Todmorden, take the road to Hebden Bridge (A646) less than half-mile outta town and just as road goes uphill, watch for the left turn up to Cross Stone. This is one helluva superb steep, winding road if you aint been up it before (which, somehow, I used to be able to cycle up without a break!). As you reach the hamlet of Cross Stone, bear uphill again (left) until you reach the top-end of the golf course, where you’ll see a footpath on your left that runs alongside the course. Walk on this until it reaches a stile. Walk up the wallside and onto the course itself – and there, in front of you, in the middle of the damn golf course, you’ll see the very denuded remains of a once fine prehistoric monument (it’s situation, quite frankly, is a disgrace – and any pagans or historians who feel similarly should complain to Calderdale Council about the lack of preservation here; as the more of us who do, the more they’ll have to pay attention and perhaps do something about it).

Archaeology & History

Very little can be seen of this once important site thanks to the important golf course built right on top of this once sacred site. Thankfully we have an extensive description of the place that was done by J. Lawson Russell (1906) from which this profile account — and every other account for that matter! — draws heavily upon. It was included in Aubrey Burl’s magnum opus (2000) as a stone circle, but this isn’t strictly correct and is more accurately a cairn circle or ring cairn monument.

It was thought in times past to have been a monument built by the Romans (hence the earlier title of ‘Roman Barrow’), but its origins were much earlier than those scruffy incomers! Its other local folk name, the “Frying Pan Circle” is, like its namesake at Morley, an etymological curiosity relating to the flat ground left in the wake of its shape: flat, circular, with raised edges surrounding it, not unlike a frying pan.

It was accurately described for the first time by Robert Law (1897), who later broadened his account of the site a year later in a paper he wrote for the Yorkshire Geological Society (1899) after an excavation here. Mr Law and others explored the centre of the ring where they believed it most probable to find remains of some form or another — and they weren’t to be disappointed! The following is taken directly from his lengthy article:

“On Thursday, July 7th of this year (1898), a very interesting and important archaeological discovery was made on a portion of land known as Higher Cross Stone Farm, belonging to Mr. Sutcliffe, of Todmorden. In a field on this farm, called Black Heath, a ring circle, made of earth, has long been known to exist, and has gone by the name of the “Frying Pan.” No history or tradition exists as to the origin of this circle, and various speculations have from time to time been indulged in by the residents. Some have called it a Roman Camp, others a fairy circle, others a circus ring, made to break in horses; but the excavations prove it to be a burial place of prehistoric times. Mr. Tattersall Wilkinson, of Burnley, a well-known archaeologist of considerable experience on ring circles, along with the writer of this article, came to the conclusion, on hearing of this circle, that it probably contained human remains, and an excavating party was organised to meet on the spot on the day above mentioned. This party met at the appointed time, and the plan of operations was to find the centre of the circle, by means of a tape, then to dig a circular trench about three feet from the centre, in which space it was thought the remains would lie. The ring was nearly a perfect circle. It was raised conspicuously above the ground. The rim of raised earth was about three feet wide, and the diameter of the whole circle was thirty yards. After the digging had been going on for a short time, burnt soil and charcoal were met with, and the top of an urn was exposed to view. The diggers then went to work with the greatest possible care, and very soon a beautiful urn was laid bare exactly in the centre of the ring. The urn was embedded in charcoal and calcined bones. It was ten inches high and nine inches at the top, tapering to about three inches wide at the bottom. There was a rim or collar in the upper part of the um about three inches deep, which stood out about one inch in relief from the lower part of it. The collar was ornamented, probably by a pointed stick, with the herring-bone pattern. The outer part of the um was plain. In clearing away the debris from the urn another one was discovered, different in pattern and less in size, but in a very perfect state of preservation.

“About two feet from this, on the opposite side of the central urn, another um was discovered and laid bare, by carefully digging round it with a trowel. This urn was also in a good state of preservation, and about the size of the second one, but differently ornamented. These smaller urns were the same shape as the larger central one, but the ornamentations were not so fine, and they were made of inferior clay. On the south side of the circle, about two feet from the centre, another urn was discovered, but it appeared to be insufficiently baked when manufactured, and had decomposed and crumbled into dust. From the inside of this urn a large quantity of calcined human bones and charcoal was dug up, but the bones were very fragmentary, and the sex of the person to whom the bones belonged could not be determined. Several portions of cranium, rib bones, and lower and upper leg bones were found among the debris.

“Within a few inches of this urn two small (so called) incense cups were found. One of them was very perfect and in an excellent state of preservation and was beautifully ornamented all over. These cups were about three inches in height and three and a half inches in diameter, but tapered a little at the bottom. Indications of three other urns were observed, but they were so much decomposed that little or nothing could be made of them. The others seemed to be arranged about the large central urn and about two feet apart. When the earth had been cleared away from the three perfect urns, and before they had been removed, several photographs were taken of them in situ. One of the smaller urns leaned a little to the south. Several pieces of flint and chert were dug out of the excavation. The urns and incense cups being removed were put into baskets and conveyed to Todmorden, where they were re-photographed and placed in the Free Library for their safe keeping.

“On July 13th, six days after the “find,” the urns were opened at the Co-operative Hall, Todmorden, before a very large gathering of scientific ladies and gentlemen drawn from the surrounding districts. Mr Tattersall Wilkinson, Dr. Crump of Burnley, and the author were entrusted with the opening of the urns.

“The largest one, which was of superior make to the other, was the first to be operated upon. The work was tedious and was done in the most careful way possible. Each operator commenced to pick out by means of a small pocket knife the substances deposited in the urns, and the material was closely examined as it fell out on the table. For the first half-hour or so nothing particular was found. The contents which had been so far dug out were portions of broken urns of a similar pattern to the urn that was being examined, but were not portions of it and must have been placed there as filling-in material. Along with these urn fragments there was some dark brown sand, which appeared to have been burnt, quantities of bituminous soil, small fragments of bones, and bits of charcoal. As the examining party dug deeper into the urn human bones became more numerous and in larger fragments and of a more determinable character, and this went on until the urn had been half emptied. The rest of the contents of the urn then showed signs of being almost entirely calcined bones, and bone after bone was picked out, examined, and laid on the table. Among these bones were fragments of various sizes: of cranium, portions of scapula, pelvic bones, femur, tibia and other bones of the legs. Besides these there were fragments of ribs and perfect toe bones.

“Presently a small cup was laid bare inside the urn, and a few pokes with the knife so far emptied it of its contents that an ancient relic could be seen which differed from any that had yet been found. A moment later a piece of metal was picked out of the cup resembling a spear head. It was about 2½ inches long and 1¼ inches wide at one end, and tapered to a point at the other. It was thin and flat and sharp at the sides and point. It contained a rivet at the two extremities and another one about half way up one side. A bronze pin was also found about the same time as this piece of metal, and on careful examination the metal and the pin were made out to be a bronze brooch, the pin having probably been detached in extracting it from the bones in the cup. Besides this brooch about a dozen beads of a necklace were found, which were chiefly of a rounded shape and about half an inch in diameter. Some of the beads seem to have been made of jet, and some of bone, and were more or less rudely carved. A bone pin was next brought to light. It was almost two inches in length and the eighth of an inch in diameter at one end, tapering towards a point at the other. It was cylindrical in form and slightly curved. The fact of all these ornaments having been carefully placed in the cup and buried with the urn point to the cup having been used as a utensil in which to preserve what was considered of great value. Several human teeth were also found in this cup.

“The opening of the two inferior urns proved that they contained nothing more than the sweepings up of the funeral pile which probably took place after the calcined bones had been placed in the more important urn.

“Since this discovery was made a beautifully-formed flint arrowhead of the leaf-shaped pattern has been found in the same hole from which the urns were dug. There have also been two or three more urns discovered within the same circle, but their contents have not yet been disclosed.”

They had to wait a few more years before a more complete account described the contents of the “two or three more urns” at Blackheath’s circle. That duty fell to Mr J. Lawson Russell (1906), who, after further excavations, wrote the most detailed and complete account of the place.

