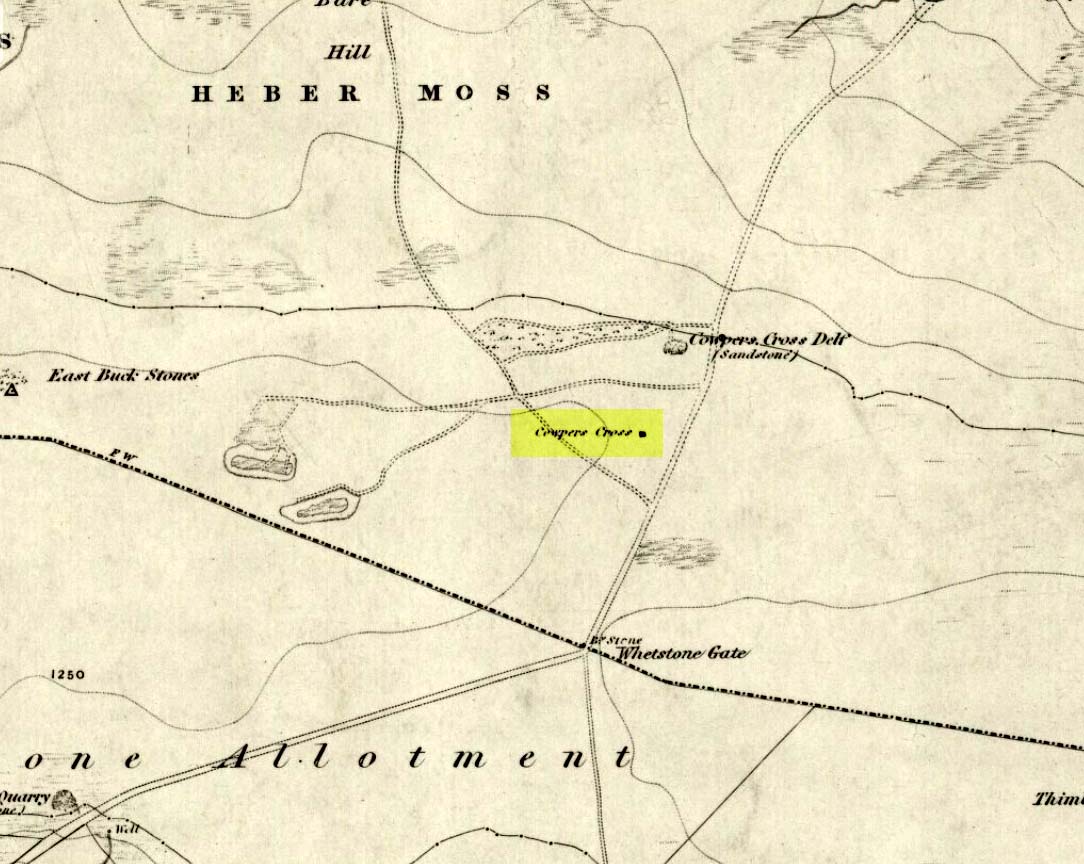

Cross: OS Grid Reference – SE 1034 4465

Also Known as:

- Black Knowle Cross

Get up to the Twin Towers right at the top of Ilkley Moor (Whetstone Gate), then walk east along the footpath, past the towers for about another 100 yards, looking out on the other side of the wall until it meets with some other walling running downhill onto Morton Moor. Follow this walling into the heather for a few hundred yards. Where it starts dropping down the slope towards the small valley, stop! From here, follow the ridge of moorland along to your left (east) and keep going till you’re looking down into the little valley proper. Along the top of this ridge if you keep your eyes peeled, you’ll find the stone cross base sitting alone, quietly…

Archaeology & History

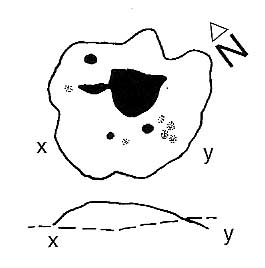

This old relic, way off any path in the middle of the moor, has little said of it. Whilst its base is still visible — standing on a geological prominence and fault line — and appears to taken the position of an older standing stone, christianised centuries ago, the site is but a shadow of its former self. When standing upright may centuries back, the “cross” was visible from many directions. We discovered this for ourselves about 20 years back, when Graeme Chappell and I sought for and located this all-but-forgotten monument. When we found the stone base, what seemed like the old stone cross lay by its side, so we repositioned it back into position on July 15, 1991. However, in the intervening years some vandal has been up there and knocked it out of position, seemingly pushing it downhill somewhere. When we visited the remains of the cross-base yesterday (i.e., Dave, Michala Potts and I) this could no longer be located. A few feet in front of the base however, was another piece of worked masonry which, it would seem, may have once been part of the same monument.

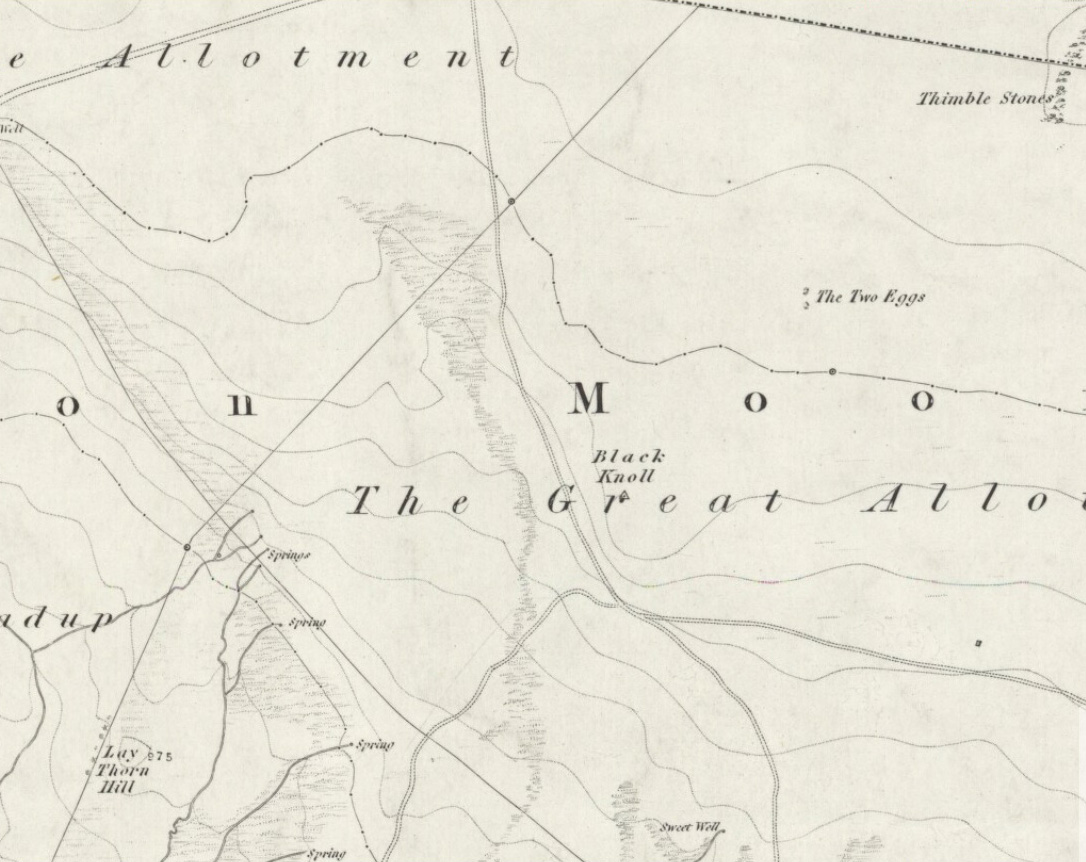

Years ago, after Graeme and I had resurrected the “cross” onto its base, I went to visit the Bradup stone circle a few weeks later and found, to my surprise, the upright stone in position right on the skyline a mile to the northeast, standing out like a sore thumb! This obviously explained its curious position, seemingly in the middle of nowhere upon a little hill. This old cross, it would seem, was stuck here to replace the siting of what seems like a chunky 3½-foot long standing stone, lying prostrate in the heather about 10 yards west of the cross base.

Stuart Feather (1960) seems to be the only fella I can find who described this lost relic, thinking it may have had some relationship with a lost road that passed in the valley below here, as evidenced by the old milestone which Gyrus and I resurrected more than 10 years back. Thankfully (amazingly!) it still stands in situ!

If you aint really into old stone crosses, I’d still recommended having a wander over to this spot, if only for the excellent views and quietude; and…if you’re the wandering type, there are some other, previously undiscovered monuments not too far away, awaiting description…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Chieveley 2001.

- Feather, Stewart, “A Cross Base on Rombald’s Moor,” in Bradford Antiquary, May 1960.

- Feather, Stewart, “Crosses near Keighley,” in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin 5:6, 1960.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian