Holy Well (destroyed): OS Reference – TQ 3370 8999

Also Known as:

- Old Tottenham Well

- St. Eloy’s Well

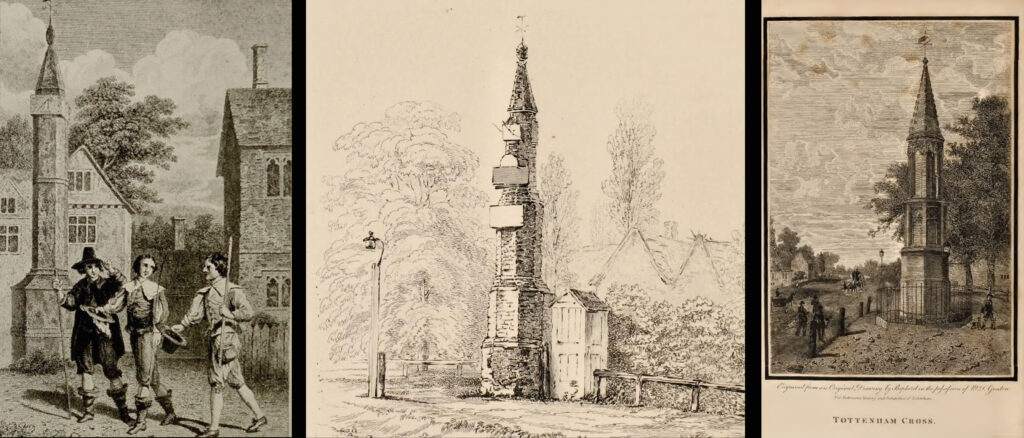

The site of the well, which was in the historic county of Middlesex, appears to have been on the west side of the present Moorefields Road just north of the junction with St Loy’s Road. The OS reference is an approximation. The restored circular well house to the south of the High Cross at the High Road – Philip Lane junction now popularly known as ‘The Old Well’ or ‘The Old Pump’ by Tottanham Green has been referred to as being ‘St Eloy’s Well’ but this is not the historic well described in this profile.

Archaeology & History

The well was still in existence in 1876, but by the time of the revision of the OS map around 1894, it had been destroyed following building of the Great Eastern Railway’s Enfield branch line and the construction of terraced housing along the new St Loy’s Road.

So where was the well? The 1873 6″ OS map shows a field on parts of which the railway line and St Loy’s Road are now built, and a small area of water is shown in this field which is the likely position of St Loy’s Well on the eve of its destruction, when it was described as a dirty pool of water full of mud and rubbish. If this was the position of the well then it has now been completely built over…

It was described by Robinson in his 1841 History of Tottenham as being:

‘..in a field….on the western side of the High Road…surrounded by willows…it is bricked up on all sides, square and about 4 feet deep..’ ‘ In Bedwell’s time [it was]…always full of water, but never running over; the water of which is said to exceed all other near it.’.. ‘the properties of the water are similar to the water of the Cheltenham springs’.

Thomas Clay ‘s 1619 map of Tottenham, illustrated in Robinson’s book shows a field north west of Tottenham High Cross called ‘Southfeide at St Loys’. The Tottenham historian Wilhelm Bedwell described the well in 1631 as:

‘“nothing else but a deep pit in the highway, on the west side thereof;”….”it was within memory cleaned out, and at the bottom was found a fair great stone, which had certain letters or characters on it; but being broken or defaced by the negligence of the workmen, and nobody near that regarded such things, it was not known what they were or meant.’

This fair great stone with its ‘certain letters or characters that no one knew what they were or meant’ is intriguing especially in view of the well’s proximity to the Roman Ermine Street (Now the High Street). Were those mysterious characters spelling out an undecipherable Latin inscription on a Roman stone? We shall never know, but it hints at a pre-Christian origin or veneration of the well. Another hint is that before the Reformation there was nearby a chapel of St Eloy known as the Offertory*, which may have been originally built to ‘Christianise’ a pre-existing heathen sacred spring. The Roman origins of the well are also hinted at (probably erroneously) by W.L. Bowles in 1830, writing of a ‘Druidical Tour’ that one Sir Thomas Phillipps undertook on the continent, first quoting Phillipps before adding his own conclusion:

‘“Near Arras in France, are found the mount of St. Eloi and the very name of a place, Tote. I have no doubt Druidical remains will be found there, if this be not the very country of Carnutes.”

Now let me observe, that Tote is Taute —Tot—Thoth, latinized into Tewtates by Lucan, &c. the chief deity of the Celts. St. Eloi is neither more nor less than the Celtic word Sul, turned into the Greek the Sun; and Elios, turned into the Catholic St. Eloi, as at Tottenham, Middlesex, anciently Tote-ham, the ham of Taute or Tent, where is also the sacred well of St. Eloi, or ‘Helios’, the Sun !’

Saint Eloi / Eloy /Loy / Eligius, is the patron saint of those who work in the alchemists’ metal of the sun – goldsmiths! He is also the patron saint of blacksmiths, farriers, and all who earned their livings from horses, and lived from around 588 to 660 to become Bishop of Noyon and the evangelising apostle for much of modern day Belgium. His feast day is 1st December, and he had a widespread cult in mediaeval Europe, including England. In addition to being a healing well for humans, one writer hints that the well’s waters may have been employed for healing horses…they certainly would have drunk from it with its proximity to what is now the High Street.

Around 1770, an artist called Townsend (the sources are unsure as whether it was a Mrs or Mr) produced a romanticised drawing of the well, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1770-1. It depicts a hermit beside the well (the Hermitage of St Anne stood to the south of High Cross prior to the Reformation) receiving an offering from a lady. It was engraved and sold as a print, and may be the only image of the well before its demise.

Folklore

In 1819 – 20, John Abraham Heraud wrote a poem about St Loy’s Well, set in the time of St. Edward the Martyr, (the late 970s), entitled ‘ Stanzas in the Legend of St Loy‘ of which the most relevant verses are;

‘TOTEHAM! the Legend of thine olden day,

To the last note hath on thine echoes died;

But the Bard’s soul still lingers o’er the lay,

To muse upon thy transitory pride

The pride of times that hath been — blank and void—

When all was Nature, big with many a song

Of Chivalry and Fame, with Love allied—

But Time both changed the scene — now houses throng

Where once was solitude — and people crowd along.Where now thy WOOD, that spread its misty shade

O’er twice two hundred acres? — past away!

And vain its PROVERB, as the things that fade,

Earth, sun, moon, stars, that change as they decay!

The lonely CELL, the tenor of the lay,

Its grove, which hermit tendance loved to rear;

And, St. LOY, mouldering to Time’s gradual sway,

Thy rites, thy OFFERTORY disappear;—

Forgot thy SPRING OF HEALTH no votary worships there!Forgot, neglected — still my harp shall dwell

On thee, thou blest BETHESDA of ST. LOY!

As Fancy muses o’er the vital WELL

On years of storied yore, with grief and joy,

Exults they were — weeps Truth should e’er destroy!

Thrice I invoke the Spirit of the Stream

With charm she may not question, or deny,

And, like a Naiad, o’er the watery gleam

She rises to my voice, and answers thus the theme:— ‘

Heraud wrote a further poem mentioning the well, his ‘Tottenham‘ of 1820, the relevant verse being:

‘St. Loy! here is this fountain—emblem pure

Of chaste unostentatious charity—

Never in vain intreated, ever sure ;

Yet o’er the marge thy waters fair and free

Ascend not, overflowing vauntingly,

But in thy bounty humble as unfailing,

In grief, disease, and sickness, visit thee.

But part in joy, changed by thy holy healing

To manhood, strength, and life, thy far renown revealing.

There is thy offertory, and thy shrine,

Simple, inartificial ; nor of fame,

Nor any honour, save that it is thine,

And all its glory centres in thy name !’

*Footnote – Brian Spencer’s book on mediaeval pigrim badges recovered by archaeologists in London refers (p222) to a distinct ‘London pattern’ of St Eloi badge – is this a hint that the Offertory was a local shrine to St Eloi where such badges were sold to pilgrims? Further research is needed to try to verify this speculation.

References:

- Baker, T.F.T. & Pugh, R.B. (eds.), Victoria County History – A History of the County of Middlesex, volume 5, VCH: London 1976.

- Bowles, W.L., Tottenham High Cross, Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol C, April 1830.

- Breeze, Andrew, Chaucer, St Loy and the Celts, Reading Medieval Studies 17, 1991.

- Foord, Alfred Stanley, Springs, Streams and Spas of London: History and Association, T. Fisher Unwin: London 1910.

- Heaword, Rose, “Holy Wells and Lost Waters,” in London Earth Mysteries Journal, 2, 1990.

- Heraud, John Abraham, Stanzas in the Legend of St Loy, …

- Hope, Robert Charles, Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England, Elliott Stock: London 1893.

- Robinson, William, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Tottenham, Nichols & Sons: London 1840.

- Spencer, Brian, Pilgrim Souvenirs And Secular Badges – Boydell Press in association with Museum of London, new edition, 2010

- Sunderland, Septimus, Old London Spas, Baths and Wells, John Bale: London 1915.

- Thornbury, Walter & Walford, Edward, Old and New London – volume 5, Cassell: London 1878.

- Walford, Edward, Old and New London, Vol. V, Cassell, Petter & Galpin: London, 1878.

Links:

- St. Eloy’s Well on The Megalithic Portal

© Paul T. Hornby 2020