Chambered Cairn: OS Grid Reference – NM 9227 3636

Also known as:

- Achnacridhe

- Canmore ID 23223

- Carn Ban

- Moss of Achnacree

- Ossian’s Cairn

Archaeology & History

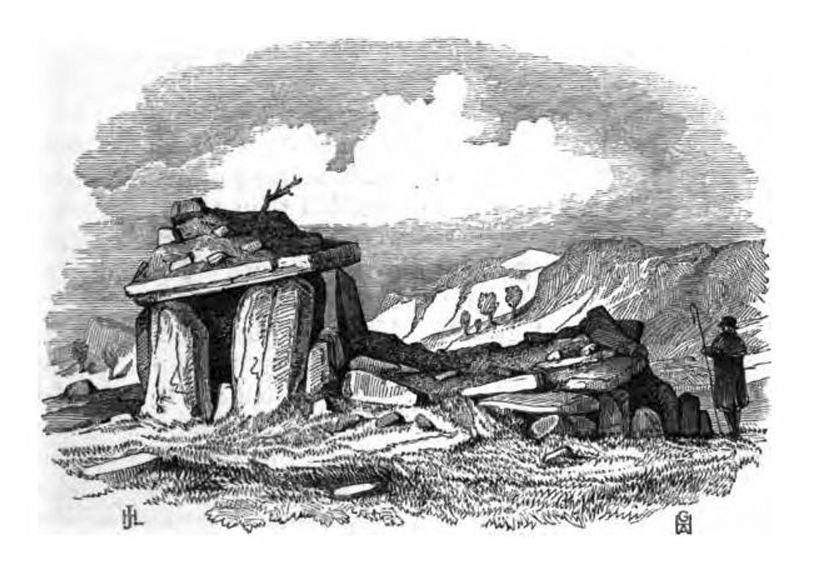

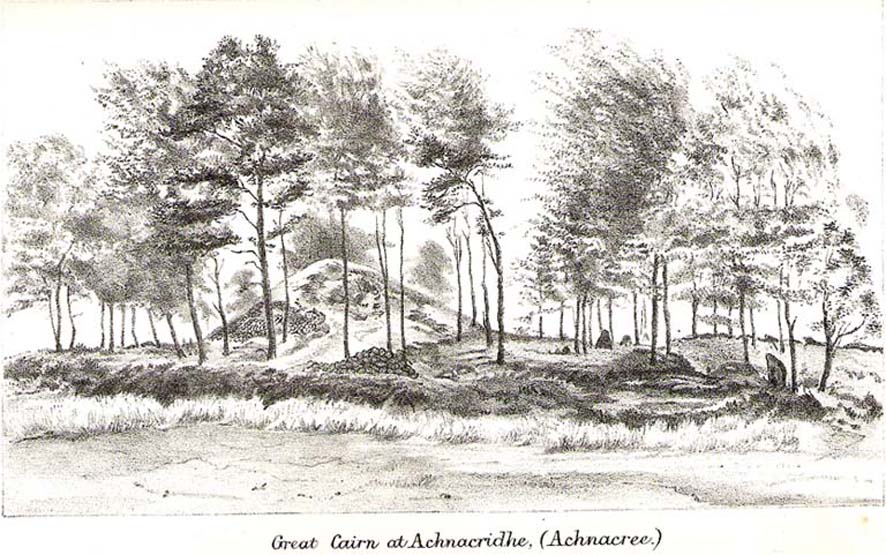

Not to be confused with the Achnacreebeag chambered tomb a short distance to the east, Achnacree is a site that has been made ruinous over the last 100 years, prior to which — as R.A. Smith’s (1885) illustration here shows — we had a quite grand prehistoric chambered cairn to behold. It’s still worth looking at though!

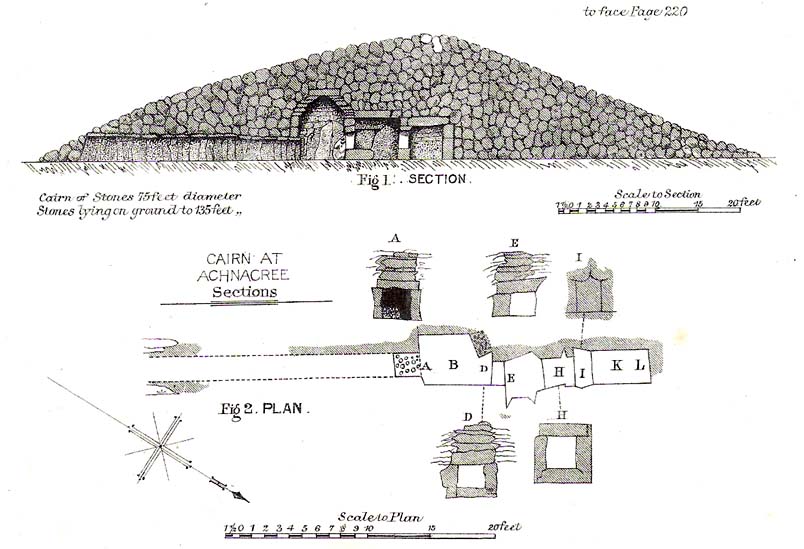

The once giant tomb is neolithic in age and nature, and was defined by Audrey Henshall (1972) as a passage grave of the Clyde Cairns group. It appears to have been built over two different periods: the earliest being when the first two internal chambers were done, “which in building technique and plan are comparable to a two-compartment Clyde-chamber and which may have been covered by a small cairn.” (RCAHMS 1974) Much later, the long passage seems to have been added and built over the original chambers.

Although Smith (1885) and Henshall describe the large cairn, the Scottish Royal Commission (1974) entry gives the most succint archaeocentric summary of the site:

“The cairn is about 24.4m in diameter and now stands to a height of some 3.4m on the S and 4.1m on the NE, although it is said to have been about 4.6m high before excavation; it consists of small and medium-sized stones, interspersed with a few large boulders. A low platform of cairn material, now grass-covered and about 1m high, extends round the base of the cairn and increases the overall diameter to about 40m. The entrance to the passage is on the SE side of the cairn and is marked by four upright stones, one of which is now leaning out of position. The central pair, set about 1.2m apart and protruding 1.3m and 0.4m above the cairn material, are the portal stones on either side of the passage, while the flanking pair may be the remains of a shallow forecourt. The passage, which measured 6.4m in length and 0.6m in width, was constructed of upright slate slabs about 1m in height, and the roof was composed of similar slabs. The excavator recorded that the passage was filled with stones, and these seem to indicate a deliberate blocking after the final burial-deposit. The chamber comprised three compartments. The outer, measuring 1.8m by 1.2m and about 2.1m in height, was constructed of upright slabs and drystone walling supplemented by corbelling, and was covered by a single capstone. The central compartment, measuring 2m by 0.7m and 1.6m in height, was entered across a large transverse slab, and the entrance itself appeared to have been deliberately sealed with stones ‘built firmly in after the chamber had been completed.’ The sides of this chamber were formed of blocks of stone supplemented by dry-stone walling, and it was roofed by a singular capstone. The inner compartment was entered across a sill-stone, and measured 1.4m by 0.9m and 1.7m in height. A combination of slabs and dry-stone walling had been employed in its construction, and it was roofed by a single massive capstone some 0.4m thick. Each side-wall was constructed of two slabs set lengthwise one above the other, in such a way that a narrow ledge was formed at their junction. On these two ledges a number of white quartz pebbles had been deliberately deposited… Three neolithic pottery bowls were discovered in the course of the excavation — a fragmentary vessel from the outer compartment, and one complete and one fragmentary bowl from the inner compartment.”

These bowls were sent to Edinburgh’s National Museum of Antiquities soon after being found.

Folklore

Those of you into earthlights will like this one! Also known as Carn Ban, or the White Cairn, aswell as Ossian’s Cairn, R. Angus Smith (1885:217) told how,

“it was curious…to listen to the superstitions that came out (about this tomb). One woman who lived here, and might therefore be considered an authority, said that she used to see lights upon it in dark nights.”

Another old local was truly terrified of the place, and said he would not enter this tomb for all the money in Lochnell Estate.

Regarding the various names given to the site, when Mr Smith (1885) wrote about it all those years ago, he told:

“We have often inquired the name of the cairn. The cairn really has had no definite name. Some people have called it Carn Ban or White Cairn, but that is evidently confusing it with the other cairn which we saw over the moss, and which is really whiter. Some people have called it Ossian’s Cairn, but that is not an old name, and even if it had been, we know that it is a common thing to attach this name to anything old. We call it Achnacree Cairn, from the name of the farm on which it stands.”

References:

- Henshall, A.S., The Chambered Tombs of Scotland – volume 2, Edinburgh University Press 1972.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – Volume 2: Lorn, HMSO: Edinburgh 1974.

- Smith, R. Angus,”Descriptive List of Antiquities near Loch Etive,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 9, 1870-72.

- Smith, R. Angus, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisneach, Alexander Gardner: London 1885 (2nd edition).

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian