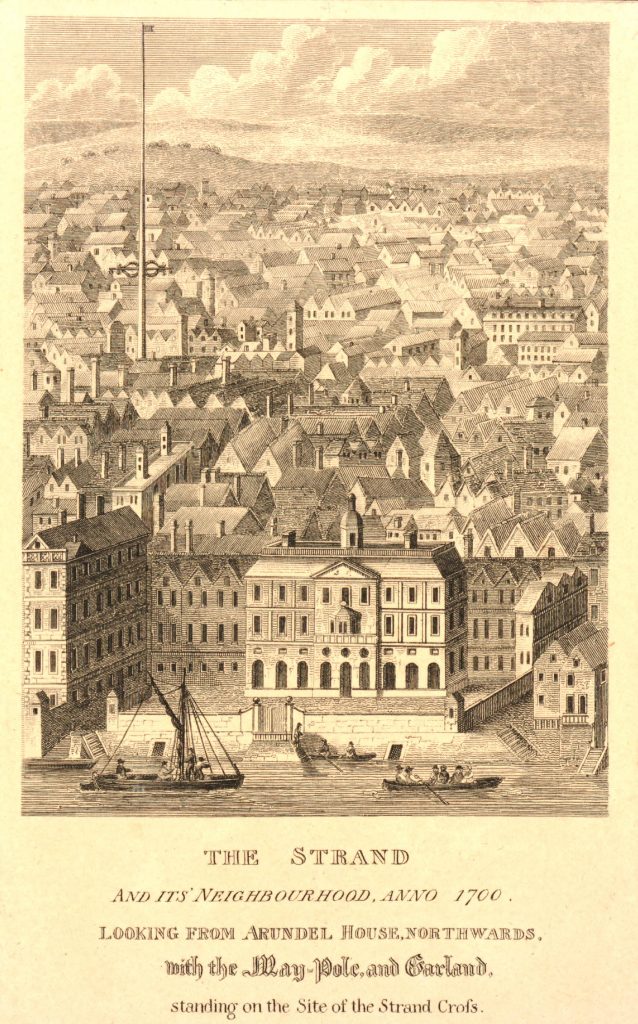

In A.R. Wright’s (1938) account of it, he called this “the most famous maypole in England” and it stood taller than even the great maypole that’s still raised at Barwick-in-Elmet, in Yorkshire.

In Edward Walford’s (1878) massive tome, he gave us perhaps the best and most extensive account of the site, telling:

“The Maypole, to which we have already referred as formerly standing on the site of the church of St. Mary-le-Strand, was called by the Puritans one of the “last remnants of vile heathenism, round which people in holiday times used to dance, quite ignorant of its original intent and meaning.” Each May morning, as our readers are doubtless aware, it was customary to deck these poles with wreaths of flowers, round which the people danced pretty nearly the whole day. A severe blow was given to these merry-makings by the Puritans, and in 1644 a Parliamentary ordinance swept them all away, including this very famous one, which, according to old Stow, stood 100 feet high.

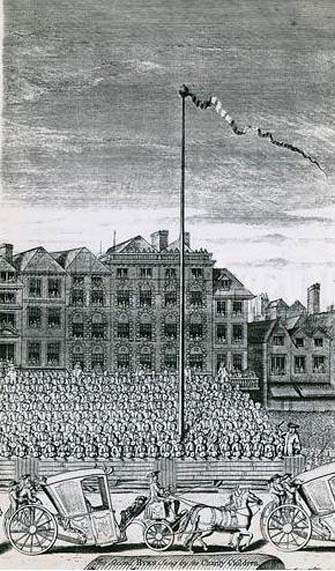

On the Restoration, however, a new and loftier one was set up amid much ceremony and rejoicing. From a tract printed at the time, entitled ‘The Citie’s Loyaltie Displayed,’ we learn that this Maypole was 134 feet high, and was erected upon the cost of the parishioners there adjacent, and the gracious consent of his sacred Majesty, with the illustrious Prince the Duke of York:

“This tree was a most choice and remarkable piece; ’twas made below bridge and brought in two parts up to Scotland Yard, near the king’s palace, and from thence it was conveyed, April 14, 1661, to the Strand, to be erected. It was brought with a streamer flourishing before it, drums beating all the way, and other sorts of musick. It was supposed to be so long that landsmen could not possibly raise it. Prince James, Duke of York, Lord High Admiral of England, commanded twelve seamen off aboard ship to come and officiate the business; whereupon they came, and brought their cables, pullies, and other tackling, and six great anchors. After these were brought three crowns, borne by three men bareheaded, and a streamer displaying all the way before them, drums beating and other musick playing, numerous multitudes of people thronging the streets, with great shouts and acclamations, all day long. The Maypole then being joined together and looped about with bands of iron, the crown and cane, with the king’s arms richly gilded, was placed on the head of it; a large hoop, like a balcony, was about the middle of it. Then, amid sounds of trumpets and drums, and loud cheerings, and the shouts of the people, the Maypole, ‘far more glorious, bigger, and higher than ever any one that stood before it,’ was raised upright, which highly did please the Merrie Monarch and the illustrious Prince, Duke of York; and the little children did much rejoice, and ancient people did clap their hands, saying golden days began to appear.”

A party of morris-dancers now came forward, “finely decked with purple scarfs, in their half-shirts, with a tabor and a pipe, the ancient music, and danced round about the Maypole.”

The setting up of this Maypole is said to have been the deed of a blacksmith, John Clarges, who lived hard by, and whose daughter Anne had been so fortunate in her matrimonial career as to secure for her husband no less a celebrated person than General Monk, Duke of Albemarle, in the reign of Charles II., when courtiers and princes did not always look to the highest rank for their wives.

…Newcastle Street, at the north-east corner of the church of St. Mary-le-Strand, was formerly called Maypole Alley, but early in the last century was changed to its present name, after John Holles, Duke of Newcastle, the then owner of the property, and the name has been transferred to another place not far off. At the junction of Drury Lane and Wych Street, on the north side, close to the Olympic Theatre, is a narrow court, which is now known as Maypole Alley, near which stood the forge of John Clarges, the blacksmith, alluded to above as having set up the Maypole at the time of the Restoration.

As all earthly glories are doomed in time to fade, so this gaily-bedecked Maypole, after standing for upwards of fifty years, had become so decayed in the ground, that it was deemed necessary to replace it by a new one. Accordingly, it was removed in 1713, and a new one erected in its place a little further to the west, nearly opposite to Somerset House, where now stands a drinking fountain. It was set up on the 4th of July in that year, with great joy and festivity, but it was destined to be short-lived. When this latter Maypole was taken down in its turn, Sir Isaac Newton, who lived near Leicester Fields, bought it from the parishioners, and sent it as a present to his friend, the Rev. Mr. Pound, at Wanstead in Essex, who obtained leave from his squire, Lord Castlemaine, to erect it in Wanstead Park, for the support of what then was the largest telescope in Europe, being 125 feet in length. It was constructed by Huygens, and presented by him to the Royal Society, of which he was a member. It had not long stood in the park, when one morning some amusing verses were found affixed to the Maypole, alluding to its change of position and employment. They are given by Pennant as follows:

“Once I adorned the Strand,

But now have found

My way to Pound

On Baron Newton’s land;

Where my aspiring head aloft is reared,

T’ observe the motions of th’ ethereal Lord.

Here sometimes raised a machine by my side,

Through which is seen the sparkling milky tide;

Here oft I’m scented with a balmy dew,

A pleasant blessing which the Strand ne’er knew.

There stood I only to receive abuse,

But here converted to a nobler use;

So that with me all passengers will say,

‘I’m better far than when the Pole of May.'”

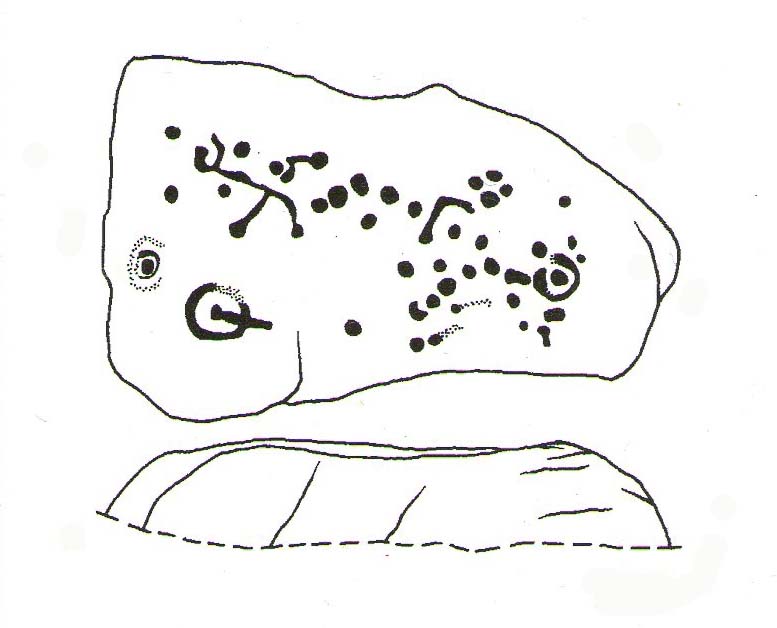

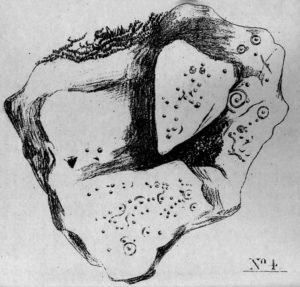

The nature of the maypole (and the nearby cross, it has to be said), may have been representative of an omphalos in early popular culture (before the christians of course)—which would put the original ritual function of the place far far earlier than is generally considered. This is something that Laurence Gomme (1912) propounded in one of his London works and cannot be discounted.