Standing Stones: OS Grid Reference – NO 04489 41057

Also Known as:

- Doo’s Nest

- Druid’s Stones

- New Tyle

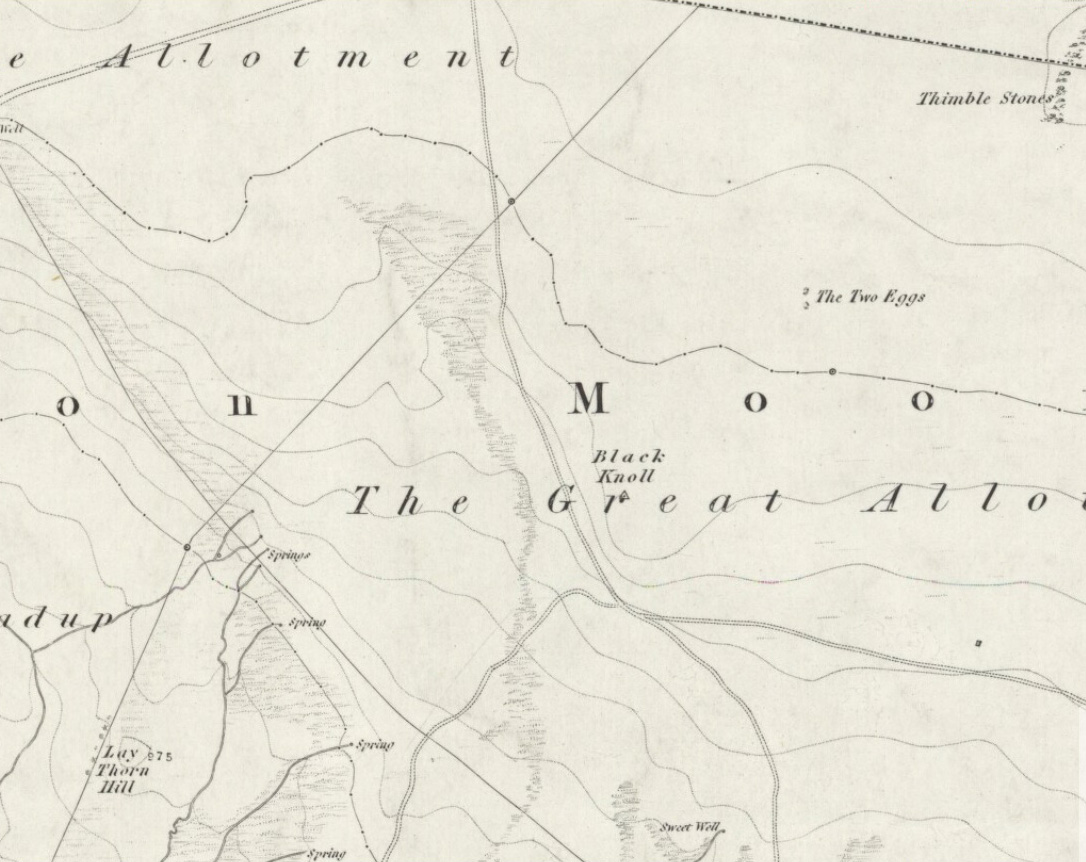

From Dunkeld travel southeast on the A984 road to Caputh and after about 1½ miles, set back a few yards from the road amidst the trees below the Newtyle Quarries (whose mass of slate and loose rocks cover the slopes), you’ll see these two large monoliths. There’s nowhere to park here, but there’s a small road a coupla hundred yards before the stones aswell as a space to park on the verge by the side of the road a few hundred yards after them. Take your pick!

Archaeology & History

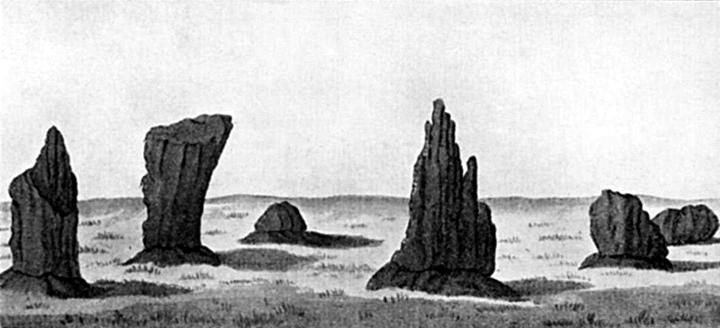

When we visited these two tall standing stones a few weeks ago, guerilla archaeologist Hornby and I were a little perplexed at the state of these stones, wondering whether they were a product of the fella’s who dug the quarries above here, or whether they were truly ancient. It seems the latter is the consensus opinion!

They were described by the great Fred Coles (1908) in one of his lengthy essays on the megaliths of Perthshire, where he thought the two stones here were all that remained of a stone circle that once stood on the flat, above the River Tay, but whose other stones “were destroyed in the making of the road” which runs right past here. Not so sure misself! He told that,

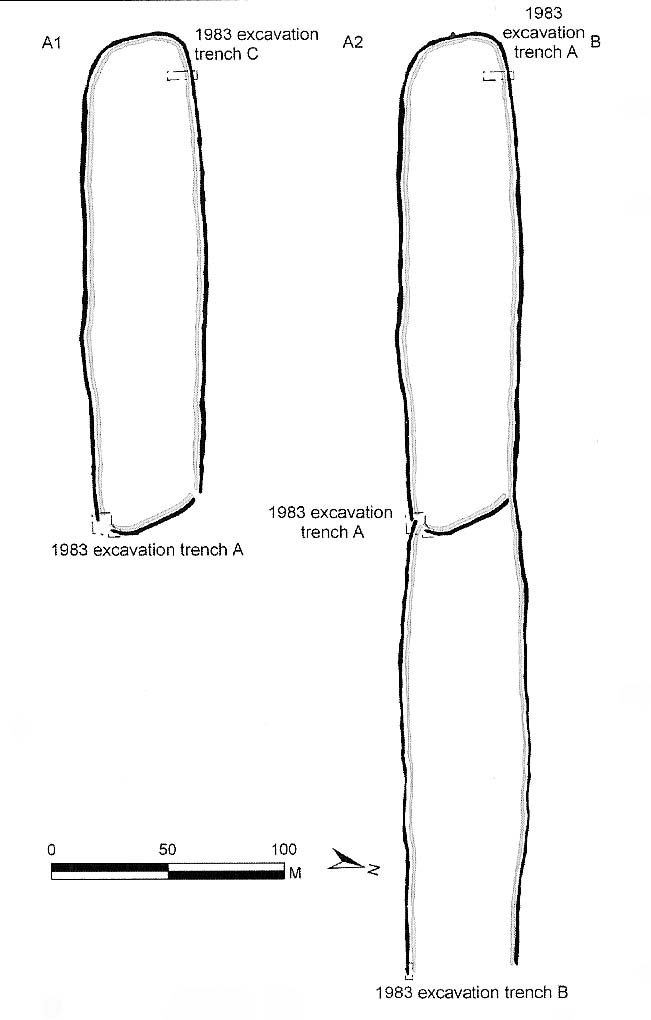

“An old cart-track runs up between the stones, leading from the main road…up to the quarry. The mean axis of the two stones runs N 13° W and S 13° E (true), and although their broader faces do not point towards the centre of a circle on the west, it is certainly much more probable that the other stones were on this side, the lower and flatter ground, than on the east, where the ground slopes and is more broken and rough.

“Both stones are of the common quartzose schist, but they differ considerably in shape. A is 6 feet 7 inches high at the north corner, but only 4 feet 10 inches at the south, and its vertical height at the east is only 3 feet. The basal girth is 13 feet 3 inches, and in the middle 15 feet 9 inches. The broad east face measures 5 feet. Stone B is level-topped and 5 feet in height; it has a basal girth of 12 feet 4 inches, and at the middle of 11 feet 8 inches. Its two broad faces are of the same breadth.”

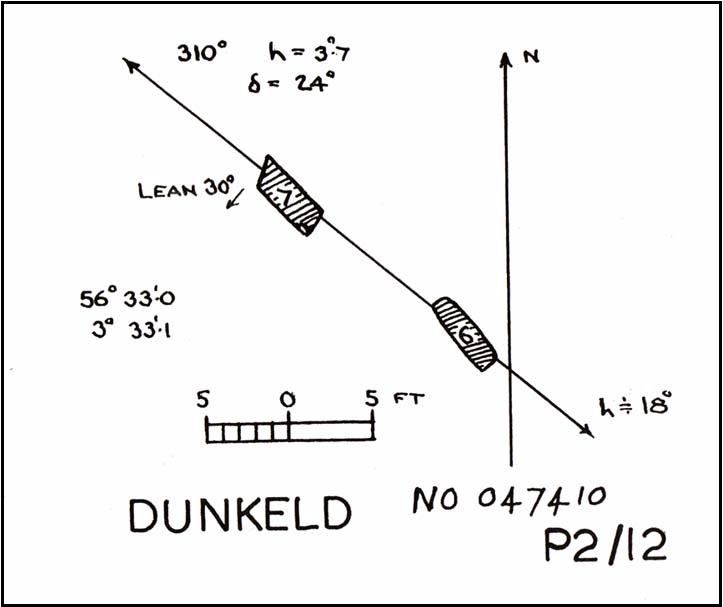

Little else was said of the two stones for many years and, to my knowledge, no real excavation has been undertaken here. But when Alexander Thom (1990) visited the site he found that,

“This two stone alignment showed the midsummer setting sun. The south stone may possibly, by itself, have shown the setting Moon at major standstill.”

Aubrey Burl’s description of the stones was succinct and echoed much of what Coles had said decades earlier, telling:

“Two very large stones stand only 9 feet (2.7m) apart in an unusually closed-in environment for a Perthshire pair. The ground rises very steeply to the east. To the west the stones overlook the valley of the River Tay.

“Both are of local quartzoze schist and are ‘playing-card’ in shape. As usual it is the westernmost stone that is taller, 7ft 2in (2.2m) in height. Its peak tapers almost to a point. Conversely, its partner is flat-topped and only 4ft 9in (1.5m) high. The pairing of such dissimilarly shaped stones has led to the interpretation of them as male and female personifications.”

Burl’s latter remark thoughtfully recognises that such animistic qualities are found in many other cultures in the world and this ingredient was also an integral part of early peasant notions in Britain; therefore such ingredients are necessities to help us understand the nature and function of megalithic sites. We must be cautious however, not to fall into the increasingly flawed modern pagan notion of such male and female ‘polarizations’, nor the politically-correct sexist school of goddess ‘worship’ and impose such delusions upon our ancestors, whose worldviews had little relationship with the modern pagan goddess fallacies, beloved of modern Press, TV shows and pantomime festival displays.

Folklore

In Elizabeth Stewart’s history of Dunkeld, she narrates the tale told by an earlier historian who told that,

“these two upright stones at the Doo’s Nest, but says they are supposed to mark the graves of two Danish warriors returning from the invasion of Dunkeld.”

References:

Burl, Aubrey, From Carnac to Callanish, Yale University Press 1993.

Coles, Fred, “Report on Stone Circles Surveyed in Perthshire – Northeastern Section,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 42, 1908.

Stewart, Elizabeth, Dunkeld – An Ancient City, Munro Press: Perth 1926.

Thom, A., Thom, A.S. & Burl, Aubrey, Stone Rows and Standing Stones – 2 volumes, BAR: Oxford 1990.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.