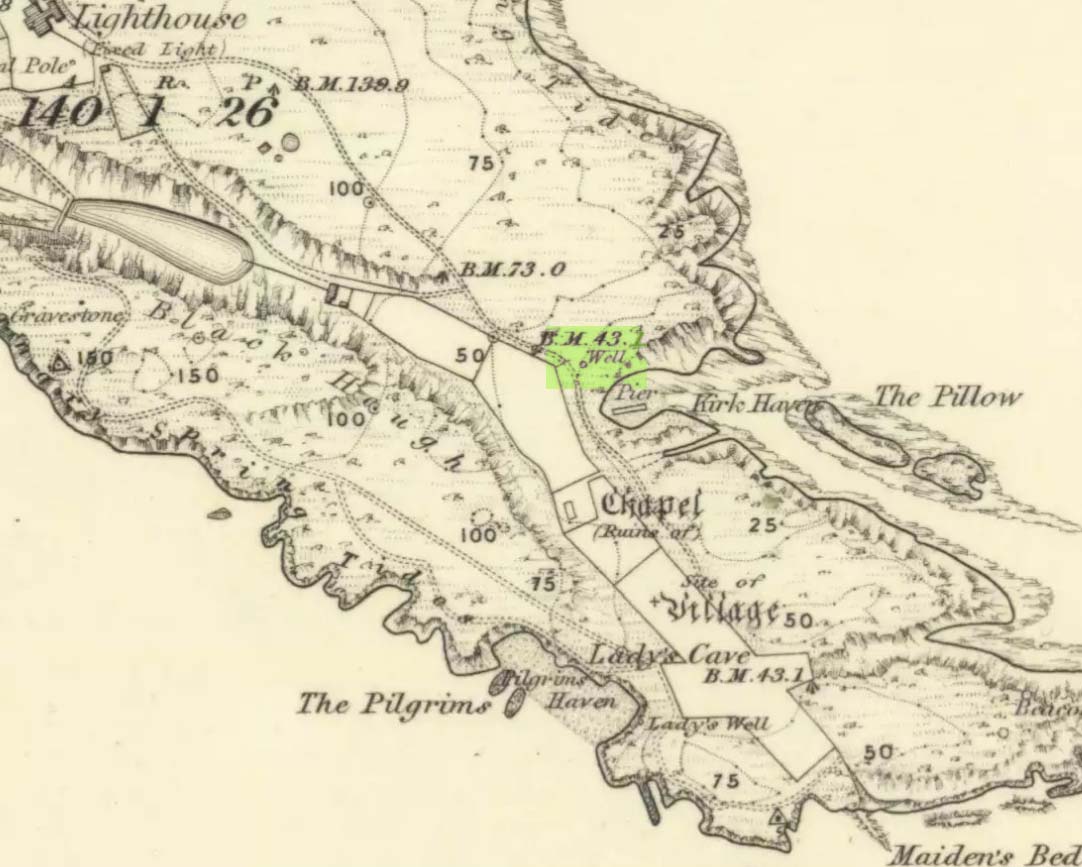

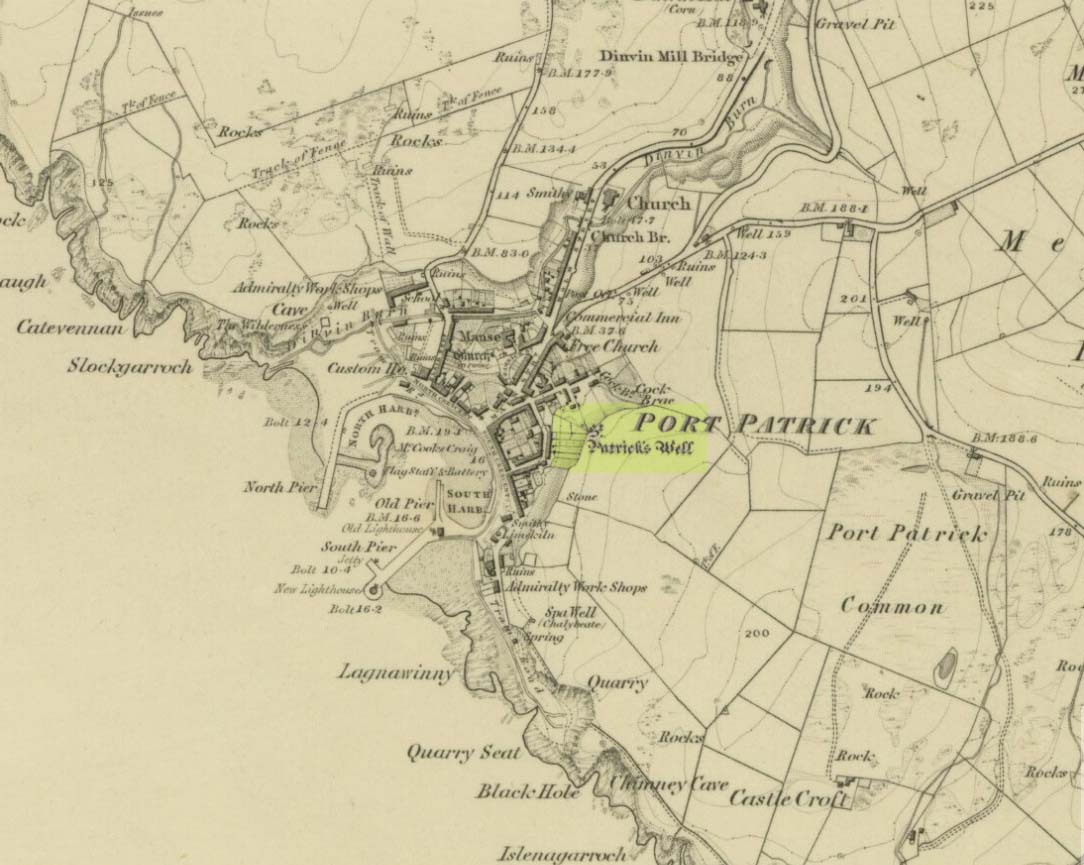

Holy Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – TQ 3096 8106

Archaeology & History

Close to the long-lost Strand Cross and long-lost Strand Maypole, in bygone centuries was also to be found a holy well of great repute, dedicated by early christians to the sea-faring St. Clement. Its presence was recorded in the ‘Holywell Street’ name at far the eastern end of The Strand but, like its compatriot monuments, it too is long-lost… Thankfully we have reasonably good accounts of its existence, although its precise whereabouts has been something of a matter of debate.

The site is certainly of considerable antiquity, as evidenced in the early citations of the street-name ‘Holywell Street’. The earliest reference is found in legal records from 1373, where it was described as “viam regiam que vocatur Holeway“, or “the main road which is called the Holy way.” Several other references name the street as ‘Holwey’ and ‘Holewlane’, before it became shown as ‘Holliwell Street’ on the 1677 “Large and Accurate Map of the city of London” (I can find no copy of this on-line that allows for a reproduction of it on here, sadly). The following year, William Morgan cited it as being ‘Hollowell street’, but curiously the place-name writers Gover, Mawer & Stenton (1942) opted that the name derives from it being a ‘hollow way’ and not relate it to the holy well which we know was located at the far eastern end of the now-missing Holywell Street. I think they gorrit wrong on this occasion!

The best historical narrative of the site is undoubtedly that by Alfred Foord (1910), whose lengthy research waded through all the possible locations of the site, concluding in the Appendix of his work that, “in front of Clement’s Inn Hall…was the far-famed ‘holy well’ of St. Clement.” It’s best leaving Mr Foord to do all the talking on this one:

“The earliest mention of the well of St. Clement was made by the Anglo-Norman chronicler, FitzStephen, in his History of London, prefixed to his Life of Becket (written between the years 1180 and 1182), where in the oft-quoted passage, he describes the water as “sweete, wholesome, and cleere,” and the spot as being ”much frequented by scholars and youths of the Citie in summer evenings, when they walk forth to take the aire.”

“Turning to Stow (1598), a fairly correct idea of the position of the holy well may be formed from his remarks. Referring to Clement’s Inn, he defines it as “an Inne of Chancerie, so called because it standeth near St. Clement’s Church, but nearer to the faire fountain called Clement’s Well.” As to its condition at the time he wrote, he says: “It is yet faire and curbed square with hard stone, and is always kept clean for common use. It is always full and never wanteth water.” Seymour writes of it in his Survey of London (1734-35) as “St. Clement’s pump, or well, of note for its excellent spring water.” Maitland (1756) says of it: “The well is now covered, and a pump placed therein on the east side of Clement’s Inn and lower end of St. Clement’s Lane.” This appears to be the first specific reference to the change from a draw-well to a pump. Hughson (1806-09), and Allen (1827-29) both allude briefly to the well, but the following authors say nothing about it : Northouck, A New History of London (1773); Pennant, Some Account of London (1790 and 1793); Malcolm, Londinium Redivivum (1803-07); and Riley, Memorials of London and London Life in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Centuries (1868).

“Among the more modern writers, John Sanders in his “Strand” article, published in Knight’s London (1842), says: “The well is now covered with a pump, but there still remains the spring, flowing as steadily and freshly as ever.”

“George Emerson (1862), in speaking of the Church, says: ”It stood near a celebrated well, which for centuries was a favourite resort for Londoners. The water was slightly medicinal, and having effected some cures, the name Holy Well was applied.”

“John Diprose, an old inhabitant of the parish of St. Clement Danes, in his account of the parish (published in two volumes in 1868 and 1876), has this passage on the subject: “It has been suggested that the Holy Well was situated on the side of the Churchyard (of St. Clement), facing Temple Bar, for here may be seen a stone-built house, looking like a burial vault above ground, which an inscription informs us was erected in 1839, to prevent people using a pump that the inhabitants had put up in 1807 over a remarkable well, which is 191 feet deep, with 150 feet of water in it. Perhaps this may be the ‘holy well’ of bygone days, that gave the name to a street adjoining.” Timbs says in his Curiosities of London (1853), “the holy well is stated to be that under the ‘Old Dog’ tavern, No. 24, Holywell Street.” Mr. Parry, an optician in that street, and an old inhabitant, held the same opinion. Mr. Diprose, on the other hand, finds “upon examination, no reason for supposing that the holy well was under the Old Dog tavern, there being much older wells near the spot.” Other inhabitants believe that the ancient well was adjacent to Lyon’s Inn, which faced Newcastle Street, between Wych Street and Holywell Street. In the Times of May 1, 1874, may be found the following paragraph, which reads like a requiem: “Another relic of Old London has lately passed away; the holy well of St. Clement, on the north of St. Clement Danes Church, has been filled in and covered over with earth and rubble, in order to form part of the foundation of the Law Courts of the future.” On the 3rd of September of the same year (1874) the Standard refers to this supposed choking up of the old well, and suggests that “there had been a mis-apprehension, for the well, instead of being choked up, was delivering into the main drainage of London something like 30,000 gallons of water daily of exquisite purity. This flow of water which wells up from the low-lying chalk through a fault in the London Clay, will be utilised for the new Law Courts.” A contributor to Notes and Queries (9th series, July 29, 1899) draws attention to the following particulars from a correspondent, a Mr. J. C. Asten, in the Morning Herald of July 5, 1899: “Having lived at No. 273, Strand, for thirty years from 1858, it may interest your readers to know that at the back of No. 274, between that house and Holy Well Street, there exists an old well, which most probably is the ‘Holy Well.’ It is now built over. I and others have frequently drunk the exceedingly cool, bright water. There was an abundance of it, for in the later years a steam-printer used it to fill his boilers.” An interesting account of another well, less likely, however, to be the true well, is given by the late Mr. G. A. Sala in Things I have Seen and People I have Met (1894), who describes the clearing of the well which was not under, but behind the ‘Old Dog,’ in Holy Well Street, where he resided for some months about 1840. One or two interesting things turned up, amongst them being a broken punch bowl, having a William and Mary guinea inserted at the bottom ; a scrap of paper with the words in faded ink, “Oliver Goldsmith, 13s. 10d.,” perhaps a tavern score, and a variety of other articles.

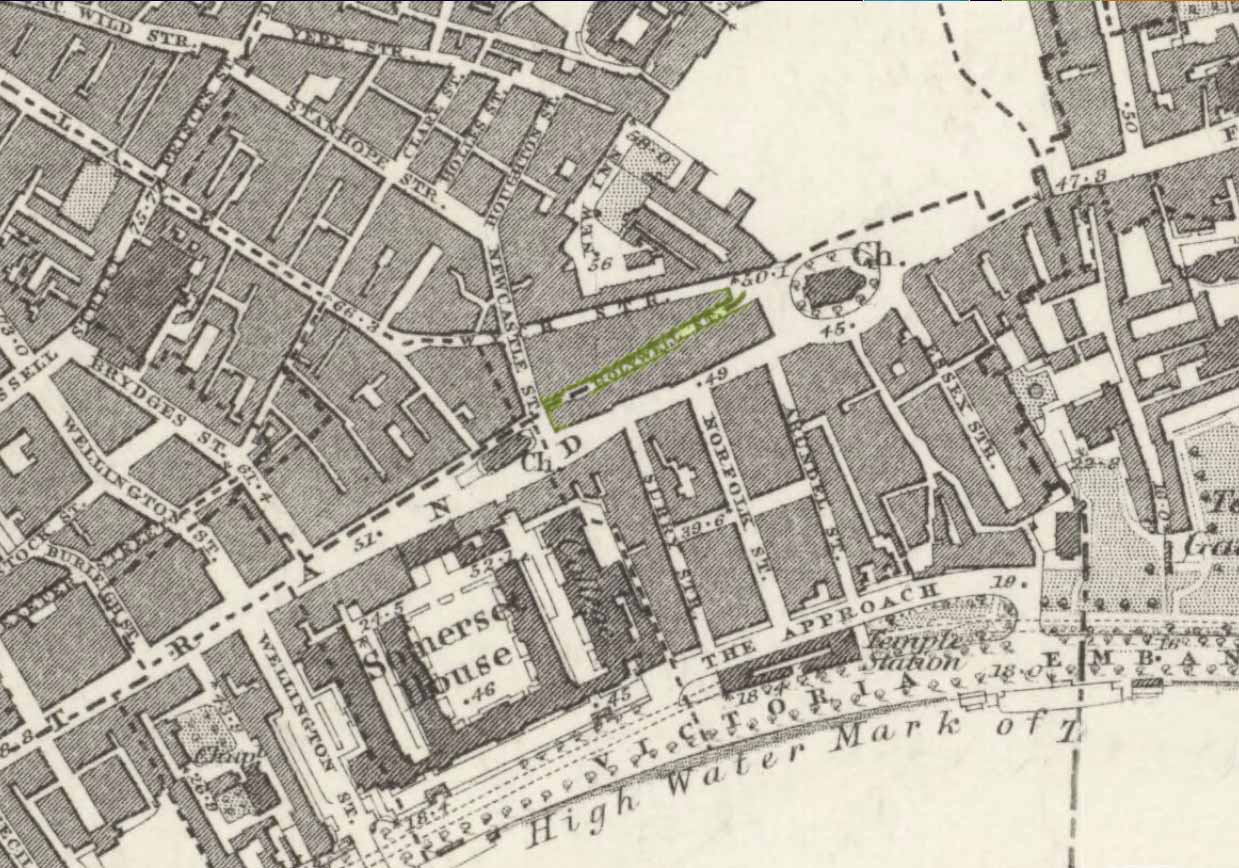

“The erection of the new Law Courts—1874-82—which, with the piece of garden ground on the western side, cover a space of nearly 8 acres, swept away numbers of squalid courts, alleys, and houses, including a portion of Clement’s Inn, where the well was. Further west another large area was denuded of houses, by which Holywell Street—demolished in 1901—and nearly the whole of Wych Street (a few houses on its northern side only being left), have been wiped off the map.

“In order, if possible, to obtain some corroboration of the Standard‘s statement that the spring existed in 1874, the writer applied for information on the point to the Clerk of Works 2 at the Royal Courts of Justice, who wrote that he could find no trace of St. Clement’s Well, so that the report in the Times (quoted above) is probably correct. The water-supply to the Courts of Justice, he adds in his letter of June 13, 1907, is from the Water Board’s mains, and an underground tank, used for the steam-engine boilers, situated between the principal and east blocks, is filled partly from the roofs and partly from shallow wells in the north (Carey Street) area of the building—the overflow running into the drains.

“On the Ordnance Survey Map, published in 1874, a spot is marked on the open space west of the Law Courts with the words “Site of St. Clement’s Well”: this spot is distant about 200 feet north from the Church of St. Clement Danes, and about 90 feet east of Clement’s Inn Hall, which was then standing. The Inn, with the ground attached to it, was disposed of not long after 1884, when the Society of Clement’s Inn had been disestablished.”

On the northeast side of the St. Clement’s church, a metal plaque was erected in 1807 (it’s still there!) which claims to be the position where the holy well existed. It reads:

“The well underneath, 191 feet deep, and containing 150 of water was sunk & this pump erected at the expense of the parish of St Clement Danes.”

In Mr Sunderland’s (1915) account of the Well, he told that it was located “200ft north” of the church, “covered by the Law Courts, built between 1874 and 1882”; and that although the waters here were clear and pure, they were “probably not medicinal”. Its waters, he said, fed the old Roman Spring Bath at No.5, The Strand.

In Edward Walford’s (1878) standard work, he told that,

“Round this holy well, in the early Christian era, newly-baptised converts clad in white robes were wont to assemble to commemorate Ascension Day and Whitsuntide; and in later times, after the murder of Thomas à Becket had made Canterbury the constant resort of pilgrims from all parts of England, the holy well of St. Clement was a favourite halting-place of the pious cavalcades for rest and refreshment.”

Folklore

Although I can find nothing specifically relating St. Clement’s Well with the old customs cited below, a connection seems highly likely, as the events started where Mr Foord (1910) said the holy well was located. The great english folklorist Christina Hole (1950) wrote:

“One of the most charming ceremonies in London is the Oranges and Lemons service at St. Clements Danes. It takes place every year on March 31st, or as near as possible to that date, and is a modified revival of an old custom which has only recently died out. In the lifetime of many elderly people now living, the attendants of Clements Inn used annually to visit all the residents of the Inn and present them with oranges and lemons, receiving some small gift in return. At the March service, the church is decorated with oranges and lemons, and all the children who attend are given fruit as they leave the building, while the bells play the old nursery rhyme. The oranges and lemons are supplied by the Danish colony in London, whose church this has been for many centuries, and are often distributed by Danish children wearing their national colours of red and white.”

The historian Laurence Gomme (1912) propounded that the ancient stone cross of The Strand nearby, and the Strand maypole, were elements relating to an unbroken line of heathen traditions dating back to the early Saxon period—and the customs here cited would seem to increasingly validate this. A more detailed multidisciplinary analysis of this cluster of sites along The Strand by competent occult historians is long overdue.

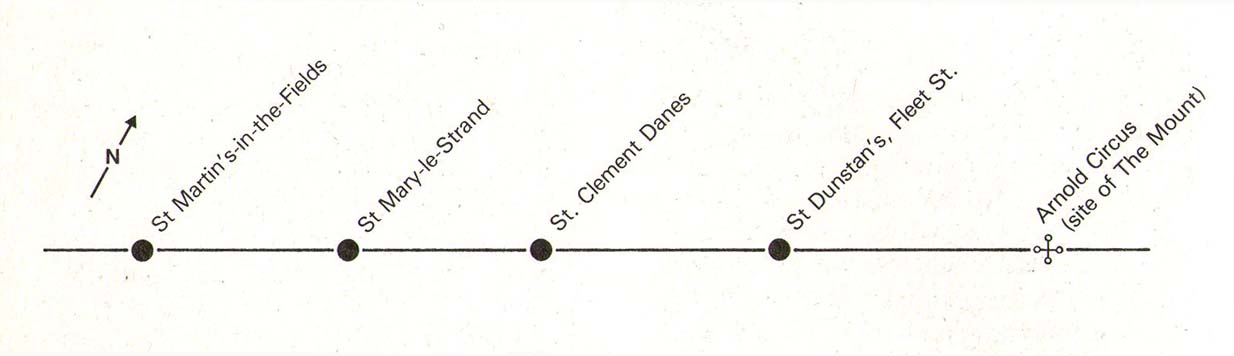

One final thing: if the position of the Well is indeed the one cited on the 1807 plaque, to the northeast of St. Clement’s church, then it lies bang on the ley-line that was first propounded by Alfred Watkins (1922; 1925; 1927), and subsequently enlarged upon by Devereux & Thompson! (1979)

References:

- Devereux, Paul & Thomson, Ian, The Ley Hunter’s Companion, Thames & Hudson: London 1979.

- Foord, Alfred Stanley, Springs, Streams and Spas of London: History and Association, T. Fisher Unwin: London 1910.

- Gomme, Laurence, The Making of London, Clarendon: Oxford 1912.

- Gover, J.E.B., Mawer, Allen & Stenton, F.M., The Place-Names of Middlesex, Cambridge University Press 1942.

- Hole, Christina, English Custom and Usage, Batsford: London 1950.

- Johnson, Walter, Byways in British Archaeology, Cambridge University Press 1912.

- Street, Christopher E., London’s Ley Lines, Earthstars: London 2010.

- Sunderland, Septimus, Old London Spas, Baths and Wells, John Bale: London 1915.

- Walford, Edward, Old and New London – volume 3, Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1878.

- Watkins, Alfred, Early British Trackways, Motas, Mounds, Camps and Sites, Watkins Meter: Hereford 1922.

- Watkins, Alfred, The Old Straight Track, Methuen: London 1925.

- Watkins, Alfred, The Ley Hunter’s Manual, Simpkin Marshall: London 1927.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

This is the first detailed guide ever written on the holy wells and healing springs in and around the ancient city of Edinburgh, Scotland. Written in a simple A-Z gazetteer style, nearly 70 individual sites are described, each with their grid-reference location, history, folklore and medicinal properties where known. Although a number them have long since fallen prey to the expanse of Industrialism, many sites can still be visited by the modern historian, pilgrim, christian, pagan or tourist.

This is the first detailed guide ever written on the holy wells and healing springs in and around the ancient city of Edinburgh, Scotland. Written in a simple A-Z gazetteer style, nearly 70 individual sites are described, each with their grid-reference location, history, folklore and medicinal properties where known. Although a number them have long since fallen prey to the expanse of Industrialism, many sites can still be visited by the modern historian, pilgrim, christian, pagan or tourist.