Enclosure / Settlement: OS Grid Reference – SE 0496 1747

Getting Here

If you’re coming via Ripponden, take the B6113 road uphill to Barkisland; but if from the Huddersfield direction, take the B6114 to Barkisland. Once in the village, stick to the B6114 Saddleworth road going south. After passing the unmissable Ringstone Edge reservoir (the Ringstone circle is on its far side) the Saddleworth road begins to straighten out and you hit the large quarry on your right. But before the quarry entrance, keep your eyes peeled on your left for the minor Scammonden Road that slopes downhill. 50 yards down, a gate and stile allows you into the field on your left (north) where you’ll see the scruff of earthworks. Y’ can’t really miss it

Archaeology & History

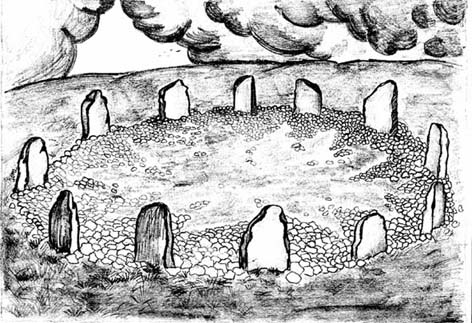

On the face of things, this is nowt much to look at unless you’re a prehistoric settlement freak! It is however a very notable rectangular set of ditches and embankments, with the ditches averaging between 10-12 feet across and 3-4 feet deep in places; whilst the raised banks vary between 13-20 feet across. The place was quarried into sometime at the end of the 19th century, casusing obvious damage, but its outer ramparts are still plain to see. It’s been known about for quite a few centuries too. Even before the Ordnance Survey lads had stuck it onto their brilliant mapping system, the great John Watson (1775) described these old ruins as,

“a piece of ground inclosed within deep ditches, on the side of the hill called Pikelow, one of which, to the west, is fifty-three yards long, full five yards wide, and about two yards deep; the opposite side to this cut by a wall and a road, but is very visible in the adjoining field, the plough not having yet been able to destroy it. The ditch to the south measures also fifty-three yards, but it is not so entire as the other. There is an opening at each corner of the western ditch which, if continued, would make the whole to be ninety-six (sic) yards each way. One of the sides towards the east is nearly levelled, the rest is in good preservation.”

He thought the remains to be Roman—a sentiment echoed by local archaeologist James Petch in 1924. More recently however, following a small excavation at the site by the Huddersfield Archaeology Group, Faull & Moorhouse (1981) suggested it to be Iron Age in nature—though with no hardcore evidence to confirm one way or the other. When Arthur Longbotham (1933) assessed Meg Dyke in his short rare work, the Roman question was explored—and ditched. Instead he thought that this settlement was “very likely the place of assemblage of all the warrior Brigantes from the surrounding hills and villages.” I think it’s likely that this is pretty close to the mark. My take on the place is a similar one, i.e., it’s either Iron Age or Romano-British in nature, simply due to its similarity with other remains from those periods: the Cowling’s enclosure on Askwith Moor being one such example.

References:

- Faull, M.L. & Moorhouse, S.A. (eds.), West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Guide to AD 1500 – volume 1, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Longbotham, Arthur T., Prehistoric Remains in Barkisland, Halifax 1933.

- Petch, James A., Early Man in the District of Huddersfield, Tolson Memorial Museum: Huddersfield 1924.

- Watson, John, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax, T. Lowndes: London 1775.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.