Stone Circle (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NO 5871 7189

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

When the Ordnance Survey lads visited this area in 1860, they stood upon this small knoll that was known as Torrnacloch – or the Knoll of the Stone. They were informed that a ring of stones had stood here, but had been destroyed about 1840, apparently by a local farmer. The stones were described as being about 3 feet high. They subsequently added it on the earliest OS-map of the area, but also made note that a cist was found within the site. The circle was included and classed as a stone circle in Aubrey Burl’s (2000) magnum opus, but had previously been classed as a cairn with “a kerb of large boulders” by the Royal Commission doods. (1983) They based their assessment on the appearance of some of the stones found on a gravel mound behind the farm which had apparently been removed from the circle when it was destroyed. Andrew Jervise (1853) gave us the following account:

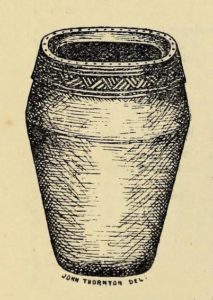

“The Chapelry of Dalbog was on the east side of the parish, due west of Neudos. The time of its suppression is unknown; and though no vestige of any house remains, the site of the place of worship is still called the “chapel kirk shed” by old people, and, in the memory of an aged informant, a fine well and hamlet of houses graced the spot. This field adjoins the hillock of Turnacloch, or “the knoll of stones,” which was probably so named, from being topped in old times by a so-called Druidical circle, the last of the boulders of which were only removed in 1840. Some of them decorate a gravel mound behind the farm house; and, on levelling the knoll on which they stood, a small sepulchral chamber was discovered, about four feet below the surface. The sides, ends, and bottom, were built of round ordinary sized whinstones, cemented with clay, and the top composed of large rude flags. It was situate on the sunny side of the knoll, within the range of the circle; but was so filled with gravel, that although carefully searched, no relics were found.”

The emphasis on this place being where a stone circle stood is highlighted in the place-name Torrnacloch, or the hillock of stones/boulders. Both Dorwood (2001) and Will (1963), each telling it to be where a stone circle stood; with Will adding that parts of the circle “may yet be seen in rear of the steading of Dalbog.” If this had been where a cairn existed, some variant on the word carn would have been here.

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Dorwood, David, The Glens of Angus, Pinkfoot: Balgavies 2001.

- Jervise, Anrew, The History and Traditions of the Land of the Lindsays in Angus and Mearns, Sutherland & Knox: Edinburgh 1853.

- MacLaren, A. et al, The Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Central Angus, RCAHMS: Edinburgh 1983.

- Will, C.P., Place Names of Northeast Angus, Herald: Arbroath 1963.

Acknowledgements: Big thanks for use of the 1st edition OS-map in this site profile, Reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian