Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 06745 45368

Getting Here

Along the B6265 old road between Keighley and Bingley, at Riddlesden go up Granby Lane, bending left into Banks Lane. About a mile up you’ll reach the moorland road. Turn left at the junction and nearly half-a-mile along there’s a layby on y’ right. From here walk along the footpath on the edge of the ridge, half-mile along bending slightly above Rough Holden Farm until, a coupla hundred yards on, you hit the dirt-track. There’s a long straight stretch of walling on your left: follow this for a few hundred yards, go through the gate and here walk on the other (left) side of the wall (if you’ve reach a derelict farm, you’ve gone too far). Some 60 yards or so down here, keep your eyes peeled on the long earthfast stone right near the walling. An alternative is to start at the steep hairpin bend up Holden Lane and follow the footpath into the woods. Walk along here (parallel with the stream below) for about 600 yards until you hit the bridge crossing the stream. Don’t cross over: instead double-back up the field on your right, go diagonally across and through the gate into the next field, and walk up along the walling to your right. 160 yards up, go through the gate and walk about 30 yards along the side of the walling again. Tis there!

Archaeology & History

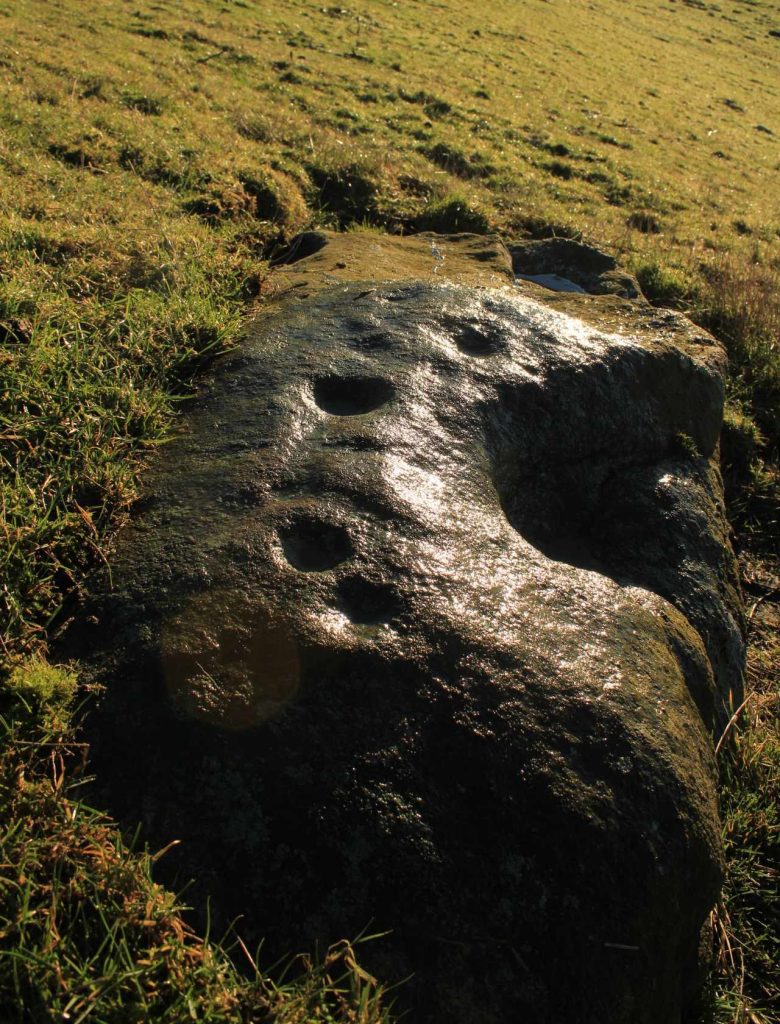

This is a fascinating carved stone on the western edge of Rombald’s Moor that I was fortunate to find in 2008. It’s found in association with two other cup-marked stones, north and south of it. I first noticed it when I was walking along the footpath by the side of the wall and saw that on a small exposed part of the rock a single cup-marking carved close to the vertical edge of the stone—and I’m glad that I stopped to give it more attention. The stone was very deeply embedded and the covering soil so tightly packed that I could only shift a small part of it—but the section that I managed to uncover and, importantly, the time of day when I did this, brought about an intriguing visage with subtle mythic overtones.

The carving was found near the end of the day just as the sun was setting and touching the far horizon. I noticed there was a cup-and-half-ring to the side of where I’d sat for a rest, near the northern edge of the stone, and the clear but soft light of the evening caught this element and almost brought it to life! As I gazed down at the half-ring, the sun highlighted it even more and I saw that some extended carved lines continued and dropped over the near vertical edge of the stone, becoming an unbroken elongated ‘ring’ that stretched twice the length of the half-ring on the flat surface. Not only that, but a faint cup-mark seemed to be inside this extended vertical ring and, as I saw this, a dreaming epiphany hit me that the symbolism behind this was a representation of the setting sun that I was watching at that very moment. It was quite beautiful and the carving seemed to come to life. The thought, nay feeling, that this part of the carving symbolized a setting sun not only slotted easily into a common animistic ingredient, but hit me as common sense too! However, as my ego and rational sense rose back to the fore (I had to get mi shit together and walk a few miles home before night fell), I saw that this impression may be a completely spurious one; but, as the rock-face inclines west, towards the setting sun, the name of Sunset Stone stuck. As I carefully fondled beneath the heavy overgrowth of vegetation covering the stone, I realised that I needed to come here again and uncover more of it, as additional cups and lines seemed to be reaching out from the mass of soil.

I returned to the stone a few times, but it was several years that I revisited the site with the intention of uncovering more of the design in the company of Richard Hirst and Paul Hornby on August 4, 2013—and it took considerable effort to roll back the turf that covered the stone. But it was worth it! For it soon became obvious that much of the stone that was covered over had been unexposed for many centuries: as Richard pointed out, the edge of the rock was very smoothed by weathering, whilst the covered section of the stone that we were revealing was still quite rough and misshapen all across the surface, lacking weather and water erosion. Much of this design therefore, highlighted itself to us as it was when the mason first carved the stone. And it turned out to be a pretty curious design!

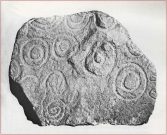

Our first impression was that the design comprised of two cup-and-rings near the middle of the rock, with another cup-and-drooping-ring near the northern edge of the stone, and between ten and twelve typical cup-markings, many on the western exposed side. But curiously near the middle were also a couple of rings whose edges had been defined, but the hollowed-out ‘cup’ in the middle remained uncut or unfinished, being a proto-ring, so to speak. Also, lines leading from these unfinished ‘cups’ were also pecked and laid out, but they were also unfinished. Some sections of the unfinished lines ran onto the western edge of the stone and were very faint, but they were undeniably there. Unfinished cups is an unusual feature for carvings on Rombald’s Moor.

But the most interesting element in the fainter, seemingly unfinished carved lines, was what may be a small spiral that started above the two faint cup-and-rings. This then continued in a sharp arc which doubled-back on itself. In the other direction, the lines curve round and go down to the vertical face of the rock, before bending back up onto the level surface again, then disappearing. The topmost cup-and-half-ring is also a curious feature. When you visit here you’ll see how this aspect of the design looks for all the world like a simply cup-and-half-ring near the edge of the stone. But, as I’ve already mentioned, closer examination shows that this “half-ring” has a larger oval body beneath it on the vertical face of the stone, very worn due to its exposure to the elements and very much in the shape of a bell—and within this large cup-and-ring ‘bell’ is a much fainter complete cup-and-ring, just below the topmost cup-marking. I know that I’ve already mentioned this, but I’m giving it added emphasis as it’s a unique design element for carvings on these moors.

The Sunset Stone really requires more attention, when the daylight conditions are just right, so that all of these intriguing aspects can be highlighted with greater lucidity. There is also the potential that more carved ingredients remains hidden beneath the compacted soil.

What seems to be a more trivial single cup-marked stone can be seen roughly 20 yards to the north.

Acknowledgements: Massive thanks to Richard Hirst of Hebden Bridge, and Prof. Paul Hornby, for their help in bringing this carving to light.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.