Wayside Cross: OS Grid Reference – TQ 33781 89561

Also known as:

The Cross is on the east side of the A10 Tottenham High Road, on the traffic island at the Monument Way Junction.

Archaeology & History

One of the earliest records of what was called the “hie crosse” is contained in a court-roll of 1456. It was at that time a wooden wayside cross, but there are hints that its origins may go back to Roman times. The Cross is next to what was the southern end of Ermine Street, built by the Romans where there was no pre-existing roadway and described as the most important thoroughfare in Britain: built to give direct communication to the main centres of the military occupation at Lincoln and York. Writing of Roman land survey marks, the now discredited early 20th century Middlesex historian Sir Montagu Sharpe (1932) thought Tottenham Cross possibly marked an earlier (i.e. Roman) stone, although no archaeological evidence has been found to support this. As it was next to Ermine Street it could equally have been a milestone or ceremonial pillar. After the Romans left it may have become a local heathen shrine which, with the coming of Christianity, was ultimately replaced by a wooden cross—but this is speculation, and we will probably never know why and when the original cross was placed where it was.

Originally in the historic County of Middlesex, the settlement of Tottenham surrounding the Cross was known from mediaeval times to the 19th century as ‘Tottenham High Cross’. Local historian William Robinson writing prior to 1840 thus describes the Cross:

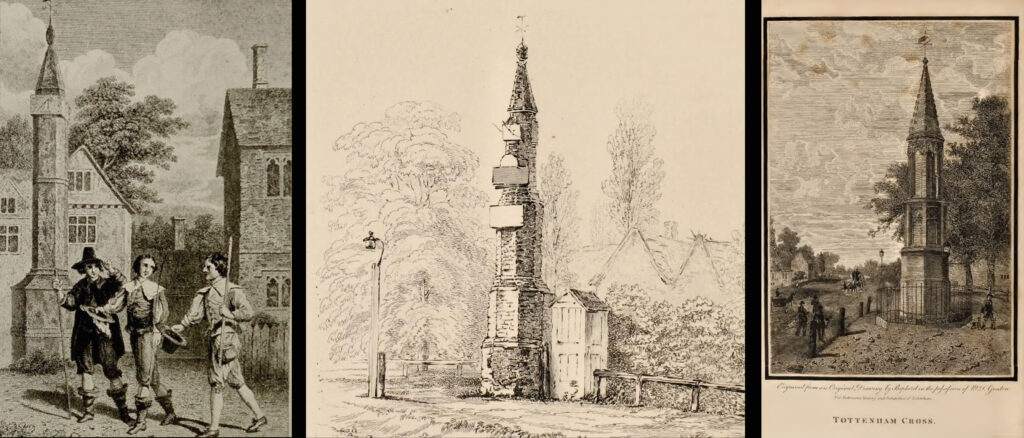

“About the year 1580, a column of wood was standing, with a square sheet of lead on the top to throw off the water, supported by four spurs: these, being decayed and rotten, were taken down, about the year 1600, by Dean Wood, Dean of Armagh, who at that time resided in a house on the east side of it, and who erected on its site an octangular brick column, pointed at the top and crowned with a weathercock, and the initials of the four cardinal points, and under the neckings, small crosses, which were called tau-crosses, according to the true cross or Greek letter T.

“Tottenham High Cross, as it appeared in 1788, was an octangular brick pillar, divided into four stories, viz.: a double plinth, first portion of the pillar; second portion, of the same; and a pinnacle; each plinth and story rendered distinct one from the other by certain appropriate mouldings ; and the whole design appeared without any kind of ornament, pointed at the top and crowned with a weathercock. The Cross having fallen into decay, several of the inhabitants of the parish entered into a subscription, in the year 1809, for the purpose of putting it into a proper state of repair, and about the sum of £300. was raised. It was accordingly repaired, and covered with Parker’s cement. The octangular plan, and the proportions of the Cross in its four stories, have not been departed from ; but in other respects it is a new work ; some of the decorations seem to be formed from the exterior and interior of the chapel of Henry VIII; the double plinths or pedestals are as plain as before, but the intermediate mouldings are new; the first portion of the pillar consists of angular pilasters at each cant done with a pointed head; compartment of five turns, connecting itself with another compartment; above it diamonded, with a shield containing an imitation of the black letter. As there are eight faces to the upright, of course there are as many shields, each bearing a letter of the same cutting, beginning at the west face, TOTENHAM: in consequence of there being but eight shields, one of the T’s in the spelling has been necessarily dispensed with. The mouldings between this story and the second are worked into an entablature, with modern fancy heads and small pieces of ornaments alternately set at each angle.

“Second story—small buttresses at the angles of the octagon, with breaks and pinnacles, but no bases. The face of each cant has a compartment embellished with an ogee head, backed with narrow pointed compartments. The mouldings between this story and the pinnacle, making out a fourth story, give, at each angle, crockets, and its termination is with a double finial, but not set out in geometrical rule to the crockets below : there is at the top a vane, with N. E. W. S. The base is surrounded with a neat iron railing on Portland stone curb. The date at which these alterations were made is not placed in any conspicuous part of the structure.”

The craftsman who carried out the modernisation was a Mr. Bernasconia, working to the designs of a Mr. Shaw. Not everyone was pleased by the transformation. A regular contributor identified only as ‘An Architect’ made these caustic comments in the November 1809 edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine:

“Tottenham High Cross has this summer been covered over with Compo: it previously bore a simple appearance, but is now rendered of a very rich and elaborate cast, doing away in the first instance the Architectural history of the erection; and allowing it possible that there might once have been on the spot an Eleanora Cross, holding in contempt, by a want of due imitation, the characteristic style of decoration prevailed at at the time of the Queen’s demise. But according to the system of our Professional innovators, to destroy a sacred relick of antiquity, and to restore it as it is called, upon a model quite in a different style and nature, is one and the same thing. “Any thing is Gothick.”

“….Surveyed November 1809. Entirely covered with the proclaimed everlasting stuff, Compo; a stuff now the rage for trowelling over our new buildings, either on the whole surface, or in partial daubings and patchings; it is used in common with stone work, for instance, on an arcade, half one material, half the other; “ making good,” as it is called (abominable expedient) the mutilated parts of Antient Structures, there sticking on until it reverts (after exposure to the air for three or four years, more or less) to its first quality, dirt and rubbish, and then is seen no more….

“Provided this Compo effort had been advanced on any other occasion, and on any other piece of ground, where no piece of Antiquity was to become the spoil, such as an object to mark the centrical point of three or four counties, a general standard of miles or any other common document for the information or amusement of travellers, all would have been well, and some praise might have been bestowed, for its tolerable adherence to the above style, if not for the material wherewith it is made up. But as nothing of this sort will come in aid of the innovators, and only the barefaced presumption, “ alter or destroy, what was,” is to be encountered, let the detail of parts, put this matter to issue….”

Folklore

The Cross stood in front of the Swan Inn, a place frequented by fishing writer Izaak Walton in the 1640s when he would go to fish in the nearby River Lea. In 1653 he published The Compleat Angler describing his fishing activities in the classical form of a philosophical dialogue between him as ‘Piscator’ and ‘Venator’ (hunter) and other passing characters, starting and ending his adventures at the High Cross. The 1759 edition of Compleat Angler contains the earliest illustrations of the Cross, with some slight artistic licence, by Samuel Wale.

Afterword

As the Cross now stands in the maelstrom of North London’s traffic, it is worth recalling American traveller Nathaniel Carter’s 1825 observation when travelling north from London:

“Passing Tottenham Cross, we entered a rich agricultural country, possessing the usual charms of English landscape.”

References:

- An Architect (pseud.) – Architectural Innovation No. CXXXIX – The Gentleman’s Magazine, November 1809

- Anonymous – Tottenham High Cross, The Gentleman’s Magazine, April 1820

- Blair, John, The Church in Anglo Saxon Society, Oxford University Press 2005

- Carter, Nathaniel Hazeltine, Letters From Europe..in 1825 ’26 & ’27, G & C & H Carvill, New York, 1829

- Margary, Ivan D., Roman Roads in Britain, 3rd Ed., John Baker: London 1973.

- Robinson, William, The History & Antiquities of the Parish of Tottenham, 2nd Ed., Nicholls & Son, W. Pickering, W.B. Hunnings: London 1840.

- Sharpe, Montagu, Middlesex in British, Roman & Saxon Times, 2nd Ed., Methuen: London 1932.

- Walton, Izaak, The Compleat Angler, Facsimile of the 1st Ed., containing illustrations from the 2nd US edition by John Major, No imprimatur, 1907.

© Paul T Hornby 2020

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.