Hillfort: OS Grid Reference – TQ 260 111

Also Known as:

- Brighton Dyke

- Poor Man’s Wall

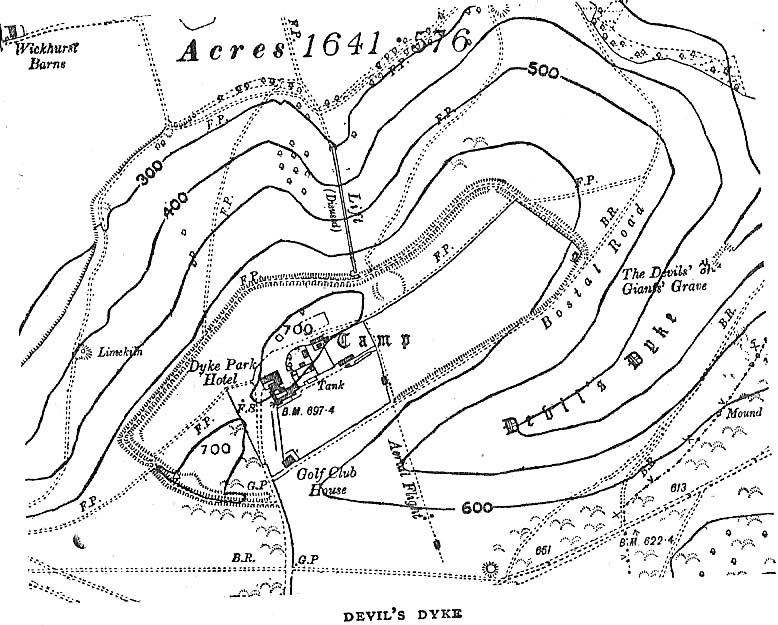

Plenty of ways of approaching this huge fella! Personally, I’d take it from the steep valley immediately east and north where the ramparts drop you down the hill, if only to get a decent idea of the scale of the thing! But those of you into taking it easy can do no better than take the country road south out of Poynings village (towards Brighton), down Saddlescombe Road, for just under a mile, where you should take a right-hand turn along the Summer Down lane for a mile. You’ll then hit the Devil’s Dyke Road. Turn right here and go to the end. You’re right in the middle of it!

Archaeology & History

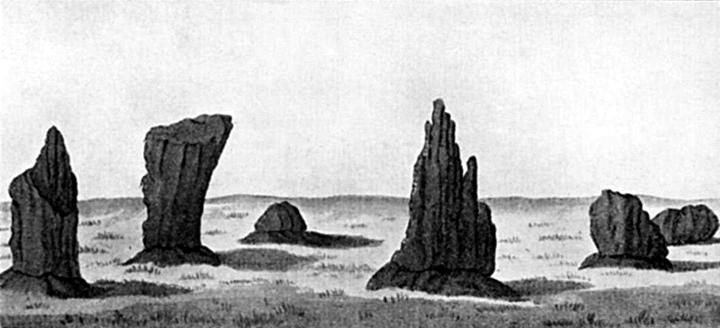

Although most of this huge monument hasn’t been given the investigation it deserves — hence making knowledge of its origins more speculative than factual — as Jacquetta Hawkes (1973) wrote, seemingly all those years ago now, “it is known that a village lying half in and round them was occupied in the Belgic period at the end of the Iron Age.” And it’s certainly big enough! The encircling circuit of dykes themselves stretch all the way round a distance of more than 2150 yards long (that’s 1.22 miles, or 1.97km!), with the longest east-west axis being more than half-a-mile across.

Nowadays it seems, the Devil’s Dyke is the name given to the steep valley below the encampment, but a hundred years back it was the camp itself that was known by this name. Described by the wandering antiquarian R. Hippisley Cox (1927) as “a camp containing forty acres (with) very steep and difficult approaches,” another early account in The Antiquaries Journal — commenting on a ground-plan of the site from the Brighton and Hove Herald of 1925 — told:

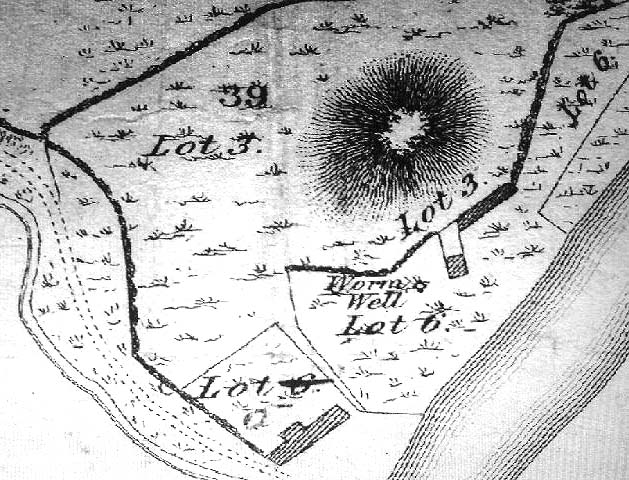

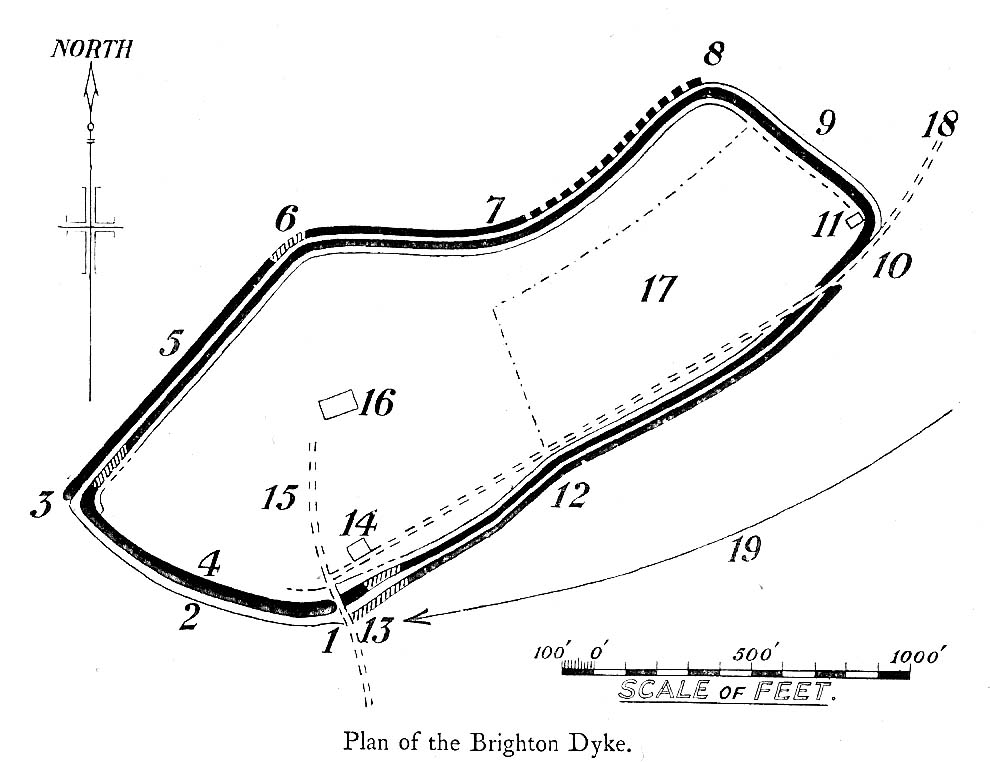

“The heavy encircling lines represent ramparts, and the thin line marks the outer margin of the accompanying ditch. A spur renders the earthwork weakest on the south-west, and the rampart is therefore highest between the points 1 and 3, rising 21ft vertically above the ditch, which is nearly filled up at the present time. On the north-west there is steep slope outside the camp, and the ramparts are considerably lower, the iner ditch being nearly obliterated. The outer rampart is now wanting betwen 7 and 8, but this inner one becomes stronger as the outer slope of the ground decreases, only to die away again on the south-east where the camp overlooks the steep Dyke Valley. A double-bank and inner ditch can still be traced from the north-east angle to a point near the old golf-club house.”

I first came here as a young lad and the site was lost on me (in them days, if monuments weren’t stiff and upright, I really didn’t see the point!). These days however, the size of it alone blows you away somewhat.

Folklore

As you’d expect the creation myths of this site and its edges relate to our old heathen friend, the devil! The landscape itself was, in old lore, the work of the devil (though prior to this, the devil was known in peasant-lore to be a legendary giant, though I am unaware of the name/s of the giant in question); and the great valley below the Devil’s Dyke encampment was actually dug out by Old Nick in the old tales. That old folklorist Jacqueline Simpson (1973) takes up the story:

“The Devil…had been infuriated by the conversion of Sussex, one of the last strongholds of paganism in England, and more particularly by the way the men of the Weald were building churches in all their villages. So he swore that he would dig right through the Downs in a single night, to let in the sea and drown them all. He started just near Poynings and dug and dug most furiously, sending great clods of earth flying left and right — one became Chanctonbury, another Cissbury, another Rackham Hill, and yet another Mount Caburn. Towards midnight, the noise he was making disturbed an old woman, who looked out to see what was going on. As soon as she understood what he was up to, she lit a candle and set it on her window-sill, holding up a sieve in front of it to make a dimly glowing globe. The Devil looked round, and thought this was the rising sun. At first he could hardly believe his eyes, but then he heard a cock crowing — for the old woman, just to make quite sure, had knocked her cockerel off his perch. So Satan flew away, leaving his work half done. Some say that as he went out over the Channel, a great dollop of earth fell from his cloven hoof, and that’s how the Isle of Wight was made; others, that he bounded straight over into Surry, where the impact of his landing formed the hollow known as his Punch Bowl.”

That’s the story anyway — take it or leave it! Of importance in this fable is the figure of the “old woman”: a much watered-down version of the cailleach figure of more ancient northern and Irish climes, where tales of her doings are still very much alive. And many are the tales of her battles with other giant figures, just as we evidently once had here.

Ghosts have been reported by local people upon this hill-top site; and there are a number of other folktales to be found here…which I’ll unfold over time as the months pass by…

References:

- Anon., “Notes: The Brighton Dyke,” in The Antiquaries Journal, 5:4, October 1925.

- Clinch, G., “Ancient Earthworks,” in Victoria County History of Sussex – volume 2 (edited by W. Page), St. Catherine’s Press: London 1905.

- Cox, R. Hippisley, The Green Roads of England, Methuen: London 1927.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta, A Guide to the Prehistoric and Roman Monuments in England and Wales, Chatto & Windus: London 1973.

- Hogg, A.H.A., “Some Aspects of Surface Fieldwork,” in The Iron Age and its Hillforts (edited by M. Jesson & David Hill), Southampton University Archaeology Society 1971.

- Simpson, Jacqueline, The Folklore of Sussex, Batsford: London 1973.

- Simpson, Jacqueline, “Sussex Local Legends,” in Folklore Journal, volume 84, 1973.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.