Stone Circle: OS Grid Reference – NN 76785 42490

Also Known as:

- Acharn Falls

- Auchlaicha

- Canmore ID 25004

- Queen’s Wood

- Remony

From Kenmore, take the minor road on the south-side of Loch Tay for 1½ miles (2.4km) until you reach the hamlet of Acharn. From here take the track uphill for ½-mile past the Acharn waterfalls and follow the same route to the Acharn Burn tumulus. Walk past here along the track and, just before you reach the wooded burn, bear right and walk uphill for nearly another half-mile, roughly parallel to the Allt Mhucaidh (Remony Burn). As you reach the proper moorland, you’ll see the stones rising up!

Archaeology & History

This is quite a spectacular site! Not for the size of the stones or the arrangement of the megaliths, but for the setting! It’s outstanding! When a bunch of us wandered up here a few months ago, snow was still on the peaks and Nature was giving us a real mix of Her colours and breath in a very changeable part of Her season. Twas gorgeous. Perhaps the setting was the thing which has kept the circle pretty quiet until recent years. It’s high up – and out of season the freezing winds and driving rains would keep all but the healthiest of crazy-folk away. We all only wished we’d have had more time here. But that aside…

Along with the changeable weather She gives up here, the literary-types have given this circle changeable names too. Nowadays known as the Acharn Falls stone circle, in truth that’s a mile away and lacks in both visual and geographical accuracy. ‘Greenland’ was the name cited when J.B. MacKenzie (1909) wrote about it more than a hundred years back, and it’s the name we find in Mr Burl’s (2000) magnum opus, despite him telling how “a local name for it is Auchliacha, ‘the field of stones'” (Burl 1995), so perhaps we should adhere to what the locals say (my preference generally).

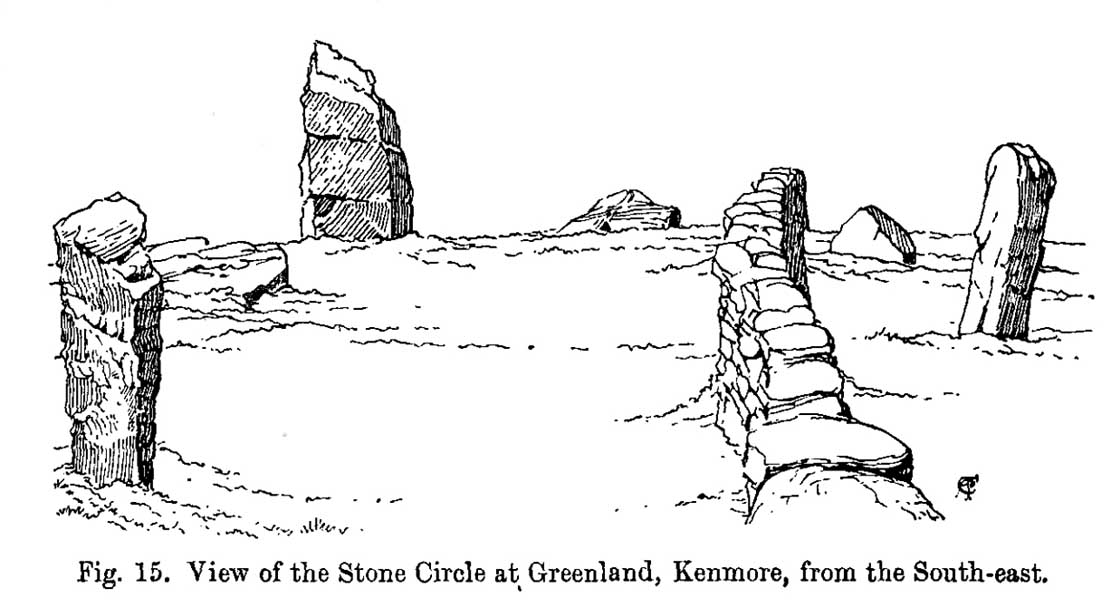

The ring is in quite a mess, having had a drystone wall built through it in the last 100 years. No walling is shown on the early Ordnance Survey maps, so some local land-owners (an english incomer?) was probably responsible. The stones used to stand in parts of the ancient forest, which must have looked and felt quite something before they ripped the trees away. It was hiding away in the woods when J.B. MacKenzie (1909) came here, shortly after the “modern wall” as he called it, had been constructed through the circle. He wrote:

“Six stones remain on the site, of which four are still erect and in position, and two are prostrate, one of which has apparently fallen inwards and the other outwards of the line of the circle, the diameter of which, touching the inner sides of the stones still standing, is 27 feet 9 inches. Mr MacLeod has supplied the following dimensions of the several stones:

A — 6 feet 9 inches x 3 feet 6 inches, lying flat

B — 8 feet 4 inches, in circumference at ground level

——1 foot 7 inches, high above the ground level

C — 6 feet 10 inches, in circumference at ground level

——4 feet 0 inches, high above ground level

D — 6 feet 0 inches, in circumference at ground level

——4 feet 3 inches, high above ground level

E — 7 feet 8 inches x 4 feet 6 inches, lying flat

F — 9 feet 0 inches, in circumference at ground level

——5 feet 8 inches, high above ground level.”

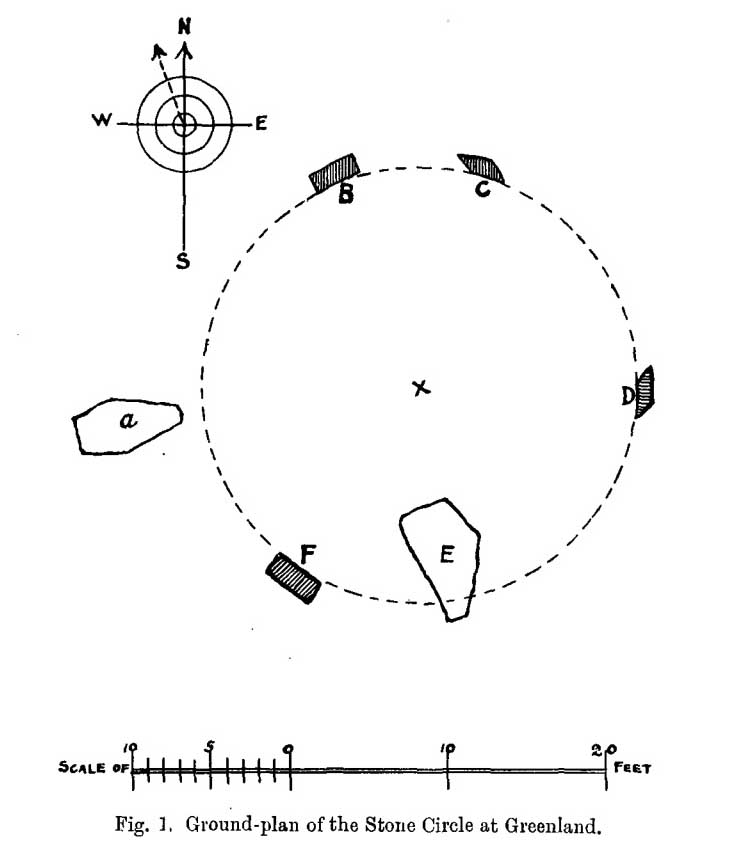

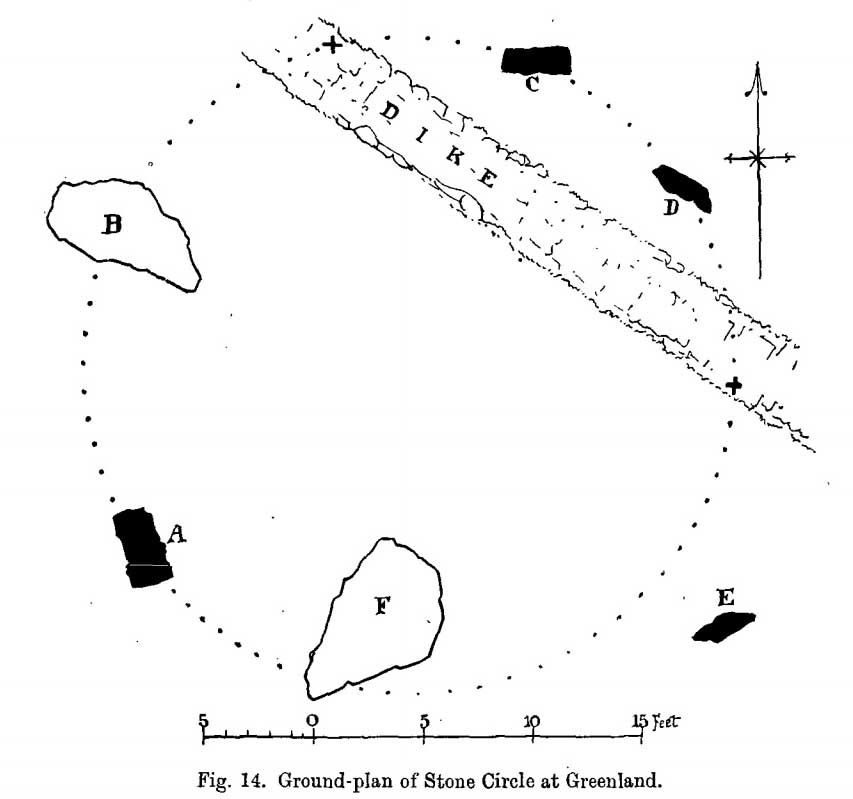

The year after MacKenzie’s notes, the great Fred Coles (1910) paid a visit here. Noting how high it was in the landscape compared to other megalithic rings in the region (it’s the highest known circle, at 1240 feet up), he went on to give his usual detailed appraisal, telling:

“In a little clearing amid these woods on Craggan Odhar, but disfigured by a dike which separates some of the Stones from the others, stands this Greenland Circle of which the ground-plan is given…. The Stones are six in number, of which four are erect, and they all appear to be of the quartzitic schist. Some disturbance has occurred, and it seems probable that there were at least two more Stones originally, one between B and C at the spot marked with a cross, and the other similarly marked midway between D and E. There is, however, no vestige of any Standing Stone in the sides of the dike itself.

“On the south-west is Stone A, the tallest, with pointed top, 5 feet 7 inches in height, oblong in contour, and measuring at the base 9 feet 5 inches. Having several deep horizontal fissures, this Stone…bears an odd resemblance to masonry. The next Stone, B, lies prostrate, measuring 7 feet 9 inches by 4 feet, and about 1 foot in thickness above ground. The little oblong Stone, C, on the other side of the dike, stands only 1 foot 10 inches above ground, and probably is a mere fragment—the stump of a much larger block. At D the Stone is 4 feet 3 inches in height, and is a very narrow slab-like piece; Stone E, which has a decided lean over towards the interior of the Circle, is 4 feet 2 inches high, and is in basal girth 6 feet 6 inches. Like the others, it is angular and thinnish in proportion to its breadth. Stone F measures 8 feet 2 inches by 5 feet 2 inches, and its position, with the narrow end resting almost on the circumference, suggests, as in other cases, the probability that it was this narrow end which was buried when the Stone was erected. These blocks were most likely brought from the low cliffy ledges near, for, as the name ‘Craggan Odhar’ implies, the place was, before being planted, conspicuous for its Grey Crags.”

Although no modern excavation has taken place, when the brilliant local historian William Gillies (1925) first got round to exploring the circle, he remedied that situation. In probing the ground beneath the surface when the weather conditions allowed, Mr Gillies found that there seemed to have been more standing stones in the circle than presently meets the eye. He wrote:

“I paid several visits last summer to this lonely and elevated spot, and examined the ground for stones, where the wide spaces between those indicated on the plan (see Coles’ 1910 drawing, above) suggested that others might be concealed beneath the turf. There would appear to be three stones missing, which would make the circle to consist of nine in all when it was entire. With little trouble, at a depth of only 3 inches, I located a large flat stone measuring 5 feet 6 inches by 4 feet 8 inches. It had stood on the north-western arc of the circle half-way between the fallen stone on the west and the broken standing stone on the north-north-west. It had fallen outwards. The foundation of the wall, built probably some seventy years ago to enclose the plantation, rested on the edge of the stone. The ground along the circumference of the circle between the three stones on the eastern side was carefully probed, but the rod touched only small loose stones.

“I next turned up the centre of the circle, and at a depth of 5 inches below the surface came upon a dark deposit. It extended over a space of 2 feet square and was about 5 inches in depth. It was mixed with a white limy substance consisting of calcined bones, bits of which along with a sample of the dark substance I brought to the Museum. A bit of charcoal from the deposit revealed the lines of cleavage in the wood. There is no peat at the spot, although the elevation, which is at least 1200 feet, might suggest it. The surrounding soil is of a reddish colour, and quite unlike the deposit which must have been placed there, and which was probably a burial after cremation.”

Gillies was exemplary in his exploration of sites that were on the verge of disappearing from tongue and text and we remain incredibly grateful for his later exposition on the antiquarian remains and legends of this truly stunning landscape. In Aubrey Burl’s (1995; 2000) respective summaries of this stone circle, as well as that of John Barnatt (1989), they ascribe the situation of it originally having 9 stones, as Gillies suggested.

Visit this site! If you’re into megaliths, you’ll bloody love it!

References:

- Barnatt, John, Stone Circles of Britain – volume 2, BAR: Oxford 1989.

- Burl, Aubrey, A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 1995.

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Coles, Fred, “Report on Stone Circles Surveyed in Perthshire (Aberfeldy District),” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 44, 1910.

-

Gillies, William A., “Notes on Old Wells and a Stone Circle at Kenmore“, in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 59, 1925.

- Gillies, William A., In Famed Breadalbane, Munro Press: Perth 1938.

-

Mackenzie, J B., “Notes on a Stone Circle at Greenland, Parish of Kenmore“, in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 43, 1909.

- Money, Bob, Scottish Rambles – Corners of Perthshire, Perth 1990.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to the unholy bunch who helped travel, locate, photograph and take notes on the day of our visit here, including Aisha, Lara & Leo Domleo; Lisa & Fraser; Nina and Paul. Let’s do it again and check out the unrecorded stuff up there next time!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian