Legendary Rocks: OS Grid Reference – SE 210 649

Also Known as:

- Brimham Crags

From the lovely village of Summerbridge (near Pateley Bridge), go up the steep Hartwith Bank road, going straight across at the crossroads for another few hundred yards, passing the old tombs of Graffa Plain on your right…and they’ll start appearing on your left-hand side (west). Do not go into the expensive National Trust car-park. Instead (if you’ve already gone too far), about 100 yards before the Car Park you’ll find a small dirt-track on your left a short distance away. But if you drive past the rip-off car park, another 100 yards on there’s another spot where you can easily park up on the right-hand side of the road. Then cross the road and follow y’ nose…

Archaeology & History

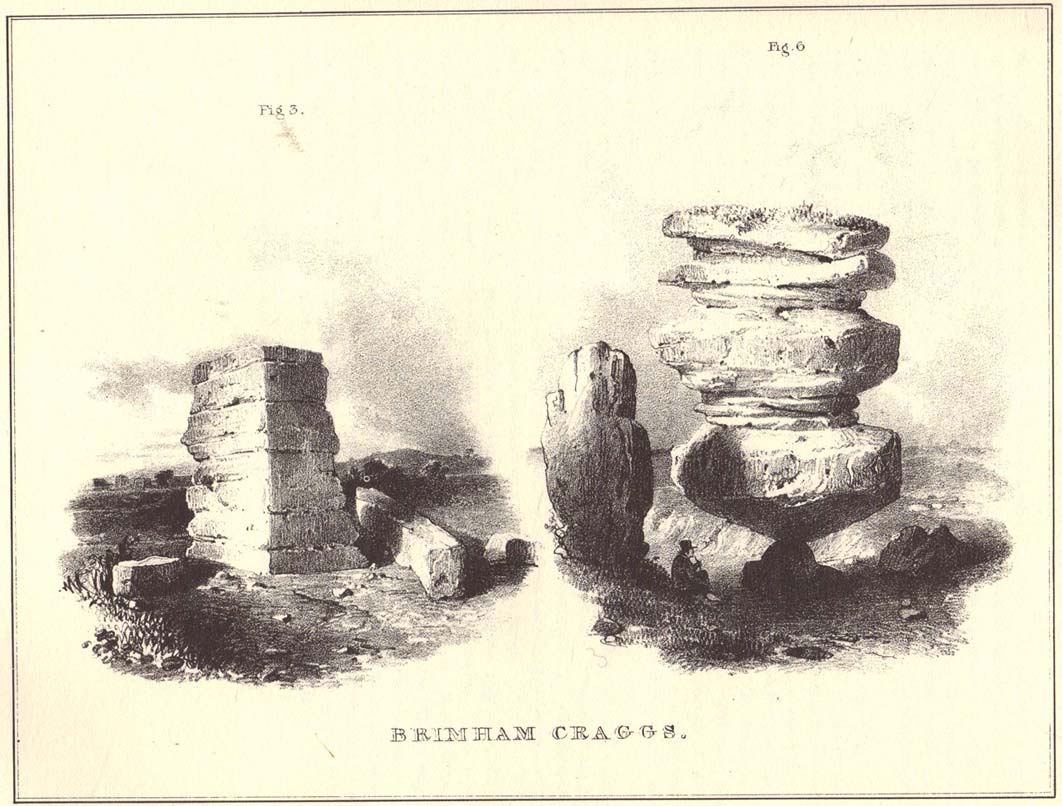

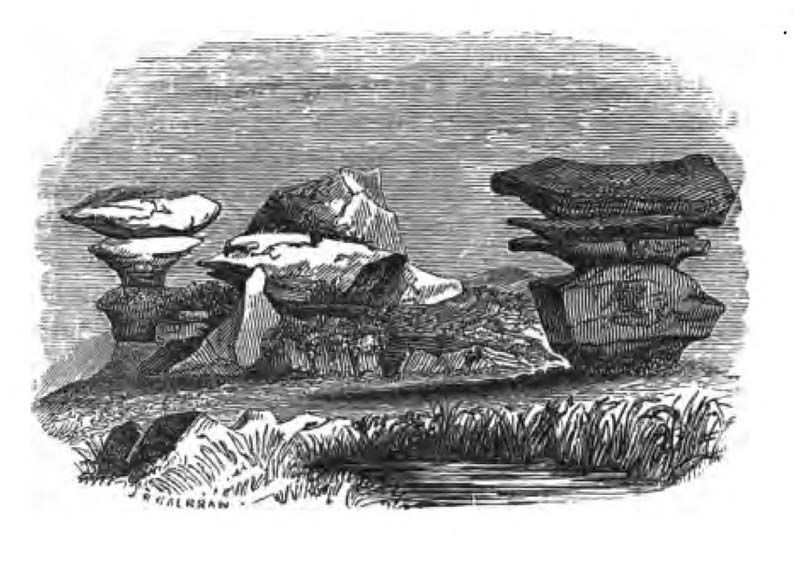

The OS grid reference given above is an approximation — for obvious reasons. This is a huge area that’s covered by Britain’s finest natural megalithic features, obviously sculptured by Nature Herself — though many are the historians who sought to give Druids the credit here. God knows how! The area over which these magnificent rock sentinels live covers some 60 acres and is some 1000 feet above sea level. The view from the hill around which the encircling parade of rocks guards is excellent, allowing our eyes to catch focus on the distant lands of Whernside, Simon’s Seat, York Minster, the Cleveland Hills and Kilburn’s white horse. It’s quite a view.

But this tends to be overlooked when you first visit the place, as the rocks which surround and walk alongside you overwhelm with impressions not encountered before. To those with spirit, you’ll be bouncing and running all day here, clambering upon rocking stones, jumping between dodgy gorges that await falls, and just aching to climb pinnacles that deny you. But then, if you need the selfishness of silence, this arena will only grant such solace when the rains are about, or dense fog and low cloud keeps others from this haunting amphitheatre. And it’s not surprising… The mass of rocks contort into the most beautiful and curious simulacra, which would not have gone unnoticed, nor deemed unimportant in the sacred landscape of our ancestors…

Brimham Rocks have been written about since the 17th century, though they didn’t receive the serious attention of outsiders until the 19th, when numerous Victorian writers — from antiquarians and geologists, to archaeologists and Druids — got to hear about the place. And by the beginning of the 20th century, a veritable mass of articles had been written in journals and travelogues of all persuasions! These quiet Yorkshire Rocks had become truly famous!

A lengthy essay was written in the distinguished archaeology journal of its time, Archaeologia, by northern historian Hayman Rooke (1787), who thought that some of the rocks here had been tampered with by the druids; with the legendary Cannon Rock in particular possessing oracular properties. The site as a whole was, he posited, a temple for Druids in ancient days. Certainly the place would have been deemed as sacred, whether by the druids or our more remote neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors.

In Harry Speight’s magnum opus, Nidderdale (1894), he described these rocky giants as best as he could, admitting as others before and since, that no mere words can convey the impression that only a personal encounter liberates, saying:

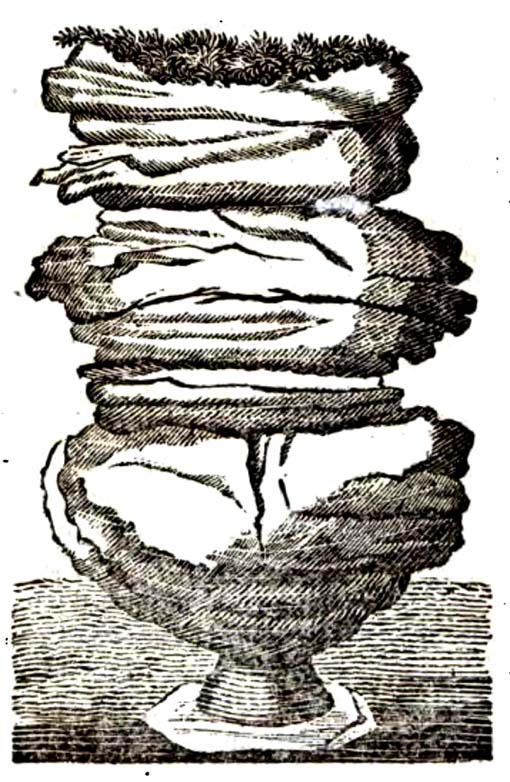

“The Brimham Rocks are among the greatest natural wonders of Yorkshire, and many have been the theories from time to time advanced as to the cause of their extraordinary aspects… The resemblances to natural and artificial objects are most striking. There we have the Elephant Rock, the Porpoise Head, the Dancing Bear (a very singular, naturally-shaped specimen), the Boat Rock, showing the bow and stern completely, etc. Then there is the great Idol Rock, a most mysterious-looking object, of almost incredible size and form. It is a perfectly detached block, fully twenty feet high, weathered along face joints into three roughly circular pieces, each from 40 to 50 feet in circumference, piled one above the other; the whole mass, weighing by estimation over 200 tons, being poised on a pyramid 3½ feet in diameter; the pivot itself supporting this immense column having a diameter of barely 12 inches.

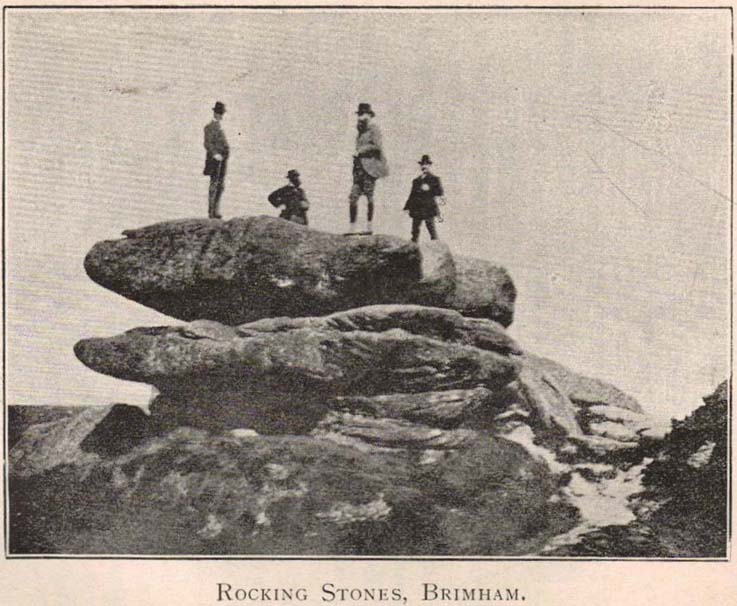

“East of the guide’s house are the famous Rocking Stones, consisting of a group of four rocks, which were discovered to be movable in the year 1786. The two on the west side weighing approximately 50 and 25 tons, require but little force to vibrate, while those on the east side, though much smaller are not so well poised and do not move readily. Each of the larger stones has a basin-like cavity on the top, and a kind of knee-hole open to the north, said to be the work of Druids. Close to the Rocking Stones are the appropriately-named Oyster-shell Rock, and the Hippopotamus’ Head. Turning now some thirty yards north of the Idol Rock we ascend Mount Delectable, where is the agreeable Courting or Kissing Chair, happily at not too close quarters with the above Hippopotamus’ Head and Boar’s Snout. The Chair consists of a single seat, but why it should be so called, I had better leave the amorous lover to solve. West of these is the more sober Druid’s Reading Desk, with its church-like lectern on a stout stone base. The we come to the Lover’s Leap, a gigantic and abrupt face of beetling crag, weathered to the west, and rising to a height of 60 to 70 feet, with three immense fragments balanced in a very remarkable manner at the summit. The rock is in tow principal sections, and an iron hand-rail has been fixed across the chasm to enable visitors to look down from the top. Further south are the Frog and Tortoise Rocks, the latter presenting from one point of view a capital resemblance to a tortoise creeping up the face of the crag towards the imaged frog. A little below this is a good imitation of a cannon, projecting from the edge of the cliff. In addition to these singular resemblances there are many others which the guide points out, such as the Yoke of Oxen, Mushroom Rocks, Druid’s Oven, Dog’s Head, Telescope, and the curiously perforated Cannon Rock, etc.”

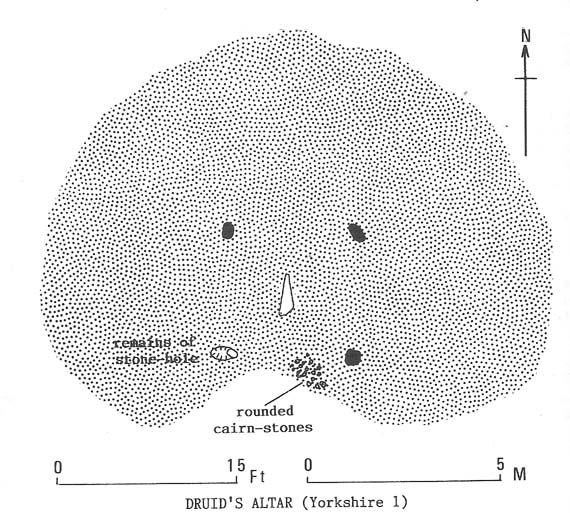

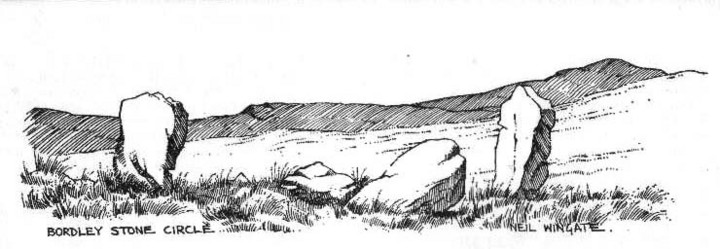

In a later work, Speight (1906) also mentioned the existence of a Druid’s Circle some 300 yards west of the main natural temples, but this site appears to have been destroyed. Thankfully the large standing stone on Hartwith Moor, a mile to the south, can still be found upright…

Folklore

In folklore, there’s little surprise this place was held by just about every 18th and 19th century historian as a ‘druidic site.’ But more interesting – in the light of Paul Devereux’s (2001) work on acoustic archaeology – is what Edmund Bogg (c.1895) said of these huge contorted stones:

“In bygone days these immense stones were supposed to be the habitation of spirits. The echo given from the rocks was said to be the voice of the spirit who dwelt there, and which the people named the Son of the Rocks. From a conversation we had with the peasantry not far from here, it seems the ancient superstition had not yet fully disappeared.”

This is precisely the notion of spirit given to rocky places elsewhere in the world, where the very echo was perceived as the ‘voice of the rocks’. Meditate on it a bit, in situ. (a fine summary of this notion and its implications — which has crept into archaeology of late — can be found in Paul Devereux’s work, Stone Age Soundtracks)

One of Brimham’s southwestern rocks was known as the Noon Stone when Mr Rooke (1787) came here. There are many stones with this name scattering Yorkshire and other northern counties, each with the same mythic background: that the sun casts a shadow from it at midday to indicate the time of day. Of this Noon Stone Mr Hooke also told us that,

“On Midsummer Eve fires are lighted on the side. Its situation is apposite for this purpose, being on the edge of a hill, commanding an extensive view. This custom is of the most remote antiquity.”

On the very southern edge of Brimham’s Rocks (some might say beyond their real border) is the Beacon Rock — and it is aptly named: as in the year 1887 on the day of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, a great beacon fire was lit here, signalling to others in the distance. Its title however, pre-dates Victoria’s Jubilee, though we don’t know how far back in time it goes…

…to be continued…

References:

- Bogg, Edmund, From Eden Vale to the Plains of York, James Miles: Leeds c.1895.

- Devereux, Paul, Stone Age Soundtracks: The Acoustic Archaeology of Ancient Sites, Vega: London 2001.

- Grainge, William, The History and Topography of Harrogate and the Forest of Knaresborough, John Russell Smith: London 1871.

- Harrison, William, A Descriptive Account of Brimham Rocks in the West Riding of Yorkshire, A. Johnson: Ripon 1846.

- Michell, John, The Earth Spirit: Its Ways, Shrines and Mysteries, Thames & Hudson: London 1975.

- Michell, John, Simulacra, Thames & Hudson: London 1979.

- Rooke, Hayman, “Some Account of the Brimham Rocks in Yorkshire,” in Archaeologia journal, volume 8, 1787.

- Speight, Harry, Nidderdale and the Garden of the Nidd, Elliot Stock: London 1894.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Nidderdale, with the Forest of Knaresborough, Elliot Stock: London 1906.

- Walbran, John Richard, A Guide to Ripon, Fountains Abbey, Harrogate, Bolton Abbey, etc, Johnson: Ripon 1856.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian