Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 07792 61829

Also Known as:

- Carving no.415 (Boughey & Vickerman)

Probably the easiest way is to park up at Stump Cross Caverns on the B6265 road, then walk down the road for 200 yards till you reach the track on your left running over the fields in the direction towards Simon’s Seat. Walk along the track past the Skyreholme Wall carving, where it starts going downhill and, 100 yards before you reach the fork in the tracks, look in the field on your left. The other route is to go east through Appletreewick village up to and through Skyreholme as far as you can drive, where the dirt-track begins. Keep going up till you hit the fork in the tracks. Go left, then thru the first gate you come to and walk up into the second field up where the notable rock stands out. If you can’t see it at first, look around!

Archaeology & History

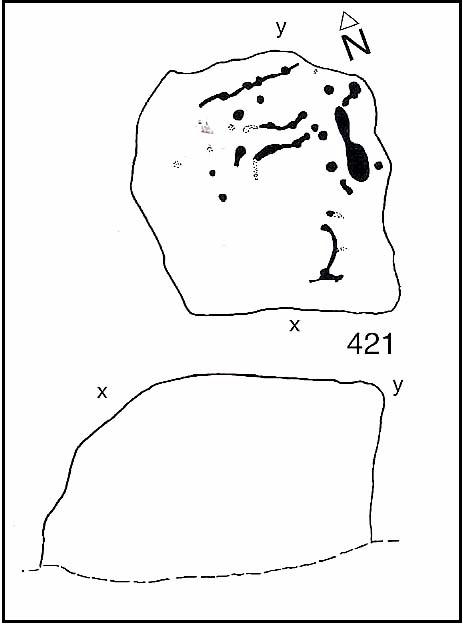

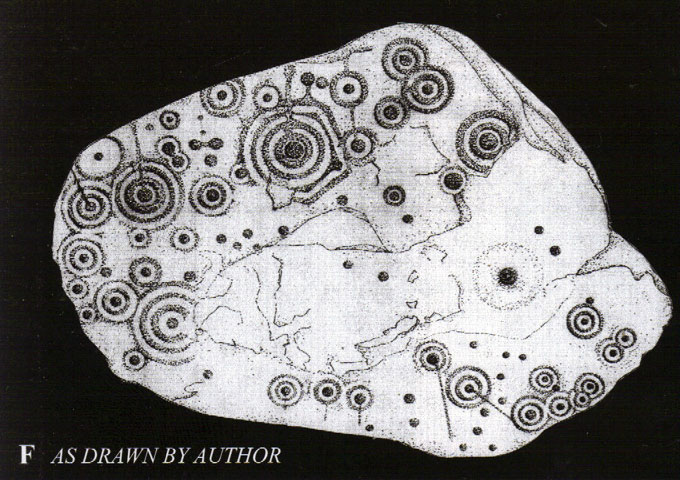

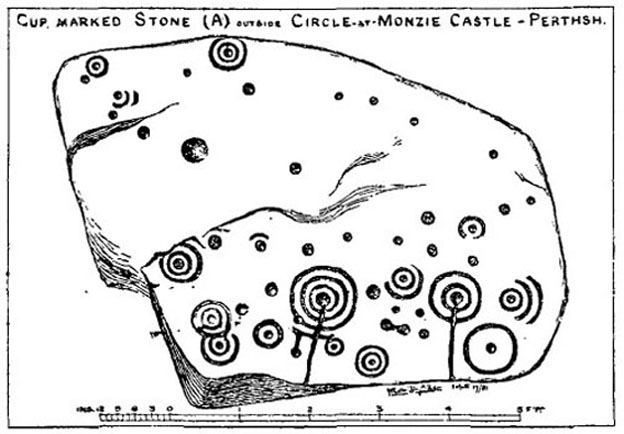

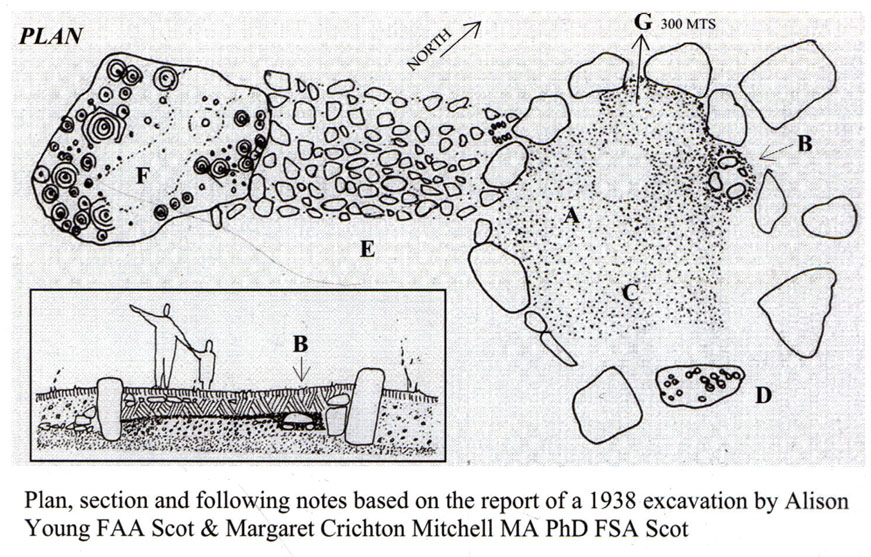

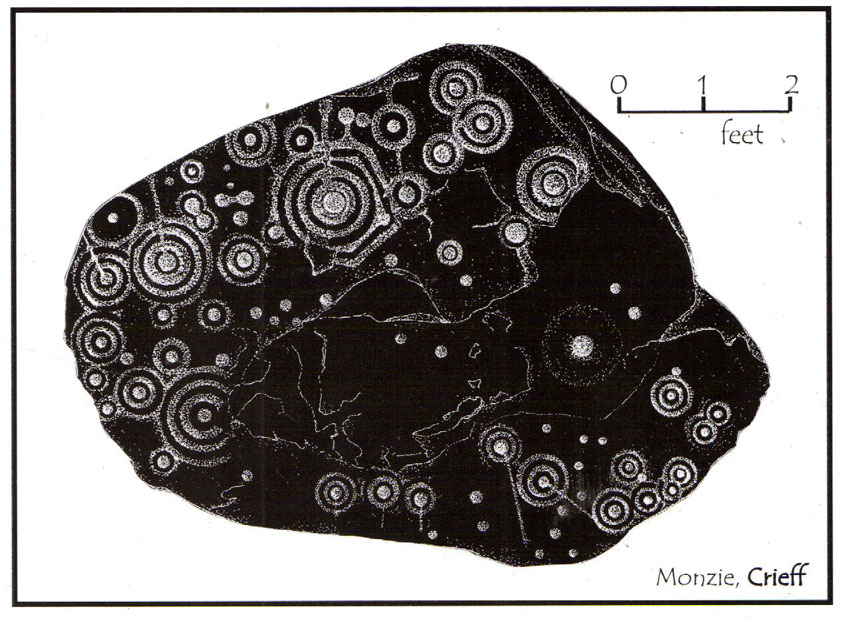

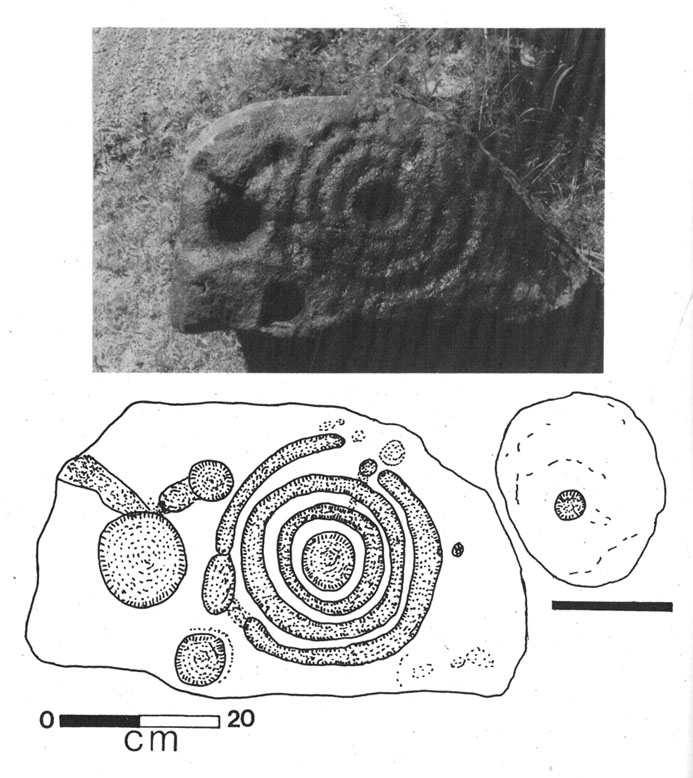

This carving was rediscovered by Stuart Feather (1964) in one of his ambles in the area — and he would have been pretty pleased when he found this one! It is the most complex and ornate of all the prehistoric carvings in and around this large open field. With at least nine cup-and-rings and more than fifty other cups etched onto its rounded upper surface, there are various other lines and grooves linking up some elements of this mythic design. The best ones are on the upright and sloping east-face of the rock, into the rising sun. In animistic terms the rock is distinctly female in nature.

Illustrated in one of Stan Beckensall’s (1999) works, the rock art students Boughey & Vickerman (2003) also include it in their survey, but give an inaccurate grid reference for the site. They nevertheless describe it as:

“Large upstanding rock with slightly domed top surface. Most of top surface decorated but weathering makes detail uncertain: over sixty cups, eight or more with rings, many grooves.”

Many other carvings can be found in the area.

References:

- Beckensall, Stan, British Prehistoric Rock Art, Tempus: Stroud 1999.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Feather, Stuart, “Appletreewick, W.R.” in ‘The Yorkshire Archaeological Register, 1963’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 41 (part 162), 1964.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Prehistoric Rock Art of Great Britain: A Survey of All Sites Bearing Motifs more Complex than Simple Cup-marks,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 55, 1989.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to the pseudonymous ‘QDanT‘ for use of the photo in this profile. Cheers Danny!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.