Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 12233 46342

Also Known as:

- Carving no.114 (Hedges)

- Carving no.267 (Boughey & Vickerman)

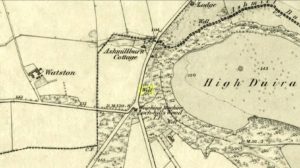

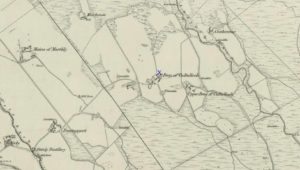

From Ilkley walk up to the White Wells and follow the footpath behind it up to the cliffs, up the stone steps and onto the moor itself. Once you’ve climbed the steps, walk uphill onto the moor for 100 yards, then turn right up a small path for another 80 yards until you reach the large Coronation Cairn with its faint cup-and-ring stone. From here there are two paths heading west: take the higher of the two for just 30 yards where a small group of rocks are by the path-side on your right. The curiously-shaped ‘upright’ one is the stone in question. You’ll see it.

Archaeology & History

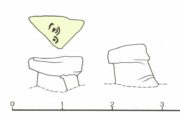

Found high up on top of an oddly-shaped stone, somewhat like an anvil or small table (hence the name, courtesy of Jonathan Warrenberg), is carved a slightly worn, incomplete cup-and-double-ring. This aspect of the design is the one that stands out the most; but you’ll also see a cup-and-half-ring there too.

The carving seems to have been described for the first time in John Hedges (1986) survey (though I may be wrong), who described an additional feature to the design, saying:

“Small grit rock in possible cairn material, cut all round as if one pedestal, top surface triangular, sloping slightly SW to NE, overlooking Wharfe Valley, in grass and crowberry. Large cup with two vestigial rings, second large cup with vestigial ring. Possible third ring of corner edge (hewn off). Recent carving of initials spoils original carving.”

His description of the stone being “in possible cairn material” doesn’t seem true – although a number of petroglyphs are associated with cairns of varying sizes. Several other carvings can be found close to this one.

In Boughey & Vickerman’s (2003) later survey, they copy Mr Hedges earlier description, but with less detail.

The view from this stone is quite impressive. Even with the minor tree cover that would have existed when this carving was done, you’d still have clear views up and down the winding wooded valley that was carved by the River Wharfe. The moors to the north at Denton and Middleton with their own petroglyphic abundance could be chanted at with ease from here when the winds sleep. Tis a good spot to sit… if you’re lucky enough to get some silence…

References:

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

Links: The Table Stone carving on The Megalithic Portal

Acknowledgments: Huge thanks to Jonathan Warrenberg for the use of his photos in this site profile – and also due credit for giving the stone its modern title. 🙂

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian