Standing Stones: OS Grid Reference – NS 53269 80727

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 44605

- Dungoiach

- Duntreath

Getting Here

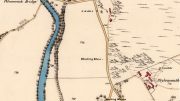

Approaching Dumgoyach Hill

You can either find your way to Duntreath Castle on the western edges of Strathblane and walk SW straight up the steep grassy slope next to the wooded Dumgoyach Hill; or… From Carbeth, north along the A809, turn right up the B821 Ballachalairy Yett road for 1km and park where the path of the West Highland Way runs onto the hills. Follow this path for nearly ½-mile and where the path splits, bear left. Keep walking downhill for a few hundred yards, then go off-track towards the copse of trees. Climb over the gate and onto the grassy plain between this copse and the huge rounded Dumgoyach Hill. The stones are very close indeed…

Archaeology & History

This is a truly stunning site – not as much for the megaliths that are here, but for the setting in which they’re held. “Magnificent” is the word that rolled out of my mouth a number of times; whilst respected activist and ‘Organic Scotland’ creator Nina Harris said, quite accurately, “it’s Caras Galadhon in Lothlorien!” (or words to that effect) – and she hit the nail much better than I did!

Royal Commission 1963 sketch

Dumgoyach Stones (by Nina Harris)

A short line of large standing stones remains here, both upright and leaning, running NE-SW for 7 yards: seemingly a part of some other much larger monument in times long past—although very little else remains. The stones are set upon a rise of land, quite deliberately in front of Dumgoyach Hill (or Lothlorien, as Nina called it) almost as a temple or site of reverence. You’ve gotta see it to appreciate what I’m saying! Like some gigantic tree-covered Silbury Hill, the standing stones on this ridge possess an undoubted geomantic relationship with this rounded pyramid, all but lost in the sleep of local myths and land. A few yards away from the line of stones there is a slight rise in the land, seemingly giving weight to the idea that something else was living here: an architectural feature that Aubrey Burl (1993) thinks might have been “the facade of a chambered tomb” (neolithic in origin) and not merely a megalithic alignment. He may be right…

Close-up of the megaliths

Described briefly in J.G. Smith’s (1886) magnum opus on the Strathblane parish, antiquarian accounts of this impressive site seem curiously rare. One of the earliest recognised accounts was done by the Royal Commission (1963) lads who measured the site up with their usual diligence. Although getting the alignment of the stones wrong, the rest of their survey seems pretty accurate. They told that,

“There are five standing stones (A-E) arranged in a straight line… Three of the stones (A, B and C) are earthfast, while the other two (D and E) are recumbent. Stone A is of irregular shape and leans steeply towards the N. The exposed portion measures 4ft in height, 2ft 6in in breadth and 1ft 2in in thickness. Stone B stands upright, 6ft NE of A. It is a pillar of roughly rectangular section with an irregularly pointed top, and measures 5ft in height by about 2ft 6in in thickness. Stone C, also irregular in shape, 11ft 6in NE of B, is inclined so steeply to the NNE that it is almost recumbent. It measures 4ft 4in in height, 2ft 6in in breadth and 1ft in thickness. The remaining two stones lie on the ground between B and C. Stone D measures 5ft 5in in length, 3ft in breadth and 1ft 6in in thickness while stone E, which rests partly on D, measures 7ft 10in in length, 3ft 9in in breadth and 3ft in thickness.”

Aubrey Burl’s (1993) description of the site—which he called Blanefield—is another good synopsis of what is known historically and astronomically about the site. Assessing them in his detailed work on megalithic alignments, he said that,

“At Blanefield near Strathblane in Stirling a big stone, its longer sides aligned east-west, stands at an angle amongst a southwest-northeast line of four others, fallen, of which one just off the line seems to have been added this century. The setting has been presumed a collapsed four-stone row. Known also as Duntreath and Dumgoyach, the setting is slightly concave.

“‘This ruinous alignment indicates notches to the northeast and these show approximately the midsummer rising sun.’ ‘The standing stone has a flat face exactly aligned on a hill notch to the east,’ quite neatly in line with the equinoctial sunrises. These astronomical analyses would seem to confirm that Blanefield was undoubtedly a row set up by prehistoric observers to record two important solar events.

“Excavation in 1972 discovered signs of burning, flints and charcoal that yielded a C-14 assay of 2860±270 BC (GX-2781), c. 3650 BC, a time in the Middle Neolithic when chambered tombs were still in vogue, but an extremely early date for any stone row. This, coupled with Blanefield’s isolated position for a row in central Scotland, raises doubts about its origins.

“It is a lonely megalithic line, those nearest to it being over forty miles (64km) to the west in Argyll. Straddling a ridge overlooking the Blane Water it is arguable that the stones are relics of the crescent facade of a Clyde chambered long cairn with an entrance facing the southeast….”

Dumgoyach Stones, with Dumgoyne to the North

However, there was once another stone row close by, known as the old Stones of Mugdock. Burl then cites the proximity of four nearby neolithic long cairns not too far away, with the Auchneck tomb just 3½ miles (5.6km) to the west; although it seems that Nina Harris may have discovered another one, much closer still (TNA will have a preliminary report on this in the coming months).

Folklore

Local legend reputes that King Arthur was up and about in this part of the world, fighting in a battle nearby. And in J.G. Smith’s (1886) excellent work on the parish of Strathblane, he told that,

“The standing stones to the south-east of Dungoyach probably mark the burial place of Cymric or Pictish warriors who fell in the bloody battle of Mugdock.”

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, From Carnac to Callanish, Yale University Press 1993.

- Feachem, Richard, Guide to Prehistoric Scotland, Batsford: London 1977.

- Heggie, Douglas C., Megalithic Science: Ancient Mathematics and Astronomy in Northwest Europe, Thames & Hudson: London 1981.

- MacKie, Euan W., Scotland: An Archaeological Guide, Faber: London 1975.

- Ritchie, J.N.G., “Archaeology and Astronomy,” in Heggie, D.C., Archaeoastronomy in the Old World, Cambridge University Press 1982.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirling – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

- Smith, John G., The Parish of Strathblane, James Maclehose: Glasgow 1886.

- Thom, Alexander, Megalithic Sites in Britain, Oxford University Press 1967.

- Thom, A., Thom, A.S. & Burl, Aubrey, Stone Rows and Standing Stones – volume 1, BAR: Oxford 1990.

Acknowledgements: A huge thanks to Nina Harris, of Organic Scotland, for both taking me to these stones and sharing her photos for this site profile. Cheers Nina!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.