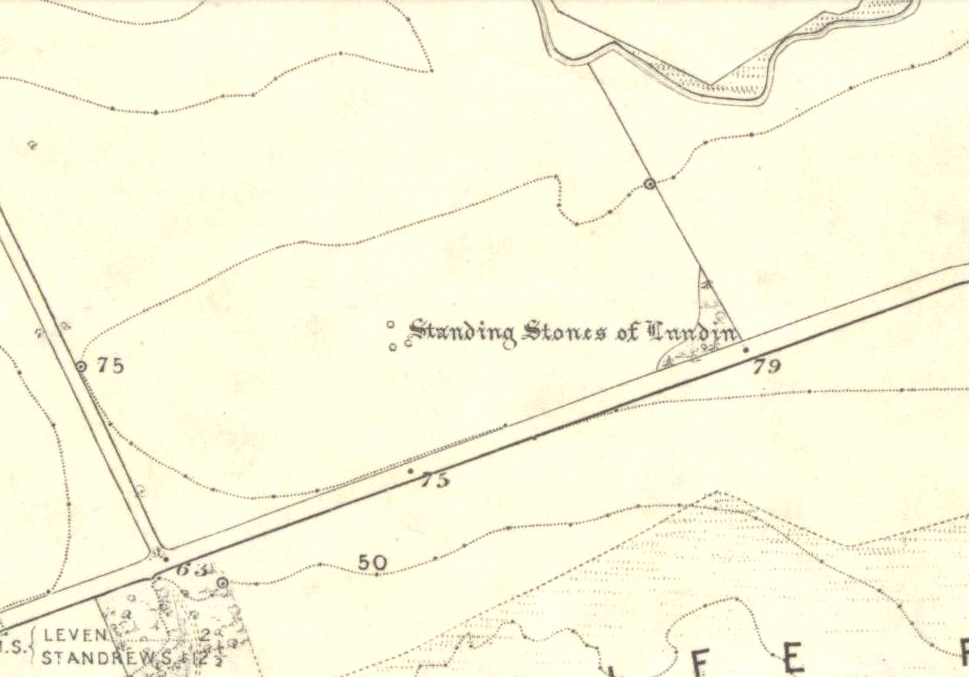

Standing Stones: OS Grid Reference – NO 4048 0272

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 32656

- Lundie Stones

- Standing Stanes of Lundy

Along the A915 coastal road from Leven to Largo, as you reach Lundin, look out for signs for the Lundin Ladies Golf Course on the left. Go there and then ask someone at the golf course if you need help; but from here you just walk west over the greens till you are ambling along the back of some houses. You can’t really miss the giant stones a couple of hundred yards ahead of you. If you somehow get lost in Lundin itself, ask a local the directions to the Lundin Ladies golf course. You can’t really go wrong.

Archaeology & History

If you like your megaliths and you venture anywhere near here, make sure you come and visit these stones. They’ll blow you away! The only downfall we have is their location—stuck on the golf course; which, of course, means that meditating here is only possible between sunfall and sunrise (though I’ve usually found that’s the best time to be at stone circles anyway!), or perhaps in the pouring rain. Whichever is your preference, these stones need looking at!

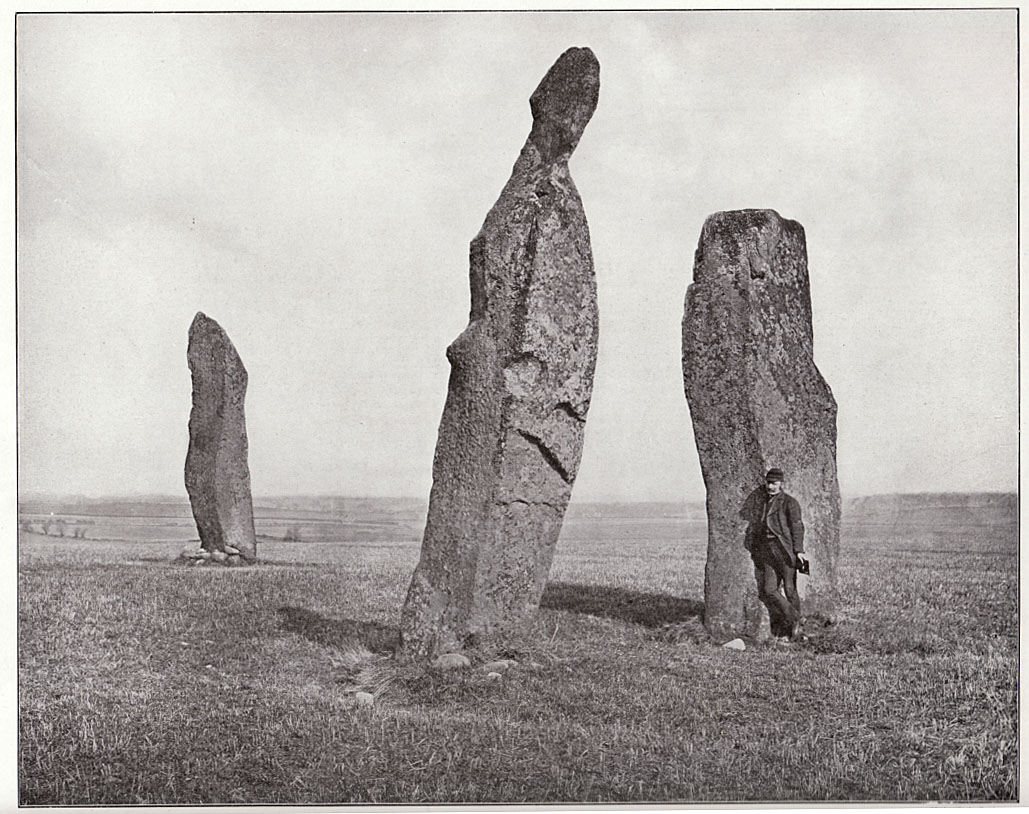

The size of them is the first thing that hits you. They belong more to the Avebury complex than sitting out on their geographical limb near the southern Fife coast. But then, that presupposes other stones of this size didn’t used to be here—and as far as I’m concerned, other giant megaliths and associated monuments must once have stood nearby. But much of the landscape hereby has been taken over by traditional agriculture and any earlier megalithic remains have seemingly been lost.

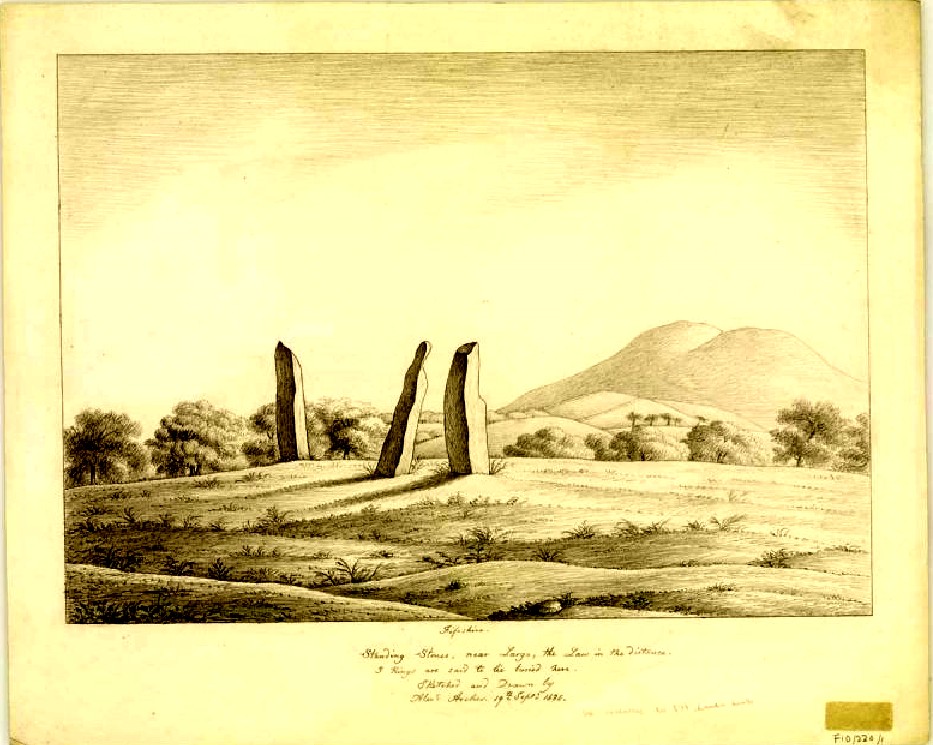

We know there were at least four stones here in the 18th century and that also, “ancient sepulchres are found near them” according to the New Statistical Account of 1837—but all remains of these burials seem to have been lost or destroyed. These facts are echoed in Leighton, Swan & Stewart’s (1840) gigantic survey. Thought by a variety of archaeological and historical sources to be the remains of a great stone circle “with a diameter of 54 feet”—it’s an assertion that I’m not too sure about myself. They are just as likely to be the remains of a great stone avenue, perhaps leading to a stone circle, long since gone, as much as any small circle of giant uprights.

In 1933, the Royal Commission survey described the size of these great red sandstone monoliths,

“Each of them has been packed at the base with a setting of small stones. Although it is not the highest, the one on the south-east, which stands with a slight inclination towards the north and the east, presents the most massive appearance. The girth at the base is 12 feet 8 inches, but measurements taken at 5 feet from the ground give the following dimensions: north face, 5 feet 2 inches; south face, 5 feet; east face, 1 foot 11 inches; west face, 2 feet 2 inches; girth, 14 feet 3 inches; and the stone becomes even wider as its height increases, until near the top where it again shrinks to a very slightly rounded extremity. The height is approximately 13 feet 6 inches. The surface is pitted by the action of the weather and shows greatest traces of decay on the east, where a crack has developed. The south stone is set with a decided inclination towards the south. It is of very irregular form with a girth at the base of 9 feet 4 inches, expanding to 10 feet at 5 feet higher up, and suddenly becoming gently attenuated at the top. The stone, which does not exhibit the same noticeable traces of weathering as the one first described, is approximately 17 feet high. The north stone, which is set with a slight inclination towards the west, appears to be still taller. It rises to a height estimated at 18 feet and has a sharply pointed top. It shows evidence of weathering at the northwest corner. Like the others, it increases in bulk from the base upwards to the middle of its height, the girth being 9 feet 6 inches at the base, and 10 feet 2 inches at 5 feet up.”

Big buggers by anyone’s estimation! Not mentioned here is the very distinct anthropomorphism, in one stone particularly—that at the southwest: a slim curvaceous body with neck and head at the top, frozen in stone no less. Surely this was intentional by the people who erected these giants? The southern pairing stand like man and wife, awaiting ceremony and customary servitude from us mere mortals. The single northern stone—whose partner was removed in the 19th century—has a similar slim stature and size, like its southwestern companion. Was its now dead partner a similar shape and stature like the southeastern stone? – another petrified pairing of man and woman? …Tis a curious feeling I have of this place…

Our megalithic magus Aubrey Burl (1988) did note the “writhing pillars” of stone here, but ventured no further with it. He did tentatively suggest (and include in his work on the subject) that the Lundin stones were one of his “four poster” circles, but thought it “impossible to prove.” He did however revise the Royal Commission measurements on the respective standing stones, informing us that,

“The NNE is the tallest, 16ft 8ins (5.1m) high, the leaning SSW stone is 15ft (4.6m) high, but the lowest, at the SSE, is also the biggest, 13ft 8ins (4.2m) tall and 6ft 5ins (2m) thick.”

He also told that there were little cairns “about 18ins (46cm) high” around the base of each standing stone when he was here in the 1980s. These were not visible when we visited in May 2013.

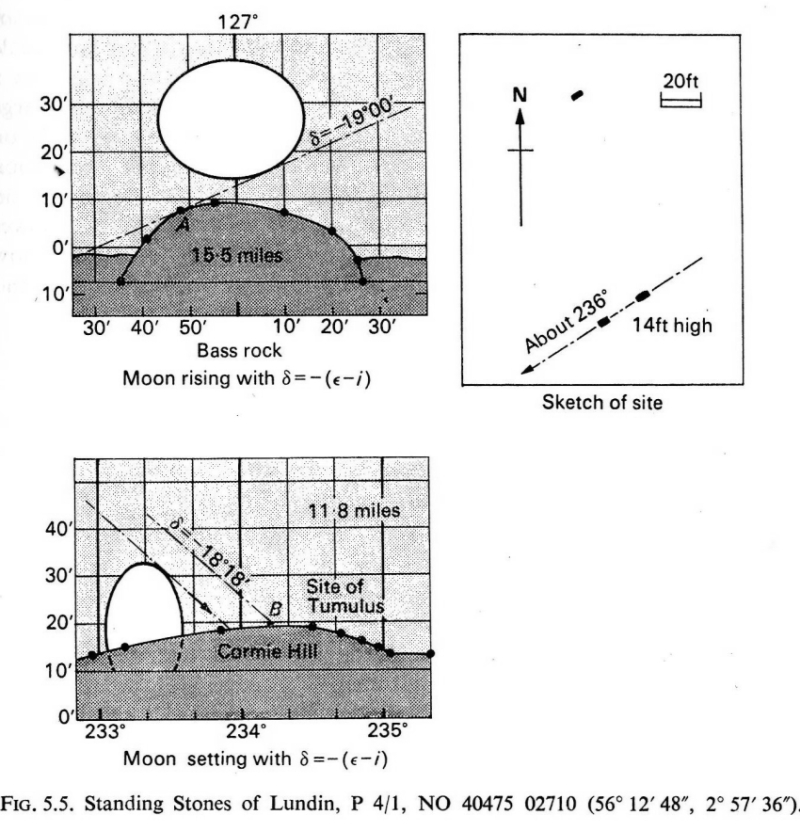

When the late great engineer and archaeoastronomer Alexander Thom (1971) came here, he found the layout of the stones to have astronomical meanings, telling:

“It was obviously an important site, so placed on flat ground that there was plenty of room for geometrical extrapolation. The alignment is seen to indicate the setting point of the Moon at the minor standstill. Trees and houses now block the view, but as the new large-scale OS maps are now available…it was possible to construct a reasonably accurate profile of Cormie Hill. In good seeing conditions, a large tumulus could have been seen on the Moon’s disc, and the tumulus shown on the Ordnance Survey happens to indicate the upper limb when the declination was -(ε-ι-Δ). When the Moon set on Cormie Hill it would rise on the Bass Rock, and we see how the stones were so placed that the lower limb just grazed the Rock when the declination was -(ε-ι).”

Thom reiterated his thoughts again in 1990, though pointed out that “the measurements should be checked” to see whether they were right. A few years earlier, Dr Douglas Heggie (1981) had done just such a thing and found the alignment seemed to be a poor one. And so it has turned out to be… Other megalithic sites however, have quite definite solar and lunar correlates in their architecture…but it seems our Lundin stones aren’t quite what Prof. Thom had hoped for.

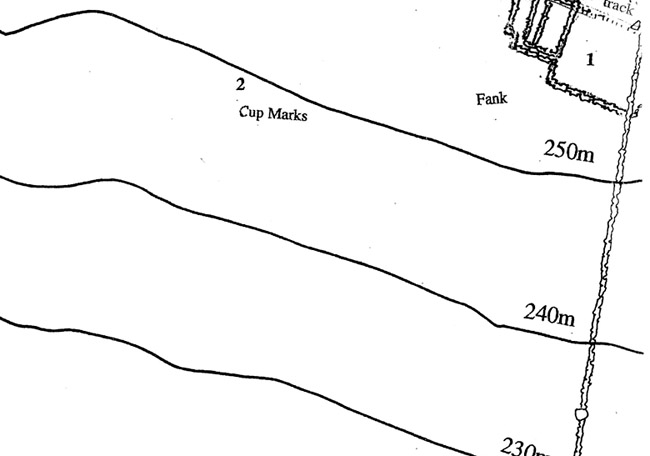

Along the eastern face of the “fattest” stone we see a number of large cup-markings, but these are all Nature’s handiwork. They were mentioned in Sir James Simpson’s (1867) early survey on the subject. However, we did see, near the base of the stone, just above ground level on its southern-face, a very distinct cup-marking with what may be the remains of a broken-ring around it. You can make it out on the photo here, but I wouldn’t stake my reputation on its legitimacy!

Folklore

Described in the Royal Commission (1933) report “as the burial stone of Danish chiefs,” this is a common tale found at other remaining megaliths along the Forth. The earliest account of this fable I’ve found is in the Edinburgh Magazine of November, 1785, where it was written:

“Various have been the conjectures as to the origin of the erection of the (stones); they are commonly known by the name of the Standing Stanes of Lundy, a seat belonging to a very old family of the name of Lundin, now to Sir William Erskine, near Largo in Fife.

“Tradition tells us, they were placed there in memory of that victory gained by Constantine II over Hubba, one of the generals of the Danish invaders, about the year 874. It is certain that battle was fought near this spot; but whether these were in memory of the action or not, I cannot determine: it is more than probable they were of a much older date.”

Legend also told that there was treasure at the stones, which was one of the reasons Daniel Wilson (1863) told the northwestern stone was broken and left only as a stump in 1792.

…to be continued…

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, Four Posters: Bronze Age Stone Circles of Western Europe, BAR 195: Oxford 1988.

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Burl, Aubrey, A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2005.

- Heggie, Douglas C., Megalithic Science: Ancient Mathematics and Astronomy in Northwest Europe, Thames & Hudson: London 1981.

- Leighton, J.M., Swan, J. & Stewart, J., History of the County of Fife – volume 3, John Swan: Glasgow 1840.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the Counties of Fife, Kinross and Clackmannan, HMSO: Edinburgh 1933.

- Ruggles, Clive, Astronomy in Prehistoric Britain and Ireland, Yale University Press 1999.

- Simpkins, John Ewart, Examples of Printed Folk-lore Concerning Fife, with some Notes on Clackmannan and Kinross-shires, Sidgwick & Jackson: London 1914.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

- Thom, Alexander, Megalithic Lunar Observatories, Oxford University Press 1971.

- Thom, A. & A.S., & Burl, Aubrey, Stone Rows and Standing Stones – volume 2, BAR 560(ii): Oxford 1990.

- Wilson, Daniel, The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland, Sutherland & Knox: Edinburgh 1863

Acknowledgements: With huge thanks to Paul Hornby, for the photos and the journey! Also a big thanks to Gill Rutter for help in clarifying “Getting there.”

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian