Cup-and-Ring Stones: OS Grid Reference – SE 11471 47289

Also Known as:

- Carving no.99 (Hedges)

- Carving no.229 (Boughey & Vickerman)

- Panorama Rock

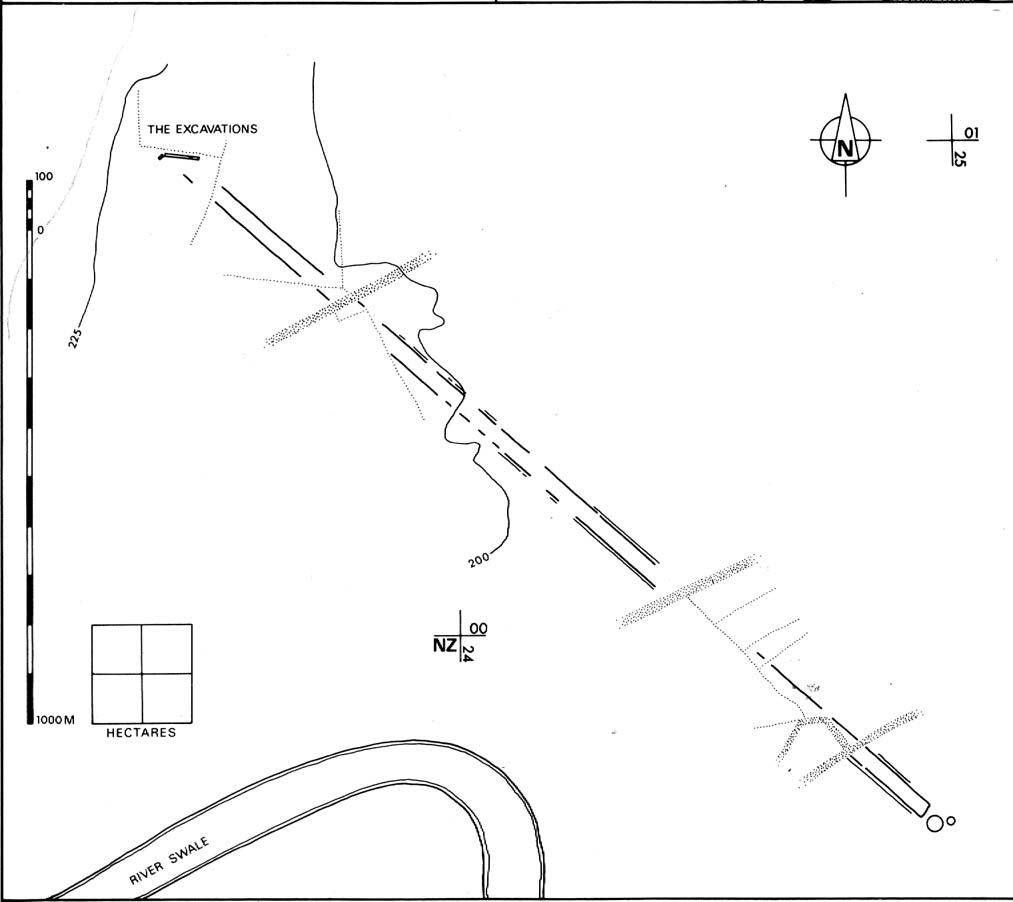

Come out of Ilkley/bus train station and turn right for less than 50 yards, turning left up towards White Wells. Go up here for less than 100 yards, taking your first right and walk up Queens Road until you reach the St. Margaret’s church on the left-hand side. On the other side of the road, aswell as a bench to sit on, a small enclosed bit with spiky railings all round houses our Panorama Stones.

Archaeology & History

There were originally ten or eleven carvings that made up what have been called the Panorama Stones and the position they are presently housed in this awful fenced section wasn’t their original home. They used to live a half-mile further up from here, on the moorland edge, just in the woodland at the back of the small Intake Reservoir in the appropriately named Panorama Woods. But in 1890, one Dr. Little — medical officer at Ben Rhydding Hydro — bought the stones for £10 from the owner of the land at Panorama Rocks, as the area in which the stones lived was due to be vandalized and destroyed. Thankfully the said Dr Little was thoughtful and as a result of his payment he had some of the stones saved and moved into the position where they live today. However, as a result of the stones being transported closer to Ilkley, the largest of the carvings was damaged and broken in two pieces on its journey, but the good doctor and his mates restored the rock as best they could before sitting it down in the caged position where it remains to this day.

Thankfully there remain a couple of carved rocks in situ in the trees near where these companions originally came from — though they’re completely overgrown. We uncovered these carvings (one of which was quite ornate) when we were children, but this is now overgrown again and hidden from the eyes of the casual forager. The original position of these carvings was obviously an important feature to our ancestors, but such aspects are of little relevance to industrialists and those lacking sacred notions of the Earth. The same geological ridge on which the Panorama Stones were originally found, stretching west along the moor edge from here, possesses a number of other fascinating carvings, not least of which is our Swastika Stone.

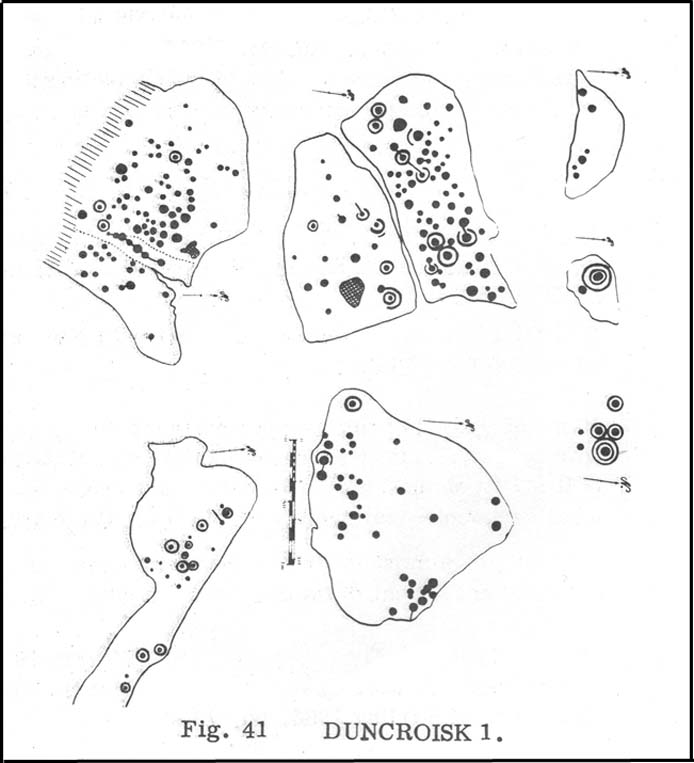

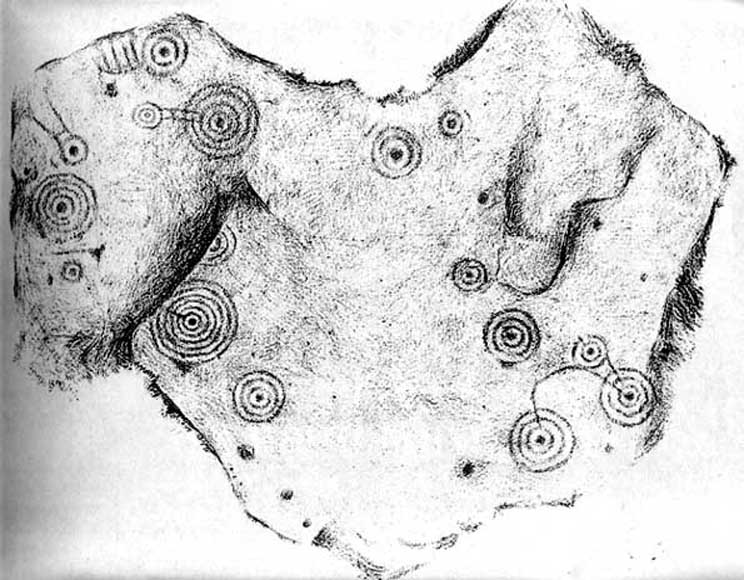

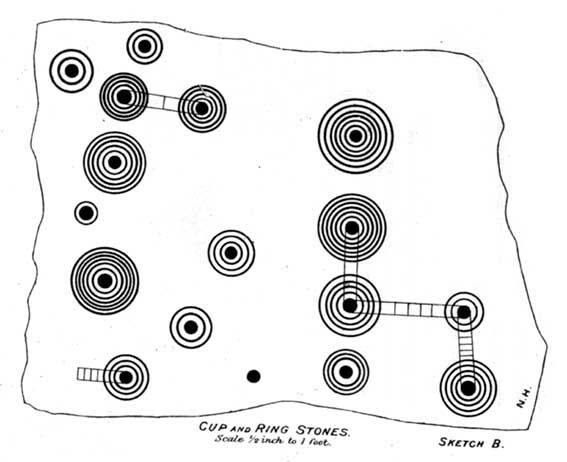

It seems they were all first recorded by one J. Thornton Dale, who did some fine illustrations of each stone, which were then collected and organized by a certain Dr. Call of Ilkley in 1880 as a ‘Collection of fourteen drawings of cup-marked rocks.’ These were on file at Ilkley Library (or at least used to be!) and as they’ve not been published previously, I think they need to be retrieved from their dusty shelves and stuck on TNA where they certainly belong! As we can see in Dale’s illustration — etched shortly after the stone was first discovered — much of the detail of the multiple-rings and some of the curious ladder-like motifs were noted (though not all).

Around the same time in 1879, the renowned archaeologist J. Romilly Allen did an early article on the carved stones of Ilkley Moor, selecting the Panorama Stones as one site in his essay. He was very fortunate in getting an early look at the carvings here and gave the following lucid account:

“The Panorama Rock lies one mile south-west of Ilkley, and from a height of 800ft above the sea commands a magnificent view over Wharfedale and the surrounding country. About 100 yards to the west of this spot appears to be a kind of rough inclosure, formed of low walls of loose stones, and within it are three of the finest sculptured stones near Ilkley. They lie almost in a straight line east and west, the first stone being 5ft from the second, and the second 100ft from the third. The turf was stripped from the first a few years ago, and its having been covered up so long probably accounts for the sculpture being in such good preservation. It measures 10ft by 7ft, and is im- bedded so deeply in the ground that its upper horizontal surface scarcely rises above the level of the surrounding heath. The sculpture consists of twenty-five cups, eighteen of which are surrounded with concentric rings, varying from one to five in number. The most remarkable feature in the design is the very curious ladder-shaped arrangement of grooves by which the rings are intersected and joined together. I do not think that this peculiar type of carving occurs anywhere else besides near Ilkley. The second stone is of irregular shape, measuring 15ft by 12ft, and supporting a smaller stone of triangular shape 6ft long by 4ft broad. Both upper and under stone are covered with cups and rings, but the sculptures have suffered much from exposure. The superimposed block has eleven cups, two of which are surrounded by single rings. The under stone has forty-two cups, nine of which have rings. Amongst these are two unusually fine examples, one has an oval cup 5in by 4in, surrounded by two rings, the diameter of the outer ring being 1ft 3in. Another has a circular cup 3in diameter and five concentric rings, the outer ring being 1ft 5in across. The third and most westerly stone of the group measures 10ft by 9ft, and lies almost horizontally, having its face slightly inclined. On it are carved twenty-seven cups, fourteen of which have concentric rings round them. Some of the cups have connecting grooves and three have the ladder-shaped pattern before referred to. Several stones near have cup marks without rings.”

When Harry Speight (1900) visited these stones a few years later he echoed much that Romilly Allen had said previously, also commenting on how on certain parts of the carving, “the rings enclosing each cup are connected with ladder-like markings.” (my italics, PB) These “ladders” were even mentioned in a speculative but inaccurate essay by Nathan Heywood (1888) in a paper for the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society. Equally important was a description of the site when members of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society visited the Panorama Stones in 1884, and Rev. A.C. Downer (1884) described this “most important group” of stones, saying that

“Near the Panorama Rock are three large masses of ironstone close together, and averaging ten to twelve feet across each way, the horizontal surface of which are covered with cups and rings, and two of these stones have also a peculiar arrangement of grooves somewhat resembling a ladder in form.”

Modern Folklore

Despite this and other descriptions, in recent times local archaeologist and rock art student Gavin Edwards has propounded the somewhat spurious notion that the ladders and perhaps other parts of the Panorama Stone carvings have a recent Victorian origin, executed by a local man by the name of Mr Ambrose Collins. Edwards took this silly idea to the Press, thinking he’d found something original, following a recovery of some notes from the Ilkley Gazette newspaper (earlier archaeologists had already explored this, which he should have been aware of), in which was stated that the said Mr Collins told other people in the Ilkley area that he was carving some of the old stones on the moors nearby. Now we know that Collins did this (we have at least 3 examples of his ‘rock art’ in our files), but he wasn’t allowed to touch the Panorama Stones!

However, despite Gavin Edwards’ theory, it is clear that Ambrose Collins was not responsible for any additional features on the Panorama Stones: an opinion shared by other archaeologists and rock art specialists. Edwards’ theory can be clearly shown as incorrect from a variety of sources (more than the examples I give here).

In no particular order…there was an early photo of the main stone (above), taken sometime in the late-1870s by Thomas Pawson of Bradford which shows, quite clearly, some of the faded “ladder” motifs on the rock in question while the stone was still in situ. There is also an additional and important factor that Edwards has seemingly ignored, i.e., that neither J.Romilly Allen, Harry Speight, members of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, nor any of their contemporaries made any comments regarding additional new motif elements carved onto these rocks when they visited the carvings at the period Edwards is suggesting Collins did his additions — which such acclaimed historians would certainly have mentioned. Mr Edwards theory, as we can see, was a little lacking in research. Considering only these small pieces of evidence, the pseudoscientific nonsense of the Victorian carving theory can safely be assigned to the dustbin!

If however, we do use Mr Edwards’ reasoning: take a look at the modern “accurate” drawing of this carving in Boughey & Vickerman’s (2003) book—which actually, somehow, misses elements of the carving that are clearly shown in Mr Pawson’s 1890’s photo and are still visible to this day! What are we to make of that? Have these modern folk been at it with the sand paper!? We can only conclude that these simple errors show a lack of research. The most worrying element here is that a local archaeologist can make such simplistic errors in his analysis of prehistoric and Victorian carvings without checking over publicly accessible data. Even more disconcerting was the fact that he was running Ilkley’s local prehistoric rock art group!

However, we cannot dismiss out of hand the words of the said Ambrose Collins in his proclamation of carving stones on the moors, as there is clear evidence that he did a replica of the Swastika Stone on rocks near the original site of the Panorama Stones. The carving he did is very clearly much more recent. We have also found one carving with Collins’ initials — ‘A.C.’ — carved on it and the date ‘1876’ by its side.

And although we can safely dismiss the Edward’s Theory about the Panorama Stones “ladders”, we may need to reconsider a number of other carvings on Rombald’s Moor as potentially Victorian in nature using the rationale Edwards proclaimed. For example — and using the disproved Edwards Theory — when we look at Romilly Allen’s drawing of the famous Badger Stone (from the same essay in which his image of the Panorama Stone is here taken), much of the carving as it appears today was not accounted for in the drawing. We can also look selectively at many other cup-and-rings on these moors and find discrepancies in form, such as with the Lattice Stone on Middleton Moor, north of Ilkley, or the eroded variations on the Lunar Stone. We have to take into consideration that some may have been added to; but more importantly, we must also be extremely cautious in the movement between our idea and the authenticity of such an idea. It is a quantum leap unworthy of serious consideration without proof. (though the example of the Lattice Stone has a markedly different style and form to the vast majority of others on the moors north and south of here. Summat’s “not quite right” with that one and the comical Mr Collins might have had his joking hands on that one perhaps…)

One very obvious reason that a number of the cup-and-ring carvings were not drawn correctly by historians and archaeologists alike, would be the weather! Archaeologists are renowned for heading for cover when the heavens open, quickly finishing their jottings and running for cover — and this would obviously have been the case with some of the drawings, both early and modern. Bad eyesight and poor lighting conditions is also another reason some of the carvings have been drawn incorrectly, as a number of modern archaeology texts — including a number in Boughey & Vickerman’s (2003) book — illustrate to any diligent student!

There is still a lot more to say about this fascinating group of carvings, which I’ll add occasionally as time goes by. And if anyone has any good clear photos of the stones showing the intricate carved designs that we can add to this profile, please send ’em in (all due credit and acknowledgements will be given).

…to be continued…

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “The Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,” in Journal of British Archaeological Association, volume 35, 1879.

- Bennett, Paul, The Panorama Stones, Ilkley, TNA: Yorkshire 2012.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Leeds 2003.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Downer, A.C., “Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Association,” in Leeds Mercury, August 28, 1884.

- Hadingham, Evan, Ancient Carvings in Britain, Souvenir Press: London 1974.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Heywood, Nathan, “The Cup and Ring Stones of the Panorama Rocks”, in Trans. Lancs & Cheshire Anti. Soc.: Manchester 1889.

- Hotham, John Paul, Halos and Horizons, Hotham Publishing: Leeds 2021.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to the staff at Ilkley Library for their help in unearthing the old drawings and additional references enabling this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian