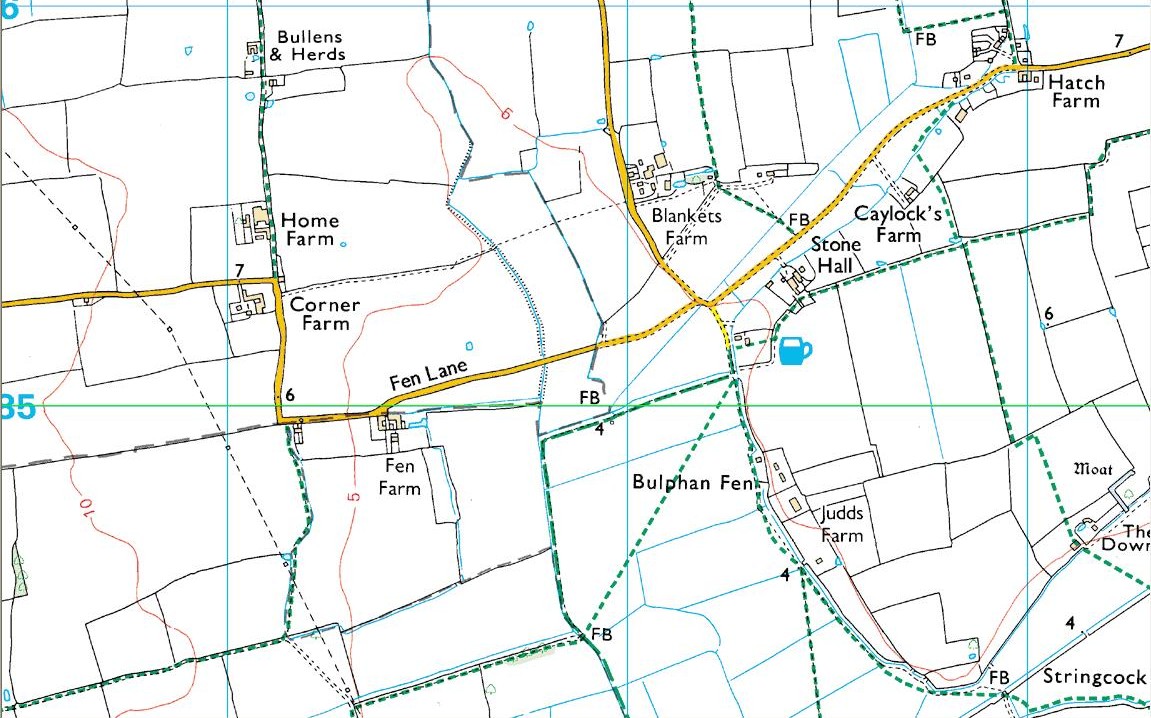

Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 98818 69839

Also Known as:

Various ways to get here: from Bathgate either take the Drumcross Road eastwards and up, or north up the Puir Wife’s Brae till you reach the crossroads where, upon the hillock north, you’ll see the old stone standing on the ridge. If you come down from Cairnpapple Hill (as most visitors are likely to do), go south for more than a mile and keep your eyes peeled in the fields to your right, shortly before the staggered crossroad. You can’t really miss it.

Archaeology & History

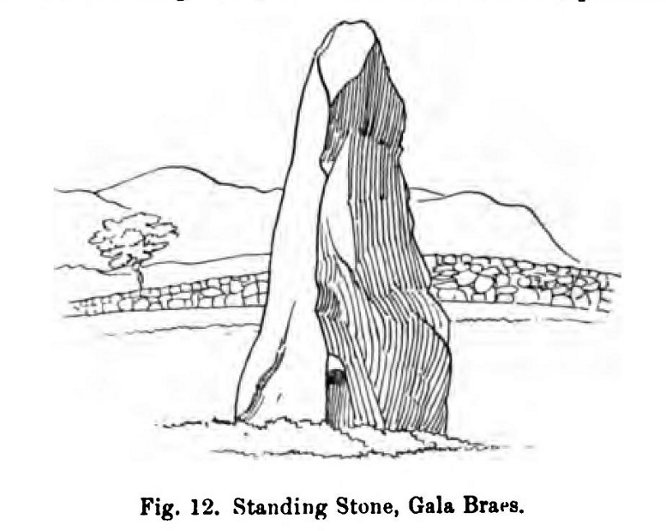

About a mile south of the superb Cairnpapple Hill, in a well-manured field at the edge of a small ridge with a vast view to the south and west, this now-solitary standing stone lives quietly and alone, gazing over its old landscape. Standing about 5½ feet tall, it seems as if the monolith has been split along its southern side at some time in the not-too-distant past, leaving a damaged wedge-shaped monolith, with one very thin eastern edge and a wider western side. The stone itself was erected to align roughly north-south-east-west.

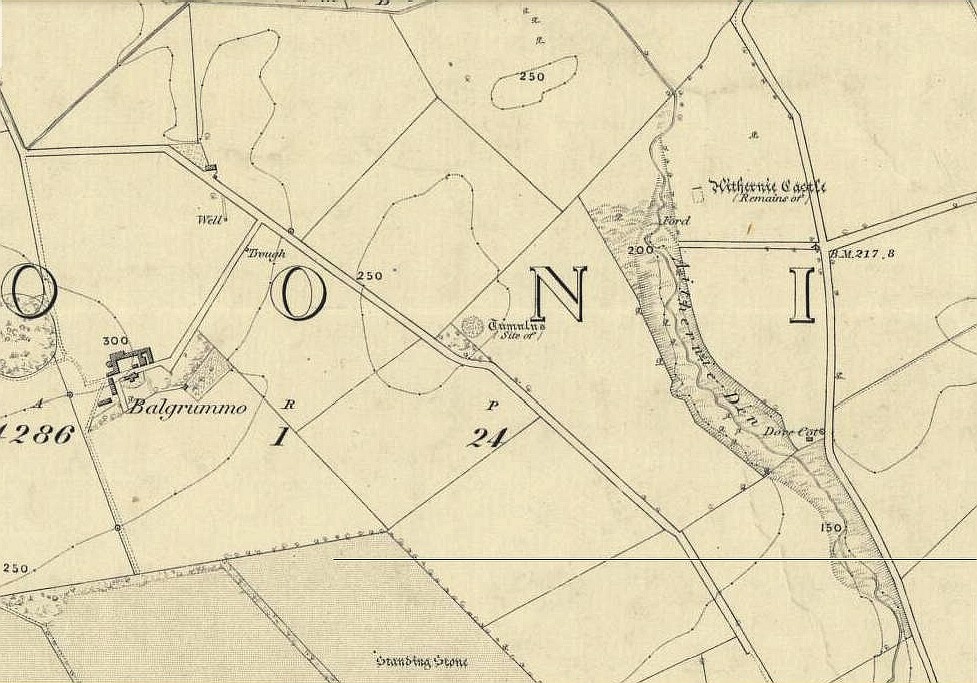

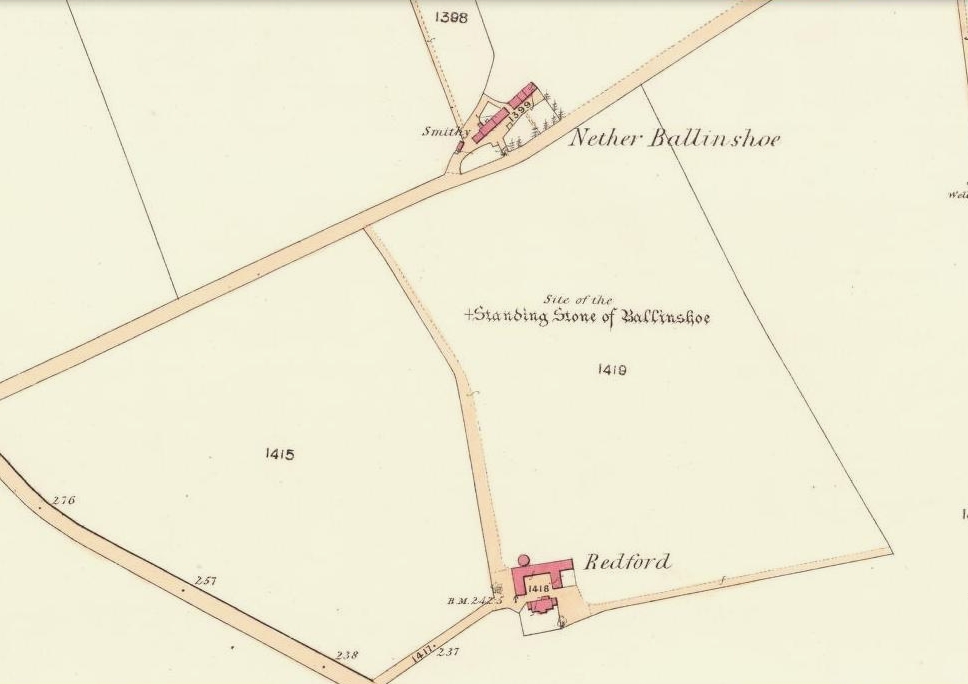

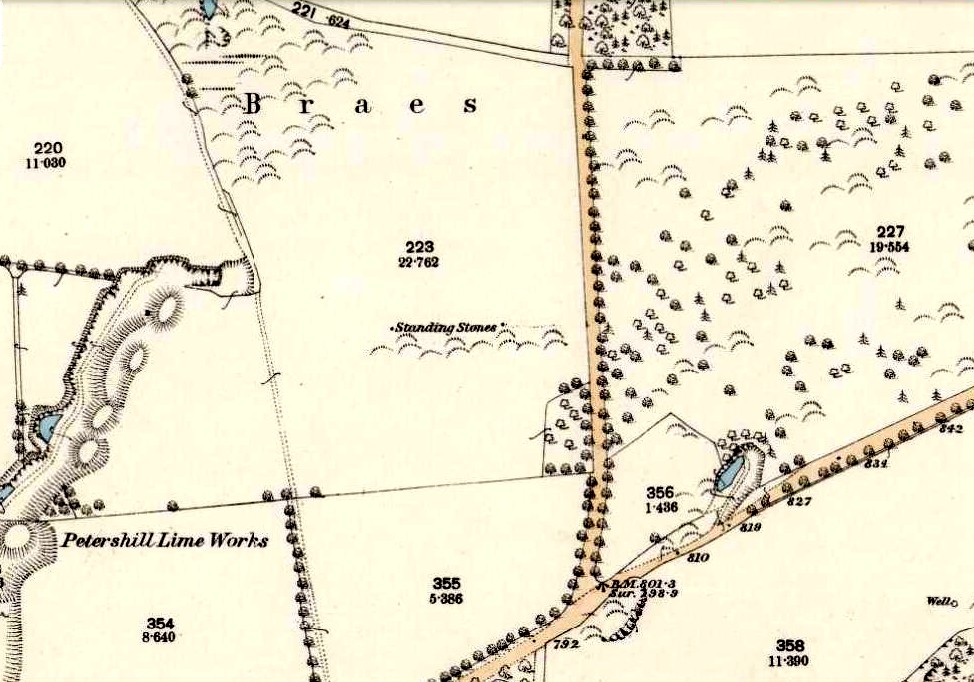

The monolith was first shown on the 1854 Ordnance Survey map of the region, along with its fallen companion (Gala Braes 2) nearly 75 yards to the west, but descriptions of the place by antiquarians are scarce. Not until Fred Coles (1903) visited here did we gain a decent account. He wrote:

“I examined this site in August 1902. It is about a mile to the east of Bathgate, and occupies the summit of a ridge extending some 300 feet westwards of the byroad that branches off due N, near the farm of Clinkingstane. The ridge is about 850 feet above sea-level. On reaching it, I found but one Standing Stone,—a rough whinstone boulder, split very unevenly, and jagged on the south side, very smooth on the two shorter sides, and girthing at the base 10 feet 5 inches. The longest edge trends WNW and ESE. It stands 5 feet 3 inches high and occupies the highest spot on the ridge.”

Whilst Mr Coles was pottering about, the courteous local farmer approached him and they began chatting about the old place—as tends to happen more than often in olde Scotland. When he,

“…asked if any digging had ever been made at either of these stones, Mr Carlaw replied that many years ago an old Bathgate worthy known as “The Apostle” persuaded his (Carlaw’s) father to dig at the base of the upper Standing Stone (the one at present erect), and they found human bones. The farm of Gala Braes has been in the tenancy of a Carlaw for upwards of a century.”

Whatever became of the old bones isn’t known. A few years later, the Royal Commission (1929) lads bimbled over to check the place out and found that it was still very much as Coles had described more than twenty years earlier, but added, “it bears no trace of sculpture.” This has since changed. Faint outlines of lettering, seemingly only a hundred years old perhaps, have been etched onto its northern face. As for the etymology of this place, Coles (1903) suggested:

“Assuming, however, that the bones found at the upper Stone were human, and taking cognisance of the fact that throughout Scotland there are many knowes, hills, hillocks and laws which are distinguished by the epithet Gallow or Gala, and that in or at many of these human remains and interments (some of them prehistoric) have been discovered, we may place this site on the Gala Braes of Bathgate in the same general group.”

Curiously he makes no mention of the nearby ‘Clinkingstane’ a few hundred yards east: an etymological curiosity that Angus MacDonald (1941) thought may have derived from a “knocking stone”; but is a word with hosts of dialect meanings, making it difficult to define with any real certainty (at the moment anyway). Just past the Clinkingstane we had the “cross on the ridge” of Drumcross—on the same ridge as our standing stones—which may well have been an attempt to keep people away from our older, more authentic heathen heritage.

The late great Alexander Thom (1990:2:341) also visited the site, but despite its impressive landscape setting and relative proximity to Gala Braes 2, he could find no astronomical orientations here. For Thom, that’s a feat in itself!

References:

- Coles, Fred, “Notices of…a Cairn and Standing Stone at Old Liston, and other Standing Stones in Midlothian and Fife,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 37, 1903.

- Grant, William (ed.), The Scottish National Dictionary – volume 3, SNDA: Edinburgh 1952.

- MacDonald, Angus, The Place-Names of West Lothian, Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh 1941.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Midlothian and Westlothian, HMSO: Edinburgh 1929.

- Thom, A., Thom, A.S. & Burl, Aubrey, Stone Rows and Standing Stones – volume 2, BAR: Oxford 1990.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian