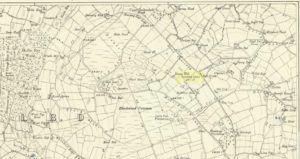

Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SE 04436 18247

Also known as:

- Ring of Stones

- Wolf Fold

- Wolf Stones

From Ripponden, taken the steep road up to Barkisland, but at the crossroads just before the village, turn right (south) and keep going for a mile till you reach the reservoir. At the far-end of the reservoir, take the track down by its side and follow the footpath that bends round the edge of the grasslands. Go up onto this small moorland and, once you’re on the level, head towards where you’ll see a large pile of stones a coupla hundred yards away. That’s it!

Archaeology & History

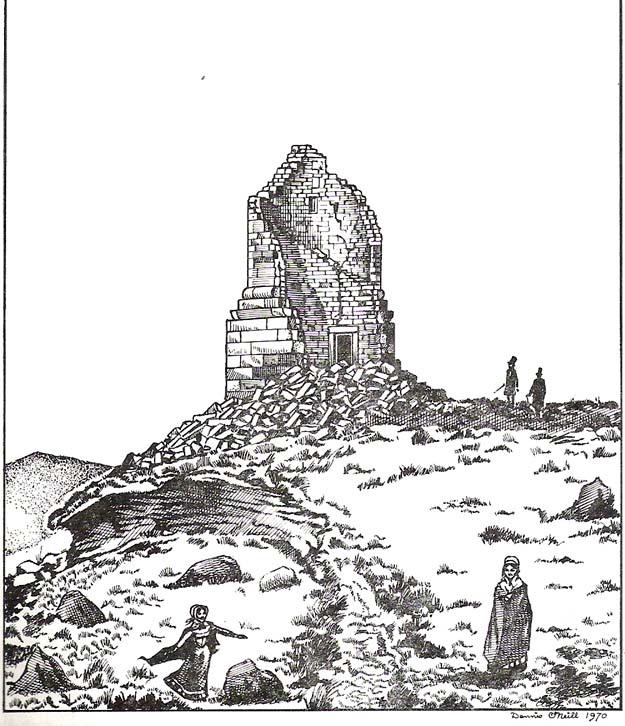

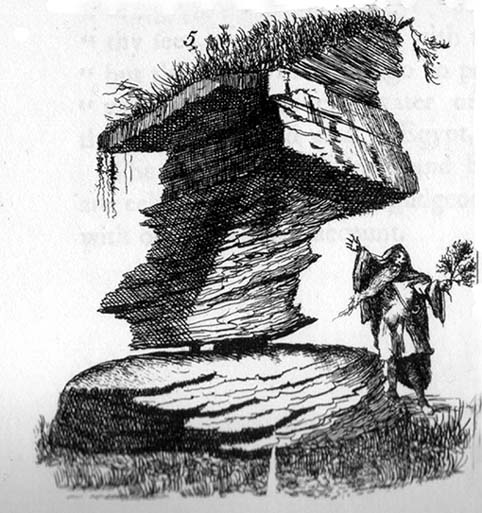

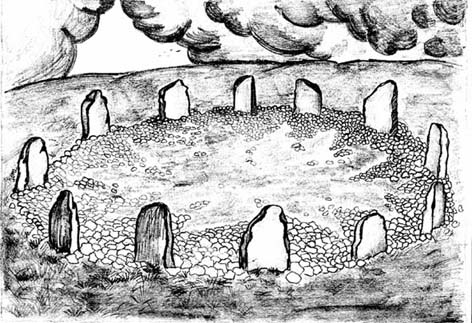

If we visit this site today, all we are left with is a scattered mass (or perhaps that should that be ‘mess’) of many hundreds of stones: the last remnants of what once would have been a proud circle of one form or another upon this small moorland plain. Its significance was such that the very moor on which its remains are scattered, was named after it: the Ringstone Edge Moor. But as with many sites from our megalithic period, this old place is but a shadow of its former self.

Gone are the upright monoliths which, tradition relates, once surrounded this low scattered circle of small loose stones (which would have made it look not unlike the wonderful stone circle of Temple Wood, Argyll). These standing stones were, so the folk record tells, removed near the end of the 18th century for use in some walling.

Described variously as a stone circle, ring cairn, cairn circle, an enclosure, and more, the site first seems to have been written about in 1775 by the great historian John Watson. When he was vicar of the local parish in Halifax (not far from here) this “ring of stones” as he called them, was “called the Wolf-fold.” Nearly one hundred years later, in F.A. Leyland’s superb commentary to Watson’s work, he wrote,

“The stones which constituted the circle at the time of their removal stood upwards of three feet…and the remain formed a striking object on the moor. The original number of stones of which the circle was formed is unknown, having long been in ruin and reduced in quantity before being finally removed. This was effected about twelve years since by the present tenant of the dam.” – that is, around 1859.

However, when Crabtree (1836) described the circle a decade or two earlier, he made no mention of such standing stones — although we must consider that Crabtree was very much like many modern academic archaeologists who tended to copy the works of others, much less than getting out in the field to see for himself.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the lore telling of the standing stones’ demise was repeated by local historian John Priestley (1903), when he said that: “all the large stones…were carted away about forty years ago” — that is, around 1863.

So it would seem that the very final destruction of the standing stones here, occurred sometime during the four year gap which Messrs. Leyland and Priestley describe.

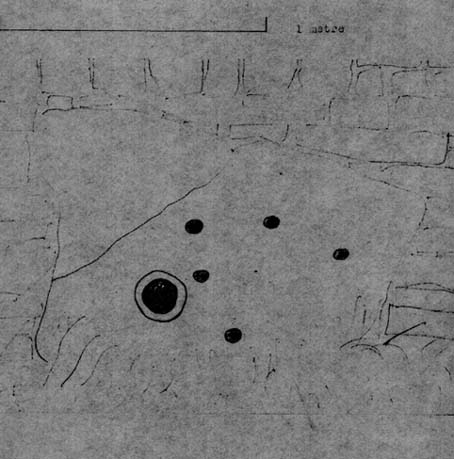

More than fifty years later, Huddersfield historian James Petch (1924) came here to explore whatever remains he could find, and told:

“On top of a flat plateau on this moor, with an extensive view on all sides save on the north, where there is a gentle slope for some hundreds of yards up to the summit of the hill, there are distinct traces of a circular ring of small stones. Pygmie flints have been picked up within a yard or two, but the only other fact to be noted about this earthwork is that there is a tradition to the effect that much earth has been removed from this site. It is not altogether impossible that this is a scanty remnant of a round barrow.”

This latter remark of Mr Petch seems most probable. The excessive scatter of small stones typifies the remains of many of the Pennine giant cairns, from the Little Skirtful on Burley Moor and giant tombs of the Black Hills near Skipton, to the similar monuments of our Devil’s Apronful, Pendle, etc, etc.

Close to this cairn circle, wrote Sidney Jackson (1968), there used to be the remains of an Iron Age settlement, “marked by wall foundations (but) is now covered by the waters of Ringstone Reservoir.”

Folklore

There is very little folklore that I’ve found here. Watson (1775) throws the usual idea that the place was a site of druidical worship; but other than that we only have a local Ripponden writer’s account, which told that there was once the ghost of a white lady that was once said to walk along the path somewhere between here and the Beacon Hill tumulus, a short distance to the north.

…to be continued…

References:

- Abraham, John Harris, Hidden Prehistory around the North West, Kindle 2012.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Crabtree, John, Concise History of the Parish and Vicarage of Halifax, Hartley & Walker: Halifax 1836.

- Jackson, Sidney, “Tricephalic Heads from Greetland, Yorks,” in Antiquity journal, volume 42, no.168, December 1968.

- Keighley, J.J., ‘The Prehistoric Period,’ in Faull & Moorhouse’s West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Guide to AD 1500, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Leyland, F.A. (ed.), The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax by the Rev. John Watson, M.A., R. Leyland: Halifax n.d. (c.1867)

- Longbotham, A.T., ‘Prehistoric Remains at Barkisland,’ in Proceedings of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, 1932.

- Petch, James A., Early Man in the District of Huddersfield, Advertiser Press: Huddersfield 1924.

- Priestley, John H., The History of Ripponden, John Mellor: Ripponden 1903.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 3, Cambridge University Press 1963.

- Watson, Geoffrey G., Early Man in the Halifax District, HAS: Halifax 1952.

- Watson, John, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax, T.Lowndes: London 1775.

- Whiteley, Hazel, Ryburn Tapestry, Halifax Evening Courier n.d. (c.1974)

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian