‘Stone Circle’: OS Grid Reference – NG 2725 5273

Also Known as:

- Annait

- Temple of Annait

Getting Here

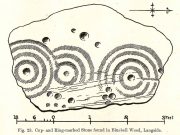

1880 map of Anaitis

Otta Swire (1961) told how to find this place, thus: “The Waternish road turns off to the north at Fairy Bridge, whence it runs along the valley of the Bay river. On the left of the road, though at some little distance from it, where the river cleaves its way through a gorge to the sea, stands the mound which is now all that remains of the ‘Temple of Anaitis’ (so called).”

Archaeology & History

This is a curious place, full of archaeological potential if the folklore and history records are owt to go by, yet little of any substance remains to substantiate what may have been an important stone circle or other heathen site in earlier times. It seems to have been described first of all in the famous Hebridean journeys of Boswell and Johnson in the late 18th century. Amidst his insulting description of both the landscape and local people, on Friday 17th September 1773, James Boswell visited the site and told:

“The weather this day was rather better than any that we had since we came to Dunvegan. Mr M’Queen had often mentioned a curious piece of antiquity near this which he called a temple of the goddess Anaitis. Having often talked of going to see it, he and I set out after breakfast, attended by his servant, a fellow quite like a savage. I must observe here, that in Skye there seems to be much idleness; for men and boys follow you, as colts follow passengers upon a road. The usual figure of a Sky boy, is a lown with bare legs and feet, a dirty kilt, ragged coat and waistcoat, a bare head, and a stick in his hand, which, I suppose, is partly to help the lazy rogue to walk, partly to serve as a kind of a defensive weapon. We walked what is called two miles, but is probably four, from the castle, till we came to the sacred place. The country around is a black dreary moor on all sides, except to the sea-coast, towards which there is a view through a valley, and the farm of Bay shews some good land. The place itself is green ground, being well drained, by means of a deep glen on each side, in both of which there runs a rivulet with a good quantity of water, forming several cascades, which make a considerable appearance and sound. The first thing we came to was an earthen mound, or dyke, extending from the one precipice to the other. A little farther on, was a strong stone-wall, not high, but very thick, extending in the same manner. On the outside of it were the ruins of two houses, one on each side of the entry or gate to it. The wall is built all along of uncemented stones, but of so large a size as to make a very firm and durable rampart. It has been built all about the consecrated ground, except where the precipice is deep enough to form an enclosure of itself. The sacred spot contains more than two acres. There are within it the ruins of many houses, none of them large, a cairn, and many graves marked by clusters of stones. Mr M’Queen insisted that the ruin of a small building, standing east and west, was actually the temple of the goddess Anaitis, where her statue was kept, and from whence processions were made to wash it in one of the brooks. There is, it must be owned, a hollow road visible for a good way from the entrance; but Mr M’Queen, with the keen eye of an antiquary, traced it much farther than I could perceive it. There is not above a foot and a half in height of the walls now remaining; and the whole extent of the building was never, I imagine, greater than an ordinary Highland house. Mr M’Queen has collected a great deal of learning on the subject of the temple of Anaitis; and I had endeavoured, in my journal, to state such particulars as might give some idea of it, and of the surrounding scenery” —

But in all honesty it seems Mr Johnson was either too lazy to write about the place, or simply didn’t actually get there, in spite of what he alleged! But later that evening, Boswell dined with the same Mr MacQueen, who told him more of this site. In the typically pedantic tone of english supremacy (which still prevails in some idiots who visit these lands), he continued by saying:

“Mr Macqueen had laid stress on the name given to the place by the country people, Ainnit; and added, ” I knew not what to make of this piece of antiquity, till I met with the Anaitidis delubrum in Lydia, mentioned by Pausanias and the elder Pliny.” Dr. Johnson, with his usual acuteness, examined Mr Macqueen as to the meaning of the word Ainnit, in Erse, and it proved to be a water-place, or a place near water, “which,” said Mr. Macqueen, “agrees with all the descriptions of the temples of that goddess, which were situated near rivers, that there might be water to wash the statue.”

There ensued a discussion between Mr MacQueen and Samuel Johnson about the etymology of ‘Anaitis’, with one thinking it was of a goddess, and another that it represented an early christian site. To this day it is difficult to say what the word means with any certainty. In W.J. Watson’s (1993) fine work he tells us,

“Andoit, now annaid, has been already explained as a patron saint’s church, or a church that contains the relics of the founder. This is the meaning in Ireland and it is all we have to go upon. How far it is held with regard to Scotland is hard to say… They are often in places that are now, and must always have been, rather remote and out of the way. It is very rarely indeed that an Annat can be associated with any particular saint, nor have I met any traditions connected with them. But wherever there is an Annat there are traces of an ancient chapel or cemetery, or both; very often, too, the Annat adjoins a fine well or stream…”

The great Skye historian and folklorist Otta Swire (1961) also wrote about this mysterious site, mainly echoing what’s said above, but also adding:

“This name of Annait or Annat is found all over Scotland. It has been interpreted as meaning the ‘Water-place’ from Celtic ‘An’ = water, because many are near water. Others suggest ‘Ann’ = a circle (Celtic) and claim that most Annats are near standing stones. The most-favoured derivation seems to be from Ann, the Irish mother of the Gods, and those who hold this view claim that the Annats are always near a revered spot, where either a mother-church or the cell of a patron saint once stood. Probably Annat does, in fact, come from an older, pre-Celtic tongue, and belongs to an older people whose ancient worship it may well commemorate. The curious shape of the Waternish Temple of Anaitis and its survival make it seem likely that it was something of importance in its day, built with more than usual care and skill. Perhaps the Temple tradition is correct – but whose, if so, and to what gods? One cannot help wondering if cats played any part in its ritual, and if so, if any faint memory remains, for the nickname of the people of this wing was ‘Na Caits’ = The Cats, and not far off, by one of the tributary burns on the right of the roadway, there stands a small cairn, crowned by a long, sharp stone somewhat resembling a huge claw. This is the ‘Cats’ Cairn’.”

The Cats’ Cairn (NG271526) is said to mark the grave of a young boy from the 18th century, who was buried where he died and its story is told elsewhere on TNA. Another example of the Annait place-name can be found elsewhere on Skye at the megalithic site, Clach na h’annait.

References:

- Boswell, James, The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson, National Illustrated Library: London 1899.

- Swire, Otta F., Skye: The Island and its Legends, Blackie: Glasgow 1961.

- Watson, W.J., The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, Birlinn: Edinburgh 1993.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian