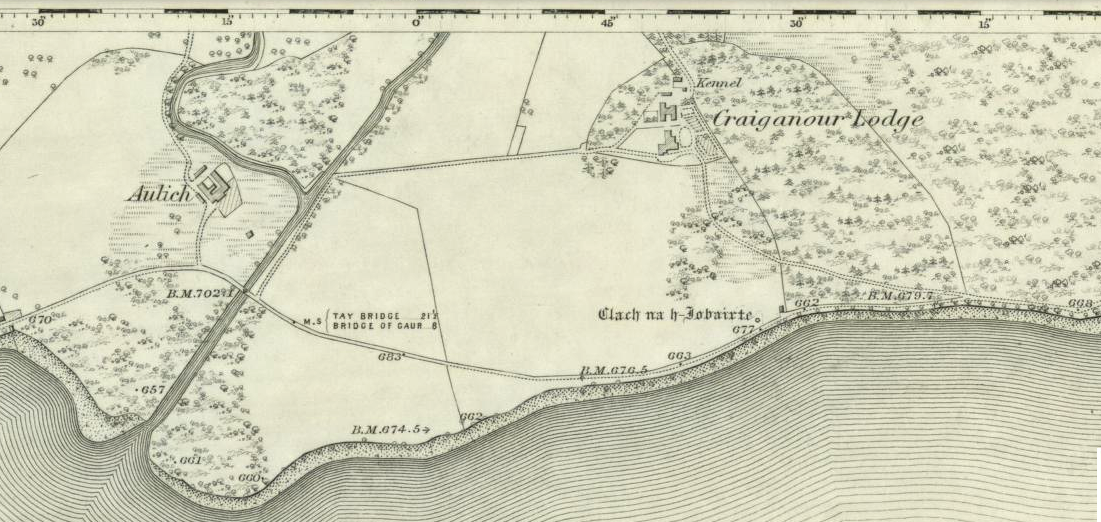

Enclosure: OS Grid Reference – NN 86680 00601

This really take a lot of effort to find. From Alva, go up through the graveyard past St. Serf’s Well, turning left and across cross the lane. A gate into the field takes you past Rhodders Farm then up the zigzagging track up the steep hill called The Nebit and into the Ochils. Where the track stops zigzagging, keep your eyes peeled for a left turn (west) about 1000ft up. Go along this, parallel above Alva Glen, for about 2 miles till you reach the sheep fanks. Naathen – go straight uphill towards Bengengie peak, steering to the right (north) side, avoiding the cliffs and onto the level moorland. Once there, you’ll see a rounded hillock a coupla hundred yards ahead. That’s the spot!

Archaeology & History

This is a bittova long hike to see a very overgrown site – but if you really enjoy the hills, it’s a good little side-track to visit. I came across it recently on a long bimble over the Ochils, on my way back home after travelling to three of the Ochil peaks. Walking carefully across the swampy heights of the Menstrie Moss, a rounded hillock north of Bengengie seemed to have the pimple of a cairn on its top—so I veered over to have a look.

The cairn was small and overgrown, with just a half-dozen rocks visible above ground, and a collection of others in the same pile beneath the heathland grasses. It was obviously a man-made assemblage, but I couldn’t say for sure whether this was the grave of a person or someone’s favourite sheep a few centuries back!

It was when I walked around the cairn to try and get some photos of it, that another very distinct feature—not immediately visible—stood out and gave this single cairn a series of additional ingredients that really brought this site to life! For just a few yards east of the cairn I noticed an obvious ditch and outer embankment, running roughly north-south, which may have relevance to the pile of stones. And so I walked along the edge of the embankment, for about 10 yards, only to find that it turned to the right and continued onwards, east-west, for some distance. This then turned at a similar angle again about 30-35 yards along, and then again, and again, until I returned to where I had stood initially a few minutes earlier!

There was no doubt about it: this was a man-made, roughly rectangular-shaped enclosure, whose bank and ditch averaged 1-2 yards across. The maximum height of the outer embankment is less than 3 feet. Its eastern and western lengths measured roughly 17-18 yards long, and the longer lengths north and south were between 30 and 35 yards at the most. The cairn feature that I’d initially noticed is found at the near-eastern edge of the enclosure. Apart from that, my initial ramble here indicated few other internal features that were visible, except several small stones.

The great majority of the site is very overgrown and, as you can see, the photos of the ditch and bank constituting the enclosure are sadly not that easy to make out. You can see it mostly by the colour changes of the vegetation, running in lines either across or up through the middle of the photos. I need to get up there again and try get some better images sometime soon—and also to see if there are other features hiding away on the heights of these old hills, long since said to have been the abode of one of the great Pictish tribes (there is also a considerable mass of old faerie-lore in these hills, indicating considerable ancient activity of people whose cosmos was inhabited by spirits and forms long since forgotten in the consensus trance of most moderns).

As for the age of the enclosure: it’s difficult to say on first impression and I’m not keen on making a guess on this one. It’s certainly old, as the overgrown vegetation clearly shows, both on the photos and when you see it first-hand. It’s already been suggested by one graduate as possibly neolithic, but I’m a little sceptical about that, as its linearity isn’t consistent with neolithic features we know about in the mid-Pennines. However, this geographical arena is new landscape for me and so the possibility remains open until better, more competent investigation gives us a clearer time period.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian