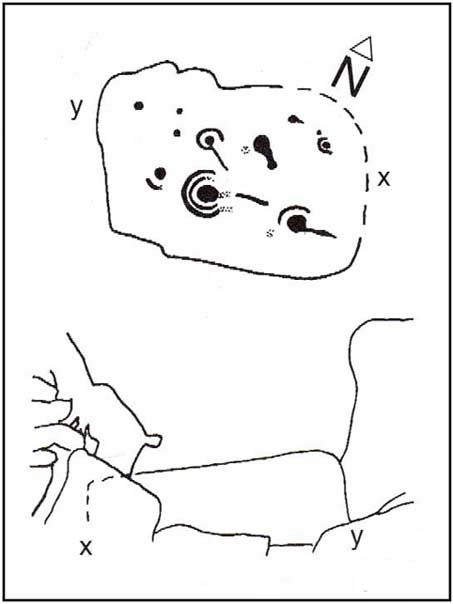

Cup-Marked Stone (lost): OS Grid Reference – ST 260 870

Archaeology & History

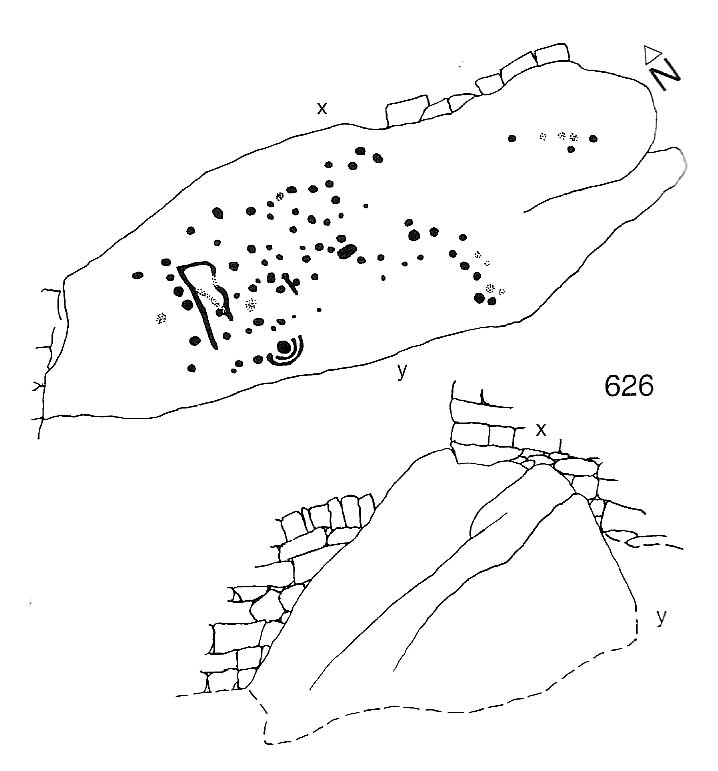

This fine-looking cup-marked stone was uncovered during a botanical outing in the last decade of the 19th century. Described as being around the township of Rhiwderin, the exact whereabouts of the carving is unknown and it’s not been seen since the first description of it in an early edition of Archaeologia Cambrensis by Mr T.H. Thomas. (1895) John Sharkey (2004) mentioned the site in his recent survey of Welsh rock art, saying simply “location unknown.”

Although we know there are no hard and fast rules for working out the location of cup-and-ring markings, one may be fortuitous in exploring any nearby Bronze Age or neolithic tombs (cairns, tumuli, etc) in the Rhiwderin district, as they do tend to enjoy the company of such sites — but I must stress, this is by no means a dead cert!

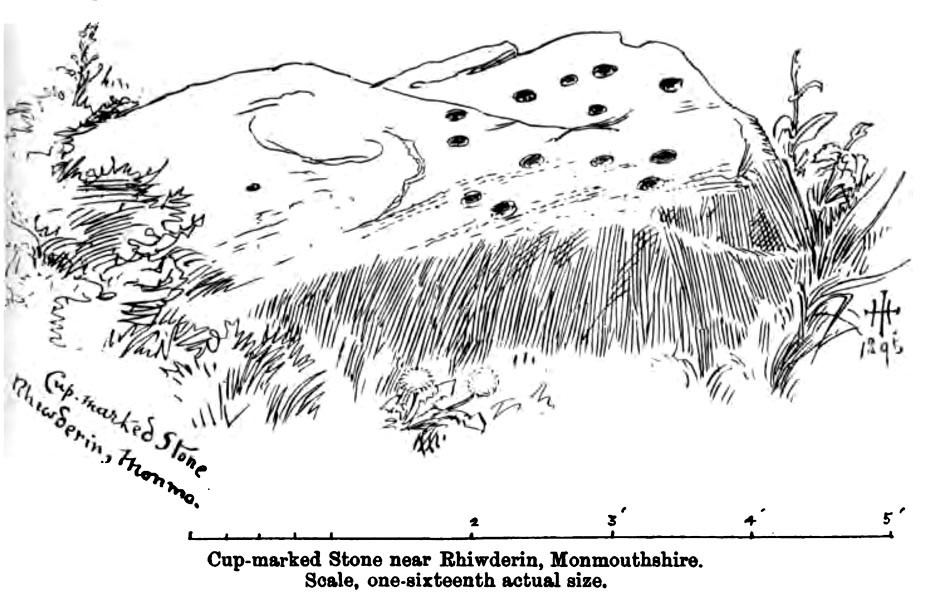

Mr Thomas’s description of the carving was as follows:

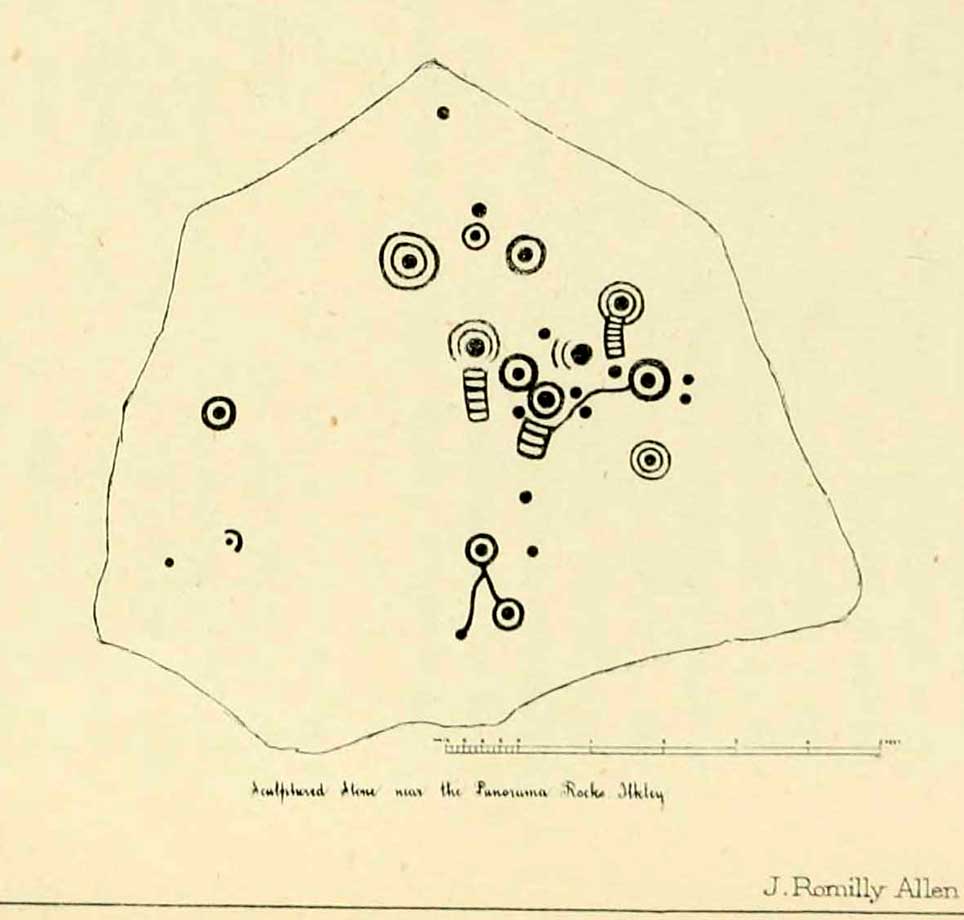

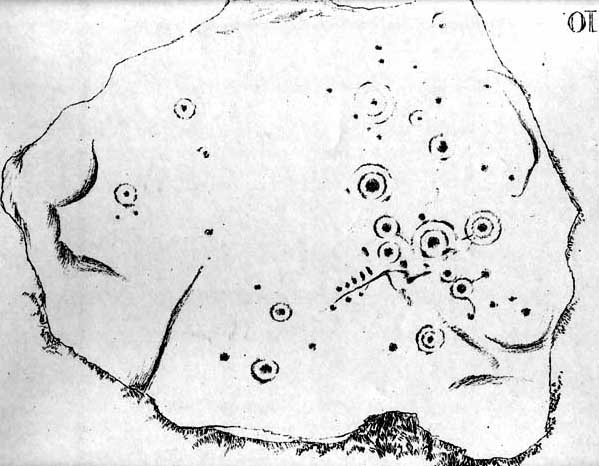

“I enclose a sketch of what seems to be a cup-marked stone which I observed yesterday near Rhiwderin, Monmouth. Unless there be some operation which simulates such markings with which I am unacquainted, I take the specimen to add an instance of these mysterious prehistoric remains to the very short list given for Wales by Mr. Romilly Allen, and to be the first reported for South Wales.

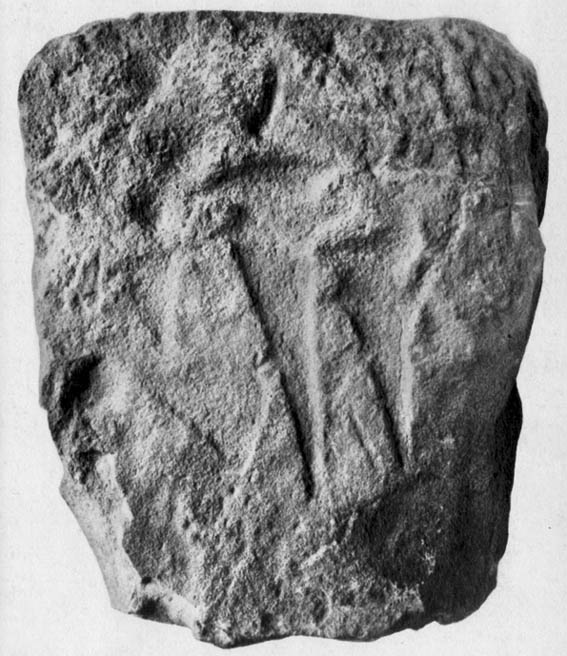

“The stone displaying the cup-markings is a mass of millstone grit, earth-fast, the slanting surface appearing above the turf being about a yard wide, and 4 feet long. Upon the upper half of the surface is a group of twelve cups from 1½ to 2in diameter, and about 1in deep. On first noticing the cups they were taken for holes out of which quartz pebbles, abundant in the local millstone grit, had been weathered, but examination of the block showed that no pebbles of large size exist, or had existed in it, and the conclusion was arrived at that the cups are artificial.

“On turning back some of the turf covering the base of the slope of the stone, no other cups were discovered.

“The stone lies within an old enclosure, as shown by wild apple-trees and an abundance of daffodils, and still more clearly by ruins, which seem those of a cottage or small farm near by. This contiguity to a habitation which does not seem to have been abandoned more than a century, made me suspect some medieval or more recent origin for the markings. I cannot, however, account for them otherwise than by supposing them to be cup-markings in the technical archaeological sense.

“The stone was observed while in the company of Dr C.T. Vachell of Cardiff, searching for varieties of narcissus which occur at several points in the neighbourhood…”

If anyone comes across this lost carving, please let us know!

References:

- Sharkey, John, The Meeting of the Tracks: Rock Art in Ancient Wales, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch: Llanrwst 2004.

- Thomas, T.H., ‘Archaeological Notes and Queries,’ in Archaeologia Cambrensis, volume 12 (5th series), 1895.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.