Following the successful discoveries in 1898, Messrs. Russell, Law, Wilkinson and others made a “further systematic examination of the whole circle”, which was then subsequently wrote up in Ling Roth’s Prehistoric Halifax. The following is a detailed account of that second dig:

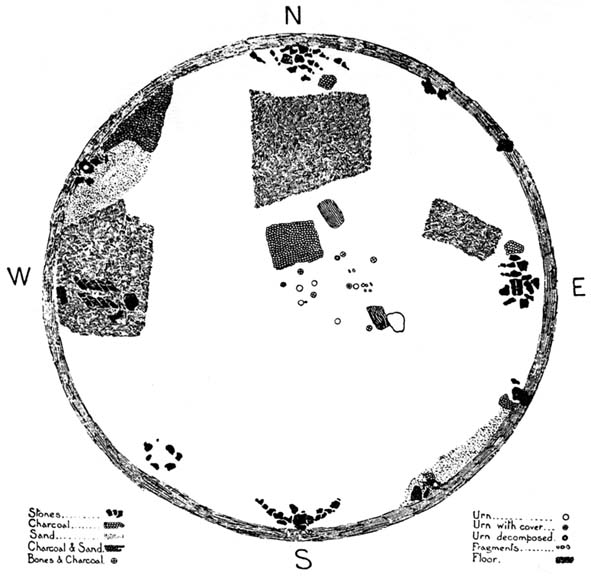

“The first step in the systematic examination was the breaking up of the circle into quadrants. This we did by running deep trenches north, east, south and west. The turf was then removed and these quadrants dealt with seriatim. The diameter of the circle was as nearly as possible 100ft (30.5m), i.e. measuring from ridge to ridge, but the slight mound which marked the circumference sloped gently further into the general level of the field. Eight or nine deep furrows ran through the circle, from north to south, cutting the vallum up into segments and ploughing the enclosed area with their parallels. The method we followed was to trench till we came to soil which had never been disturbed. Generally about two spade grafts brought us to stiff glacial (?) clay. When we came upon an urn its position was carefully observed with reference to the centre and noted on a plan ; the earth was removed by trenching round the um, which was photographed in situ when sufficiently defined. The urns were not deeply placed, some of them being only six inches from the surface, none deeper than from 18in to 2ft (46 cm to 61 cm), and all of them without exception were set in the ground upright on their bases, not inverted. There was in the centre an urn, and this was surrounded at a radius of 2ft by a ring of deposits; two having urns, the others either having no urn at all or showing signs only of disintegrated pottery. At a distance of about 10 ft. from the centre another series of deposits was radially arranged, but all to the east side of the north to south centre line. It will be seen that, if we leave out of account the urn found in the vallum in the north-west quadrant, all the urns and deposits save one have been placed to the east of the north to south centre line.

“An extensive floor of charcoal, sometimes an inch to two inches in thickness, was defined to the north of the centre, and two deep pits were located about 16ft (4-9 m) from the centre, one in the north-east and one in the south-east quadrant. Close to that deep spot in the south-east quadrant we found a curiously baked surface which we attempted to photograph. A group of urns, one of which was a fine covered specimen, lay in line going due east from the centre ; and this group had placed all round it flat stones of no great size, set on edge, as if to protect the urns or mark them off from others.

“In the northern half of the circle and lying largely in the NE quadrant, was a considerable area showing a closely beaten, hard baked red floor, with pieces of charcoal speckled amongst the general red. Somewhat similar areas occurred at the west and at the east sides of the circle, that at the west being most marked, the whole floor in that quarter looking like disintegrated pottery closely trodden together.

“Lying NW by W, from the centre, we found in the vallum a large stone with an urn set right in its middle. Other stones lay near, as if they might have been set round this urn in kist fashion. All about this spot the ground seemed to be made up of shivers of sand stone and pounded sand. Over-lying this sand for a considerable area going northwards was a thick layer of charcoal. Curious cairns of stone had been placed just inside the vallum, and these, we soon discovered, accurately marked the cardinal points — N, E, S and W., the most curious of these cairns being that which lay exactly south. The stones here were in the form of a semi-circle, having an armchair -like arrangement in its middle, the back of the chair looking due south, i.e., by the sun at mid-day. In the turf over-lying this strange assemblage of stones a portion of the base of an urn was found, and there was abundance of charcoal at the westerly horn of the semi-circle. Many of the stones in the other cairns lay in groups of three pointing in one direction. Some of the groups looked as if they had been upright at one time and thrown down. At the western point the stones lay in an imbricated fashion, inclined at an angle of about 45°, placed in two rows, about 2½ft (76 cm) apart, five in one row, four in the other. A large flat stone lay near, and by it one which probably was the fifth of the second row. Between these rows of stones, and all around them, lay great quantities of what looked like partly baked clay or disintegrated pottery. In the southwest quadrant lay an incomplete ring of stones, which possibly marked an interment. This incompleteness is interesting and may have had some significance t Other large stones were found set into the vallum at more or less regular intervals. Some of these are still in situ, the further examination of the vallum having had to be abandoned. Close by all these stones charcoal was found, and the upper surface of one, at least, that in the SE quadrant, SE of centre, was blackened as if by fire.

“In removing the stones forming the four cairns I examined all of them for signs of markings, but none was seen except one deeply scored line drawn across the large flat stone in the cairn at the eastern point. This line may have been grooved into the stone by the over-passing plough, but I am rather of opinion that it was purposely graved there. What was the purpose of these cairns and large stones in the vallum? The fact of one large um having been found as already stated, on a stone in the vallum, while part of another urn was found near the southern cairn, suggests a probable explanation for some of these arrangements of stones. They may have been rude kists enclosing urns, or at least they may be regarded as stone-marked interments. The presence of charcoal close beside these stones may point to the performance of funeral rites.”

Mr Russell then went into considerable details describing the urns, flints, carved bones and other objects recovered from the site (those who would like further info, find a copy of H.L. Roth’s Yorkshire Coiners for the full account). It was his opinion that the site was used primarily as a place for the dead. There was no evidence here of domestic activity or settlement of any kind. And particularly intriguing were the four cairns placed inside the circle: each one at the cardinal points north, south, east and west. This would indicate a ritual evocation of the airts, or spirits of the four directions, with obvious correlates in relation to spirits in the land of the dead. This was very obviously an important sacred site to the people who built this… Oh such a pity it’s now in the state it is…

One other point of intrigue here is: according to the archaeological records there are no other prehistoric sites nearby, nor any settlement remains that could account for the existence of this once important ritual site. That doesn’t make sense…

Folklore

Old lore told that this site was once the abode of the fairy folk. The old game of Knurr and Spell used to be played here; which is a game played with a wooden ball (the knurr) which is released by a spring from a small brass cup at the end of a tongue of steel (the spell). When the player touches the spring, the ball flies in the air and is struck with a bat. In J.L.Russell’s (1906) account of the excavations here, he reported finding several very old balls in the circle, indicating that Knurr and Spell or variants of this game had been played here for many centuries.

Even weirder was the UFO encounter here. In 1982, the landowner’s wife reported seeing an earthlight right next to the spot, as she looked from her bedroom window. The next thing she knew, she was laid outside prostrate on the ground right next to this ancient monument.

…to be continued…

References:

- Abraham, John Harris, Hidden Prehistory around the North West, Kindle 2012.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Fishwick, Henry, “Discovery of Ancient British Barrow in Todmorden,” in The Reliquary, New Series volume 9, 1903.

- Holden, Joshua, A Short History of Todmorden, Manchester University Press 1912.

- Law, Robert, “Evidences of Prehistoric Man on the Moorlands in and around the Parish of Halifax, in Halifax Naturalist, volume 2, April 1897.

- Law, Robert, “The Discovery of Cinerary Urns at Todmorden,” in Halifax Naturalist, volume 3, August 1898.

- Law, Robert, “On Recent Prehistoric Finds in the Neighbourhood of Todmorden,” in Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological & Polytechnic Society, volume 13, 1899.

- Roth, H. Ling, The Yorkshire Coiners, 1767-1783; and Notes on Old and Prehistoric Halifax, F.King: Halifax 1906.

- Russell, J. Lawson, “The Blackheath Barrow,” in Ling Roth’s Yorkshire Coiners (Halifax 1906).

- Watson, Geoffrey G., Early Man in the Halifax District, Halifax Scientific Society: Halifax 1952.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.