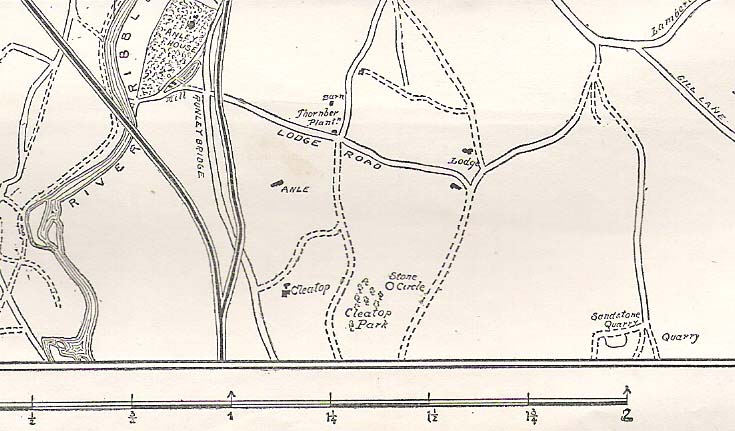

Legendary Rocks: OS Grid Reference – SD 97969 36483

Also known as:

- Penistone Crags

- Wuthering Heights

Go west through Stanbury village towards Lancashire for a mile till you reach the end of Ponden Reservoir. Where the water ends, follow the small track up to, and past, Whitestone Farm, till you reach the stream. Follow the valley up…

Archaeology & History

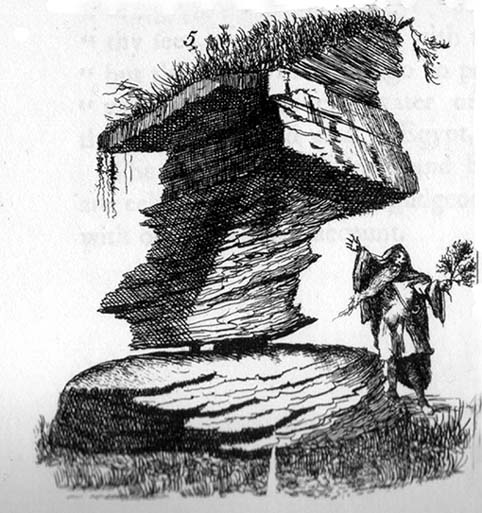

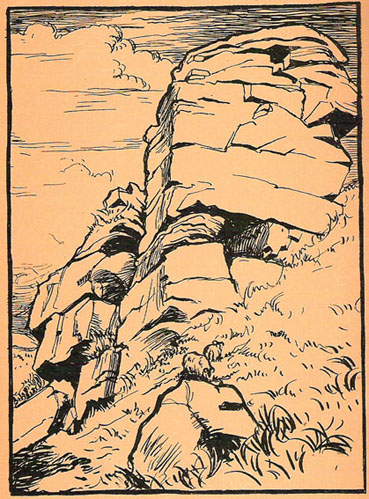

As the great Yorkshire historian J. Horsfall Turner (1879) told, “Ponden Kirk consists of a ledge of high rocks, dry in summer, but forming a stupendous cataract after heavy rain. It was here that Mrs Nicholls (Currer Bell) caught a severe cold shortly before her death.” The site is a fine one – not to be attempted from the base by unfit doods, unless you’re really serious about your climbing! But to those of us who like clambering up rocks and wholesome scenery, walk to the site via the stream (Ponden Clough Beck) and get to the cleft in the rock face. Tis a truly fine place!

In 1913, one writer posited the notion that the opening in the rocks through which local folk crawl (see Folklore, below) “is seemingly artificial” – which aint quite true, sadly.

Once on the tops above the Kirk, you’ve one helluva decent view, be it raining or sunny. On the far northeastern horizon arises the great omphalos of Almscliffe Crags; and next to that is the elongated top of Baildon Hill; and a little further northeast is Otley Chevin. It would be good to visit here on a few of the old heathen days and watch the sunrise, just to see if there are any intriguing solar observations to be made! (take a tent though – or p’raps, if you’re like us, don’t bother, but you’ll be bloody cold for the night!) The only potential sunrises of heathen significance appear to be midsummer and Beltane….

For me at least, one of the things which gives this site an intriguing form of sanctity is the fact that the Kirk itself forms the head at the end of the valley. It is a very fine ritual site and would obviously have had much more to be said of it than just the heathen marriage rites which are left today. The forces of wind and rain scream from its height, and in the valley beneath the chime of the gentlest echoes resonate, giving an altogether different ‘spirit’ amidst the same land. Those old cherubs of ‘male’ and ‘female’ spirit commune potently here – no doubt being the ingredients which gave form to the marriage customs… Those of you into feng-shui (the real stuff, not the modern bollox) and genius loci should spend time with the water and rocks here and you’ll see what I mean. Archaeologists amongst you, if you dare, should amble aimlessly here for sometime…for many hours, a few times, and give yourselves a notion of the ‘ritual landscapes’ you like to write about from the safety of your textbooks, to get a bittova better notion of what ‘experiencing the land’ is actually about.

This rocky outcrop was also said to be the place that Emily Bronte used in her Wuthering Heights novel as the place called Penistone Crags. A couple of other local writers have also added this legendary place in their tales aswell.

Folklore

Alleged by Elizabeth Southwart (1923) “to be of druidical origin,” the first literary note of this great rock outcrop appears to come from the reverend James Whalley (1869) of Todmorden, who in his romantic amblings over the moorlands here, told that if any gentleman wants to get married,

“he must by all means pay a visit to Ponden Kirk… Here ‘they marry single ones!’ Any lady or gentleman who can successfully ‘go through one part of the rock’ (which is quite possible) is declared to all intents and purposes duly married according to the forms and ceremonies of Ponden Kirk.”

His wording here seems to imply that the event of passing through the rocky opening, is in itself a confirmation of the ceremony of marriage, not needing the blessing of some strange christian rites. If so, this tradition would be a very ancient one indeed, making the stone the witness to the marriage event. This would be a rite witnessed by the stones themselves: a universal heathen attribute found in most of the ancient traditional cultures. But this curious unwritten history was to be echoed a decade later by that great Yorkshire historian, J. Horsfall Turner (1879), who told us that,

“at Ponden Kirk, as at Ripon Minster, a curious wedding ceremony is frequently observed. It consists in dragging one’s-self through a crevice in the rock, the successful performance of which betokens a speedy nuptial… The place is now frequently called ‘Wuthering Heights. Apart from the association of such names as Crimlesworth and Oakden (see the Alcomden Stones), fancy easily ascribes a druidical settlement at the Kirk.”

A not unreasonable assumption – though nothing of this nature, of yet, has been found.

That other great Yorkshire writer, Harry Speight — aka Johnnie Gray (1891) — echoed the same folklore telling how,

“The natives of these parts have a saying, ‘Let’s go to Ponden Kirk where they wed odd ‘uns,’ which has its origin in an old custom of passing through an enormous boulder… The belief is that if you pass through it, you will never die single. No one knows how the rock acquired its name, but the Saxon kirk suggests a temple of worship, possibly extending back to the druidical times.”

A few years later, Mr Whiteley Turner came here and he too affirmed the old wedding rites, also telling that “according to tradition, maidens (some say bachelors too) who successfully creep through the aperture will be married within the year.” This bit of info also shows that the rocks also had oracular properties – a function known at countless other sites.

The proximity of Robin’s Hood Well, just a couple of hundred yards away, beckons for association with the Ponden Kirk – which it obviously had… But that’s a tale to be told elsewhere…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Craven, Joseph, A Bronte Moorland Village and its People: A History of Stanbury, Rydal: Keighley 1907.

- Crawley, Ernest, The Mystic Rose: A Study of Primitive Marriage, Watts & Co: London 1932.

- Gray, Johnnie, Through Airedale from Goole to Malham, Walker & Laycock Leeds 1891.

- Southwart, Elizabeth, Bronte Moors and Villages, Bodley Head: London 1923.

- Turner, J. Horsfall, Haworth, Past and Present, J.S. Jowett: Brighouse 1879.

- Turner, Whiteley, A Spring-time Saunter Round and about Bronte Land, Halifax Courier 1913.

- Whalley, James, The Wild Moor, Edward Baines: Leeds 1869.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Judith Spolander for her correction on my Bronte glitch.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian