Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NT 22741 86948

Also Known as:

- Binn House

- Canmore ID 269301

- Craigkelly

- Silverbarton Farm

From Burntisland, go up the Cowdenbeath road for just over half-a-mile, then turn right and walk into the woods up the footpath. Go uphill, over the first stile until you reach the field less than 200 yards above. Follow the line of the trees, right, along the edge of the field for about 100 yards, then walk uphill into the trees again until you reach a small rocky outcrop. That’s the spot!

Archaeology & History

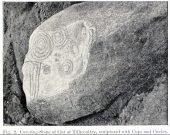

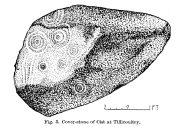

Rediscovered in the summer of 2003, this is one in a small cluster of little-known petroglyphs on the western slopes of the hill known as The Binn. Found less than a yard away from another carving, this ornate-looking fella consists of a wide cup-mark with three very well-defined concentric rings around it. A carved line runs out from the central cup, down the gentle slope of the rock and out of the rings entirely; whilst 60° left of this line, a second one runs from the central cup to the inner edge of the third concentric ring. To the left of the 3-rings is another concentric system, with one clear ring around a faint shallow inner-cup and what seems to be a faint outer secondary ring. A possible third isolated cup-mark is to the top-left of the multiple rings.

This is one of two carvings that are right next to each other and it is curious inasmuch as the erosion on it seems negligible. This may be due to the overhanging rock which shelters it considerably from normal weathering processes. Indeed, if the carving was uncovered from beneath a covering layer soil, the lack of erosion on it makes complete sense. However, I have to say that I was slightly skeptical about assigning any great age to this particular design—and until we get an assessment from a reputable geologist we should perhaps be cautious about giving it a definite prehistoric provenance. It’s still very much worth seeing though. The carving on the adjacent rock however, is a different kettle o’ fish altogether!

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Penny Sinclair for guiding us to this little-known site. Cheers Pen.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.