Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 72780 16532

From Comrie take the B827 road to Braco, passing the large Roman Stone monolith, turning right at the tiny Glen Artney road a half-mile along (easy to miss). 3 miles on, pass the derelict Dalness cottage, you can follow the directions to get to the Mailer Fuar (2) cup-and-ring stone; and from here go up the field past the Mailer Fuar (1) carving, through the gate and follow the fence to your right, then drop down into the great boggy reeds, over the burn and up as if you’re heading to the rounded hill of Cnoc Brannan. On a grassy knoll a hundred yards or so up the slope, you’ll see a rock or two. It’s thereby!

Archaeology & History

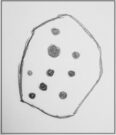

I came across this petroglyph not too long ago on the same day I found the Cnoc Brannan standing stone a little further up the slope from here. Covered in cup-markings over all except the northeastern portion of its surface, a faint ring seems to be around one of them on its northern side. Of the twenty-two cups on the stone, the majority of them, as the photos show, are clustered alongside a curved natural scar that runs across the topmost section of the rock. There are less pronounced faded cups on the more northern and western portions of the rock, with what looks like one on its near-vertical southern face. Despite its lack of complexity, it has an impressive feel to it.

The home of this carving in its natural setting is what stands out when you’re up here and is certainly what gives it that vibe! The wooded greenery of Glen Artney stretches ahead of you to the east and west, with the craggish mountains of Beinn Dearg, Halton and their compatriots drawing you to the northern side. Tis a gorgeous arena indeed! So, if you’re going to visit its near neighbors at Mailer Fuar a half-mile below, stick this one on your itinerary and, if you’re the roving type, get your feet wet and look around for some more of them. There’ll be others, as yet unknown, hiding away nearby…

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian