Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 88161 24176

From Gilmerton village, take the A822 Dunkeld road north. Go for about 200 yards and take the little road to Monzie; watching carefully another 200 yards on for the dirt-track on the left taking you across the fields. Go along the track, watching out for the small stones in the field on your right less than 200 yards along. You can’t really miss ’em! This small ring of stones is the Monzie Cairn Circle. The carving is just in front of it!

Archaeology & History

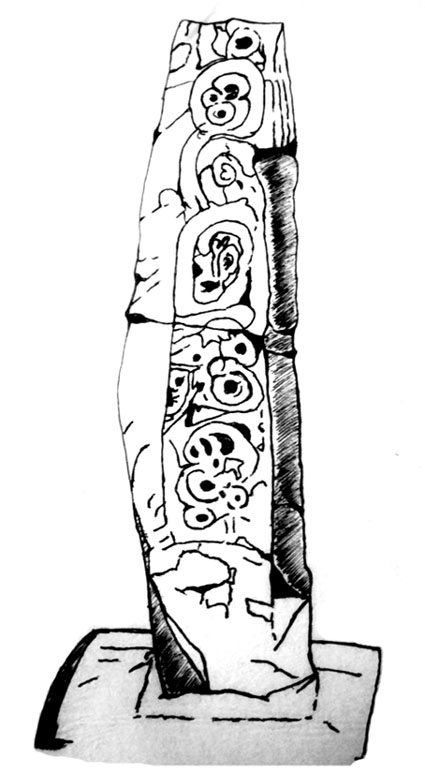

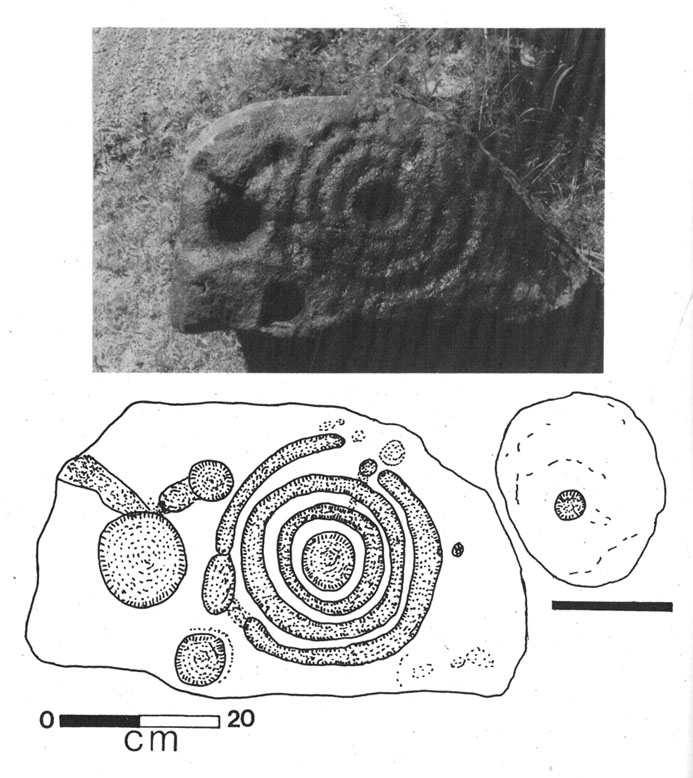

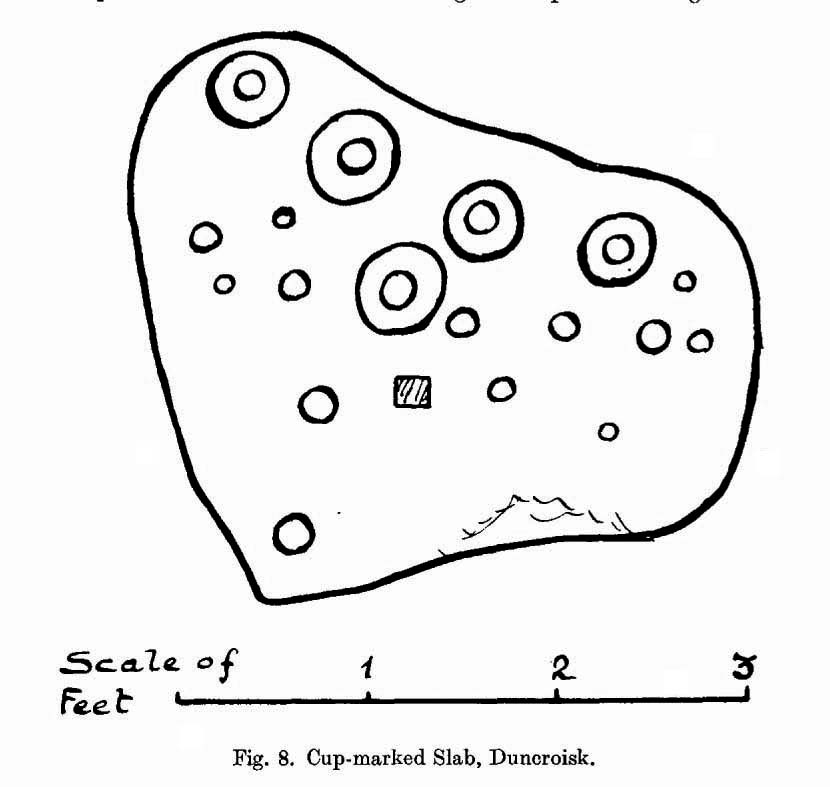

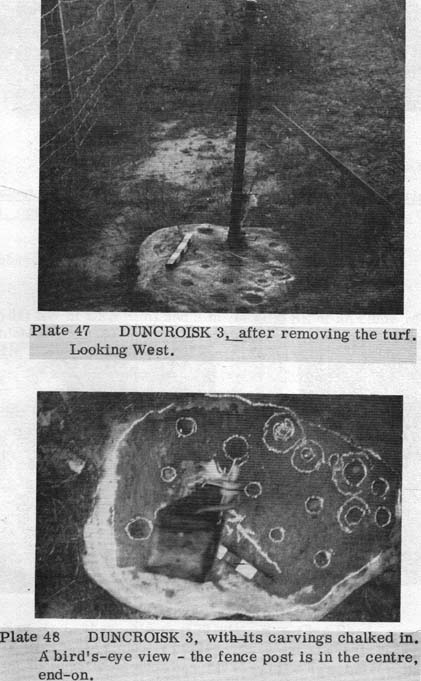

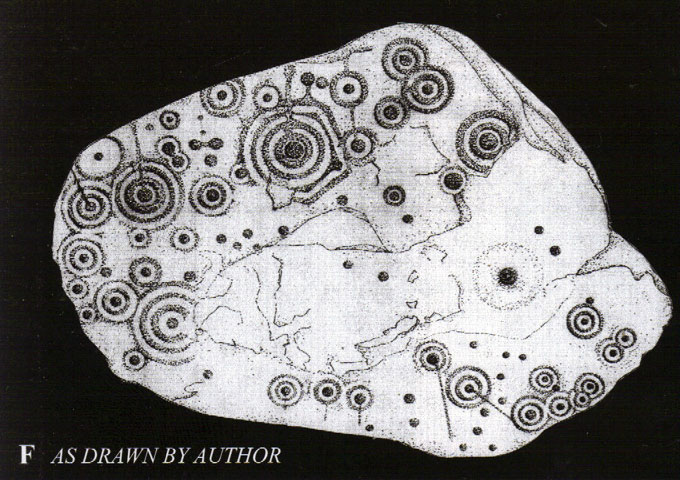

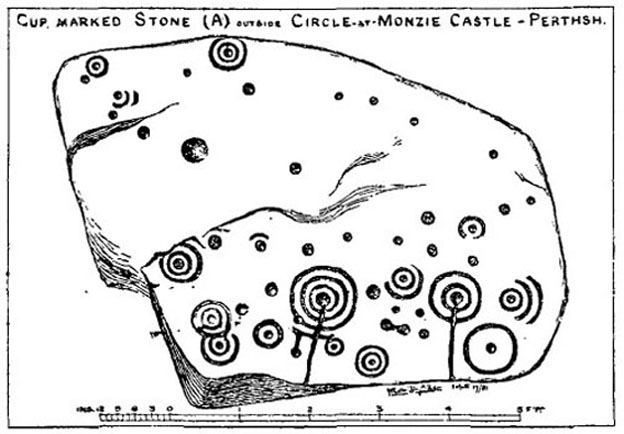

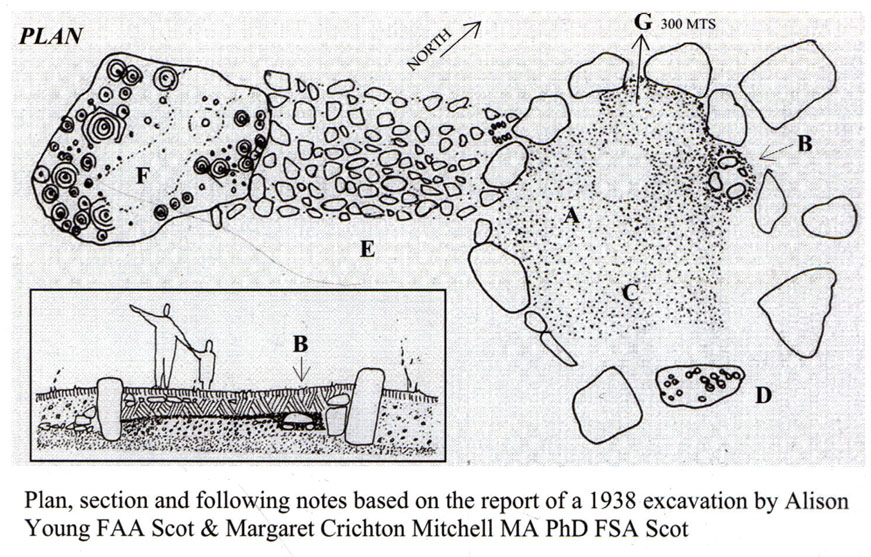

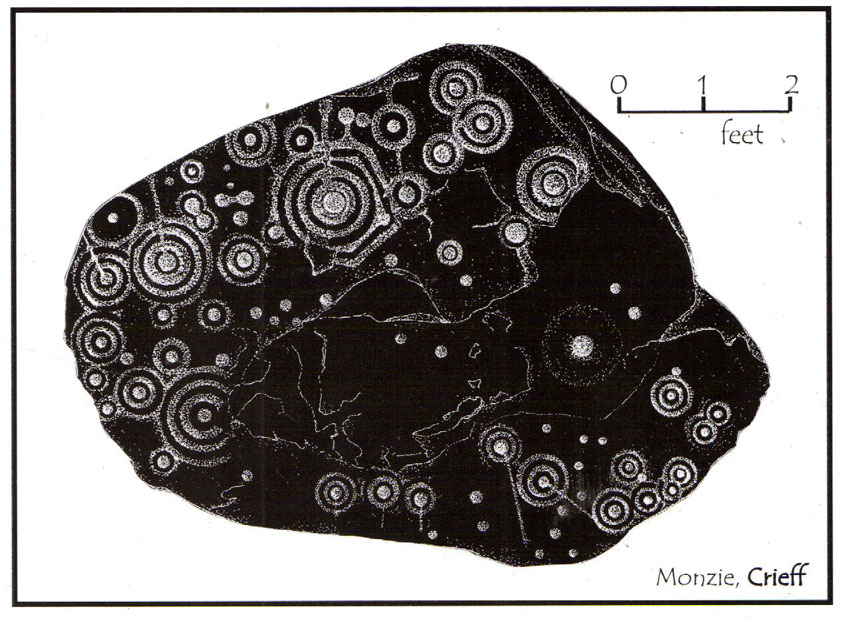

Although we know this brilliant carved stone has some relationship with the Monzie cairn circle only five yards away (it was linked via a man-made stone causeway, running between the circle and the carving), the stone itself is very much deserving of its own entry here — and at the same time I can give Andrew Finlayson’s (2010) excellent book a decent plug aswell! (the superb drawings of the stone, top & bottom, are from Andy’s work)

First mentioned (I think) in Simpson’s (1867) early survey, the carving was described soon after by J. Romilly Allen (1882), who gave us an early drawing of the stone. Thought by some to have originally stood upright, the carving was described by Aubrey Burl (2000) as being, “decorated with forty-six cupmarks, cup-and-rings, nine double, one triple, there are grooves and a pair of joined cups.” It’s certainly an impressive carving!

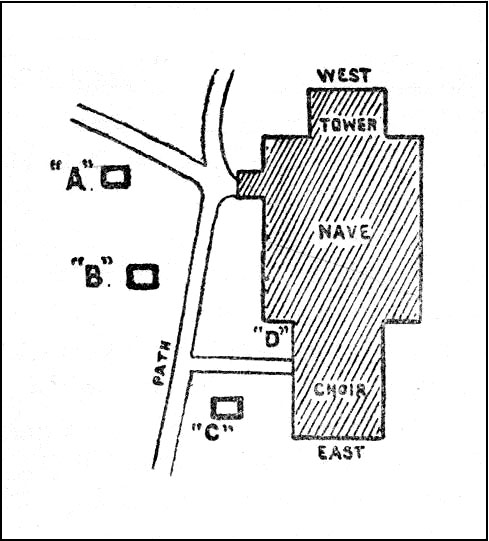

Although the carving has been posited by some archaeologists as an outlier to the Monzie circle, it’s probable that the circle emerged from the carving — a concept that some may find difficult to understand. I’m not aware of any modern excavations here (the last, I think, was in 1938), but my guess would be that the stone causeway laid between the cup-and-ring stone and the circle ran towards the circle from the carving, and not the other way round. The carving is probably older than the stone ring — though of course, without excavation, my idea could be utter bullshit! (there are also some cup-marked stones in the circle aswell – though none as impressive as this)

One of my truly favourite megalith fanatics (despite some of his alignments being out), Alexander Thom, came here and thought this old carving “coincided with a rough stellar alignment from the centre-point of the cairn” (Hadingham 1974); though his notes in Megalithic Rings (1980) tell that,

“from the cupmarked stone beside the circle, the midsummer sun sets above an outlier some 800ft distant.”

The “outlier” that Thom mentions is known as the Witches’ Stone of Monzie; which Simpson (1867) appears to have mistakenly thought was the name of this very carving.

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “Notes on some Undescribed Stones with Cup Markings in Scotland,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 16, 1882.

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Finlayson, Andrew, The Stones of Strathearn, One Tree Island: Comrie 2010.

- Hadingham, Evan, Ancient Carvings in Britain, Garnstone: London 1974.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

- Thom, Alexander, “Megalithic Astronomy: Indications in Standing Stones,” in Vistas in Astronomy, volume 7, 1966.

- Thom, A., Thom, A.S. & Burl, H.A.W., Megalithic Rings, BAR: Oxford 1980.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian