Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 11468 47288

Also Known as:

- Carving no.100 (Hedges)

- Carving no.228 (Boughey & Vickerman)

Come out of Ilkley/bus train station and turn right for less than 50 yards, turning left up towards White Wells. Go up here for less than 100 yards, taking your first right and walk 300 yards up Queens Road until you reach the St. Margaret’s church on the left-hand side. On the other side of the road, as well as a bench to sit on, surrounded by trees is a small enclosed bit with spiky railings with Panorama Stones 227, 228 and 229 all therein: the one in the centre being the one we’re dealing with here.

Archaeology & History

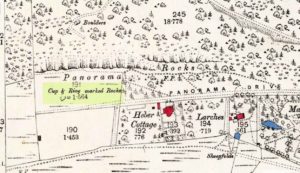

Originally located ¾-miles (1.2km) WSW of its present position in Panorama Woods (at roughly SE 10272 46995), along with its petroglyphic compatriots in this cage, the carving was moved here in 1890 when a Dr. Little—medical officer at Ben Rhydding Hydro—bought the stones for £10 from the owner of the land at Panorama Rocks, as the area in which the stones lived was due to be vandalized and destroyed. Thankfully the said Dr Little was thoughtful and as a result of his payment he had some of the stones saved and moved into their present position. However, this carving is but a fragment of its former self.

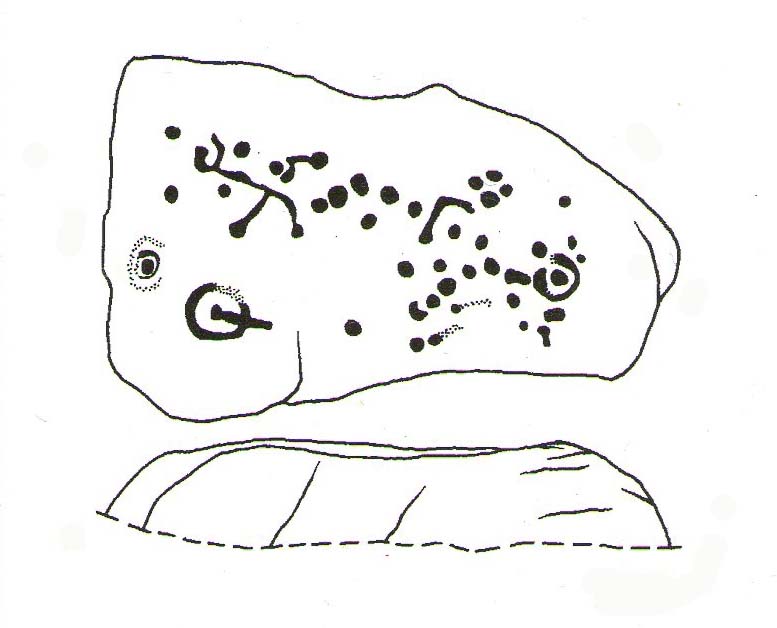

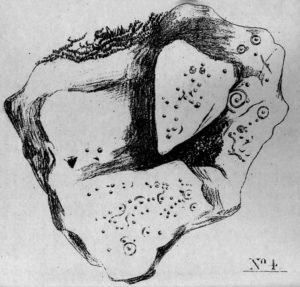

It was originally to be seen within a large prehistoric enclosure—which was completely destroyed when rich houses were built hereby, without any evaluation of the site ever being made. But particularly impressive is the fact that this now enclosed sedated stone carving was originally the large rocky base for a small rocking stone, which also had cup-markings on it and a faint cup-and-ring. This is very unusual indeed – and perhaps unique in Britain? Thankfully, several Victorian antiquarians visited and made notes and a sketch of the site before it was uprooted and a large section of it destroyed. In J. Romilly Allen’s article (1879) he told that, just a couple of yards from the more famous and ornate Panorama Stone (229), a

“second stone is of irregular shape, measuring 15ft by 12ft, and supporting a smaller stone of triangular shape 6ft long by 4ft broad. Both upper and under stone are covered with cups and rings, but the sculptures have suffered much from exposure. The superimposed rock has eleven cups, two of which are surrounded by rings. The under stone has 42 cups, nine of which have rings. Amongst these are two unusually fine examples, one has an oval cup 5in by 4in, surrounded by two rings, the diameter of the outer ring being 1ft 3in. Another has a circular cup 3in diameter, and five concentric rings, the outer ring being 1ft 5in across.”

In a sketch of the site by J. Thornton Dale done about the same time as Allen’s visit, and reproduced here (apologies for the poor quality), the “five concentric rings” that Mr Allen mentioned are not shown, but clearly a spiral design had been seen by Mr Dale’s eyes. Fascinating…. The large mass of carvings immediately left of the spiral is in fact the smaller upper stone known by modern archaeologists as carving 227.

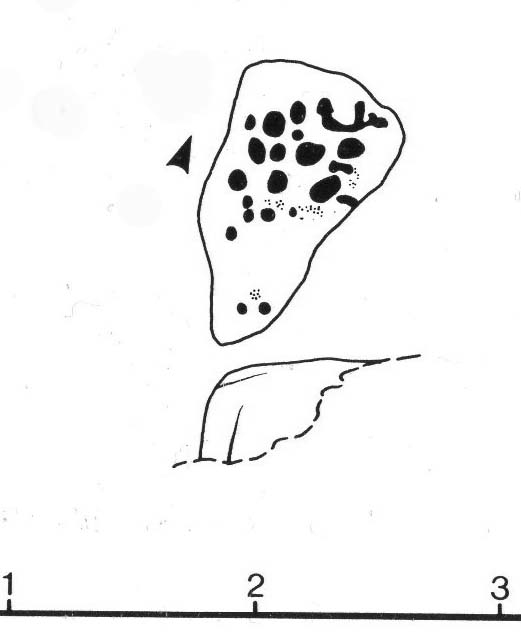

Today, all we can see of this petroglyph are two cup-and-rings, and one faint double-cup-and-ring; several incomplete rings or arcs, and at least another 30 single cup-marks, some of which have short limes running to or from them. The rest of original stone base with its other multiple rings or spiral design were obviously destroyed.

As with many of the Ilkley carvings, Boughey & Vickerman’s (2003) description barely does the stone justice. They described it simply:

“Large rock, now set in concrete base, the surface rapidly deteriorating. Over forty cups, three with single rings, one showing traces of a second, grooves.”

The mightily impressive Panorama 229 carving sits next to this one and is truly worth checking out!

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “The Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,” in Journal of British Archaeological Association, volume 35, 1879.

- Bennett, Paul, The Panorama Stones, Ilkley, TNA: Yorkshire 2012.

- Bennett, Paul, Aboriginal Rock Carvings of Ilkley and District, forthcoming.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Leeds 2003.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Downer, A.C., “Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Association,” in Leeds Mercury, August 28, 1884.

- Hadingham, Evan, Ancient Carvings in Britain, Souvenir Press: London 1974.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Heywood, Nathan, “The Cup and Ring Stones of the Panorama Rocks”, in Transactions Lancashire & Cheshire Antiquarian Society, Manchester 1889.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

Acknowledgements: With huge thanks to both Dr Stefan Maeder for help in cleaning up the stones; and to James Elkington for taking the photos and allowing ’em for use them in this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.