Rocking Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 37363 61280

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

On the outer southern edge of Kilbarchan parish—right near the ancient boundary line itself—this giant stone of the druids is seems to be well-known by local folk. Located about 40 yards away from the sacred ‘St Bride’s Burn’ (her ‘Well’ is several hundred yards to the west), it was known to have been a rocking stone in early traditions, but as Glaswegian antiquarian Frank Mercer told us, “the stone no longer moves.” The creation myths underscoring its existence, as Robert Mackenzie (1902) told us, say

“This remarkable stone, thought by some to have been set up by the druids, and by others to have been carried hither by a glacier, is now believed to be the top of a buried lava cone rising through lavas of different kind.”

The site was highlighted on the first OS-map of the area in 1857, but the earliest mention of it seems to be as far back as 1204 CE, where it was named as Clochrodric and variants on that title several times in the 13th century. It was suggested by the old place-name student, Sir H. Maxwell, to derive from ‘the Stone of Ryderch’, who was the ruler of Strathclyde in the 6th century. He may be right.

Folklore

Folklore told that this stone was not only the place where the druids held office and dispensed justice, but that it was also the burial-place of the Strathclyde King, Ryderch Hael.

References:

- Campsie, Alison, “Scotland’s Mysterious Rocking Stones,” in The Scotsman, 17 August, 2017.

- MacKenzie, Robert D., Kilbarchan: A Parish History, Alexander Gardner: Paisley 1902.

Acknowledgements: Big thanks to Frank Mercer for use of his photos and catalytic inception for this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Castleton (2), Cowie, Stirling, Stirlingshire

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 85494 88272

Also Known as:

-

Castleton 9 (van Hoek)

Getting Here

If you’re travelling from Stirling or Bannockburn, take the B9124 east to Cowie (and past it) for 3¾ miles (6km), turning left at the small crossroads; or if you’re coming from Airth, the same B9124 road west for just about 3 miles, turning right at the same minor crossroads up the long straight road. Drive to the dead-end of the road and park up, then walk back up the road 350 yards to the small copse of trees on your left. Therein, some 50 yards or so, zigzag about!

Archaeology & History

Petroglyphs can be troublesome things at the best of time: not only in their ever-elusive root meanings, but even their appearance is troublesome! This example to the east of Cowie in the incredible Castleton complex is one such case. It is undoubtedly a multi-period carving, probably first started in the neolithic period, added onto in the Bronze Age, and maybe even finished in the early christian period. You’ll see why!

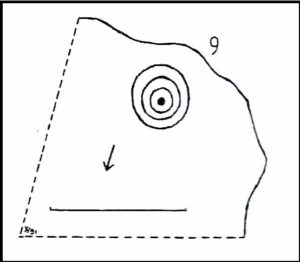

It’s been described several times in the past, with Maarten van Hoek (1996) telling how it was rediscovered,

“by Mrs Margaret Morris in 1986 in the birch-coppice at Castleton Wood. A fragment of outcrop rock with a distinct cup-and-three-rings, rather oval-shaped like others in the area.”

But as our own team found out, there’s more to it than that. Like many of the Castleton carvings, vital elements have been missed in the previous archaeological assessments. But it’s an easy thing to do. The carved design here almost ebbs and flows with daylight, shadows, changes in weather, bringing out what aboriginal and traditional peoples have always told us about rock itself, i.e., it’s alive, with qualities and virtues that can and do befuddle even that great domain of ‘objectivity’—itself an emergent construct of an entirely subjective creature (humans). But that’s what petroglyphs do!—whether they are part of a living tradition, or lost in our striving modernity, exhibiting once more that implicit terrain of animism. And this carving exemplifies it very clearly.

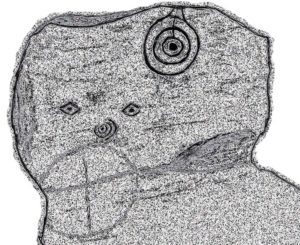

The primary visual design is the odd triple-ring, which isn’t quite as clear-cut as the earlier descriptions would have you think. In the drawing below by van Hoek (1996), three complete elliptical ‘rings’ are shown; whereas on its northern edge where the outer ring is closest to the rock edge, we find that the ‘ring’ has carved lines that run off and down the slope of the stone towards ground-level. It also seems that from the inner second-ring, a natural scar in the rock has been heightened by pecking, creating an artificial carved line running from near the centre and ‘out’ of the three rings. You can make this out in the accompanying photo, above.

Additionally we found two very faint carved ‘eyes’ or trapezoids pecked onto the stone, obviously at a much earlier date than the notable triple-ring—which could almost be modern! They would no doubt have excited the old archaeologist O.G.S. Crawford (1957), whose curious theory of petroglyphs was that they were images of some sort of Eye Goddess. Archaeo’s can come out with some strange ideas sometimes…

Fainter still was another triple-ring—albeit incomplete—with what appears to be a very small central cup-mark, just below and between the two ‘eyes’. It was first noticed by Paul Hornby when he was playing with the contrast settings on his camera, in the hope of getting clearer photos of any missing elements.

“Can you see this?” he asked. And although very faint indeed (on most days you can’t see it at all), it’s undoubtedly there: another multiple-ringer all but lost by the erosion of countless centuries, and older still than the ‘eyes’ above it. In all the photos we took of this stone, from different angles in different weathers (about 100 in all), this very faint triple-ring can only be seen on a handful of images. But it’s definitely there and you can see it faintly in the attached image (right) to the bottom-left.

A final note has to be made of a possible unfinished, large circular section with a cross carved into the natural feature of the stone, first noticed by Lisa Samson. It’s uncertain whether this has been touched by human hands (are there any geologists reading?), but it’s something that we’re noticing increasingly at more and more petroglyph sites. They’re not common, but it has to be said that we found two more man-made ‘crosses’ attached to multiple cup-and-rings near Killin just a few weeks ago. Also, folklore tells us that not far from this Castleton cluster, a christian hermit once lived….

References:

- Crawford, O.G.S., The Eye Goddess, Phoenix House: London 1957.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- van Hoek, M.A.M.,”Prehistoric Rock Art around Castleton Farm, Airth,” in Forth Naturalist & Historian, volume 19, 1996.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks as always to Nina Harris, Fraser & Lisa Harrick, Paul Hornby, Frank Mercer, Penny & Thea Sinclair, for their additional senses and input.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Sarah’s Stone, Borgie, Tongue, Sutherland

Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – NC 66791 60343

There’s no simple way to reach here – but the landscape alone makes the journey worthwhile. Roughly halfway along the A836 between Bettyhill and Tongue, take the minor road up to Borgie, past the recently revamped Borgie Hotel for half-a-mile (0.8 km) where, on your left, is Deepburn Cottage. On the other side of the road, on your left, go through the gate and follow the path uphill. It curves up and to the right where you hit some overgrown walling. Walk up and along this wall for nearly half-a-mile (it’ll feel like twice that!) and as you approach the crystal blue waters of Lochan a’ Chaorruin, veer right and start walking up the small Torrisdale Burn. Less than 200 yards along, you’ll see the large isolated rock on your left.

Archaeology & History

Previously unrecorded, this large boulder sitting above the edge of Torrisdale Burn was rediscovered by Sarah MacLean—hence its name—and has between five and nine cup-marks etched, primarily, on the topmost ridge of the rock. Its eastern steep-sloping face also has a cup-mark near the middle top-half of the stone. Apart from three of them (visible in the photos), the other cups aren’t very distinct and unless the lighting is right, you won’t see much here. This one is probably gonna be of little interest unless you’re a real hardcore petroglyph freak.

Further up this tiny winding glen we reach the faint cup-marked Thorrisdail Stone and a little further on is the impressive ritual site of Allt Thorrisdail.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Tun Well, Eccleshill, Bradford, West Yorkshire

Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – SE 1822 3593

Also Known as:

- Tunny Well

Archaeology & History

First mentioned in local history accounts from 1618—as the Tunwells—it was highlighted on the first OS-map of Eccleshill in 1851. Located on the aptly-named Tunwell Lane, it was a deep well covered by a large flat slab of stone, at the back-end the old Victorian mill. The stone was put there to prevent children falling into it. Some old locals thought the name of the place derived from a ‘tun’, or hundred, meaning it to be a hundred feet deep; although as A.H. Smith (1961) tells, tun could equally relate it to be one of Eccleshill’s town wells, of which there were several. It used to be one of the principal drinking supplies for the village and was said to rarely run dry. In William Ranger’s (1854) survey, he told this to be one of the sites to which local people relied in times of drought, where the land-owner allowed local folk to collect their supplies.

Folklore

The old cobbled Tunwell Lane was long ago supposed to be the haunt of a phantom black dog: a visionary precursor of death and Underworld guardian. Its spirit came and went into the deep well. I remember hearing tales of this when I was a young lad, as the old women who worked in the adjacent mills spoke of it. The ghost of a so-called ‘white lady’ was also said to walk along Tunwell Lane.

In more recent times, Val Shepherd (2002) included this in her short survey of wells in the area as being on “an alignment” with Eccleshill’s Moor Well and Holy Well. She thought “it may be part of a ley line”, but her alignment is inaccurate and doesn’t hit the spots.

References:

- Crapp, H.C. & Whitehead, Thomas, History of the Congregational Church at Eccleshill, Watmoughs: Idle 1938.

- Ranger, William, Report to the General Board of Health on a Preliminary Inquiry into the Sewerage, Drainage, and Supply of Water, and the Sanitary Condition of the Inhabitants of the Township of Eccleshill, George Eyre: London 1854.

- Shepherd, Val, Holy Wells of West Yorkshire and the Dales, Lepus: Bradford 2002.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 3, Cambridge University Press 1961.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Swithins Well, Rothwell, West Yorkshire

Healing Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 3442 2686

Also Known as:

- St. Swithin’s Well

Archaeology & History

Highlighted in the fields on the south-side of Rothwell village on the 1854 OS-map, Swithin’s Well was, according to historian Andrea Smith (1982), previously known as a holy well, dedicated to the obscure Saxon saint of the same name. Although no ‘well’ relating to St Swithin comes from any early texts, the field and farmhouse of ‘Swithins’ were cited in records from the Cartulary of Nostell Priory in 1270 CE; then subsequently in a variety of records throughout the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. According to Miss Smith (1982),

“The first recording of St Swithin’s Well, Rothwell…was on an estate map of 1792 (‘Plan of St. Clement’s lands in the parish of Rothwell in the County of York, two-third part of the tithes of corn and grain of which belong to the King in right of His Ducky of Lancaster’, PB), and the field-names arising from it—Swithin’s, Swithin’s Barn, Swithin’s Lane Close—serve to give an indication of the well’s past importance as a local landmark.”

When she visited the site around 1980, she reported finding,

“several wet patches running in a line westwards downhill, but the farmer’s wife seemed certain that this was a broken drain and nothing else could be seen in that field or neighbouring ones, which could have been the well.”

Very recently, the Wakefield pagan and antiquarian Steve Jones went to see if the well or any remains of it could still be seen and told us:

“We went looking for the well down a footpath but it was obviously filled in when a colliery was nearby in the early 20th century and (there is) no trace of any spring now.”

Another one’s bitten the dust, as they say…..

But we must note that the grand place-name authority, A.H. Smith (1962) found no references to St. Swithin here and instead suggested the name derived from the old Norse word, sviðinn, ‘land cleared by burning’, which is echoed in the old local dialect word swithen, ‘moorland cleared by burning’ (Smith 1956), and similarly echoed in Joseph Wright’s (1905) magnum opus, where—along with meaning ‘crooked, warped’—it means “to burn, superficially, as heather, wool, etc.” There is also a complete lack of any mention to the saintly aspects of this place in John Batty’s (1877) primary history book on Rothwell parish, and yet he cites numerous other springs and wells in the region that have fallen out of history.

References:

- Batty, John, The History of Rothwell, privately printed: Rothwell 1877.

- Jones, Steve, Personal communication, Facebook 27.08.2018.

- Rattue, James, “The Wells of St Swithun,” in Source, Summer 1995.

- Smith, Andrea, “Holy Wells Around Leeds, Bradford & Pontefract,” in Wakefield Historical Journal 9, 1982.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1961.

- Smith, A.H., English Place-Name Elements – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1956.

- Wright, Joseph, English Dialect Dictionary – volume 5, Henry Frowde: Oxford 1905.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Steve Jones of Wakefield for his informing us about the status of this site.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

St. Patrick’s Well (1), Dunruchan, Muthill, Perthshire

Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NN 77905 17365

Take the B827 road between Comrie and Braco. If you’re coming via Comrie, going uphill for 3.1 miles (5.1km); but if from Braco Roman Camp go along and eventually downhill for 6.6 miles (10.6km), watching out for the track to Middleton Farm by the roadside. Walk along for 125 yards, keeping your eyes peeled for the boggy ground below on your left. You’re there!

Archaeology & History

Immediately east of the prodigious megalithic complex of Dunruchan, bubbling up amidst the usual Juncus conglomeratus reeds, are the boggy remnants of St. Patrick’s Well—one of two such sacred wells dedicated to the early Irish saint in Muthill parish. We’re at a loss as to why this Irish dood has such sites in his name in this area. No doubt some transitional shamanic character was doing the rounds in this glorious landscape, muttering words of some neo-christian animism, eventually settling a mile from the great megalithic complex, perhaps hoping—and failing—to convert our healthy heathen populace into ways unwise.

Whatever he may have been up to, a small stone chapel was built hereby and, it was said, even a christian graveyard, to tempt folk away from the ancient plain of cairns whence our ancestors had long since buried their dead. But the christian’s chapel and graveyard has long since gone; and when historians before me had visited the place, St Patrick’s Well had also fallen back to Earth in the drier summers, taking the blood of the Earth back into Her body. The heathen megaliths still remain however, standing proud on the moorland plain in clear sight from these once healing waters, whose mythic history, on the whole, has long since been disregarded….

Folklore

St Patrick’s day on March 17—”a date very near the Spring Equinox,” as Mrs Banks (1939) reminded us—may have been the dates when the waters here were deemed particularly efficacious, although we have nothing in written accounts to tell us for sure. But in the 19th century Statistical Account we find that the site was “much frequented once, as effectual in curing the hooping cough.” E.J. Guthrie (1885) told of an ancient rite regarding the drinking of the waters for effect of the cure, saying:

“In the course of this century a family came from Edinburgh, a distance of nearly sixty miles, to have the benefit of the well. The water must be drunk before sunrise or immediately after it sets and that out of a “quick cow’s horn”, or a horn taken from a live cow, and probably dedicated to this saint.”

Also in Muthill parish, Guthrie told, St Patrick’s memory was held in such veneration that farmers and millers did not work on his day.

References:

- Banks, M. MacLeod, British Calendar Customs: Scotland – volume 2, Folk-lore Society: Glasgow 1939.

- Booth, C. Gordon, “St Patrick’s Well (Muthill Parish),” in Discovery & Excavation, Scotland, New Series volume 1, 2000.

- Guthrie, E.J., Old Scottish Customs, Thomas D. Morison: Glasgow 1885.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

St. Bride’s Well, London, Middlesex

Holy Well (covered): OS Grid Reference – TQ 3157 8111

Archaeology & History

Close to the centre of that corporate money-laundering place of homo-profanus that is the City of London, was once a site that represents the antithesis of what it has become. Tacked onto the southeastern side of St. Bride’s church along the appropriately-named Bride Lane, the historian Michael Harrison (1971) thought the Holy Well here had Roman origins. It “was almost certainly,” he thought,

“in Roman times, the horrea Braduales, named after the man who probably ordered their construction: Marcus Appius Bradua, Legate of Britain under Hadrian, and the British Governer in whose term of office the total walling of London was, in all likelihood, begun.”

This ‘Roman marketplace of Bradua’ that Harrison describes isn’t the general idea of the place though. Prior to the church being built, in the times of King John and Henry III, the sovereigns of England were lodged at the Bridewell Palace, as it was known. Mentioned in John Stow’s (1720) Survey of London, he told:

“This house of St. Bride’s of later time, being left, and not used by the Kings, fell to ruin… and only a fayre well remained here.”

The palace was eventually usurped by the building of St. Bride’s church. The most detailed account we have of St. Bride’s Well is Alfred Foord’s (1910) magnum opus on London’s water supplies. He told:

“The well was near the church dedicated to St. Bridget (of which Bride is a corruption; a Scottish or Irish saint who flourished in the 6th century), and was one of the holy wells or springs so numerous in London, the waters of which were supposed to possess peculiar virtues if taken at particular times. Whether the Well of St. Bride was so called after the church, or whether, being already there, it gave its name to it, is uncertain, more especially as the date of the erection of the first church of St. Bride is not known and no mention of it has been discovered prior to the year 1222. The position of the ancient well is said to have been identical with that of the pump in a niche in the eastern wall of the churchyard overhanging Bride Lane. William Hone, in his Every-Day Book for 1831, thus relates how the well became exhausted: ‘The last public use of the water of St. Bride’s well drained it so much that the inhabitants of the parish could not get their usual supply. This exhaustion was caused by a sudden demand on the occasion of King George IV being crowned at Westminster in July 1821. Mr Walker, of the hotel No.10 Bridge Street, Blackfriars, engaged a number of men in filling thousands of bottles with the sanctified fluid from the cast-iron pump over St. Bride’s Well, in Bride Lane.” Beyond this there is little else to tell about the well itself, but the spot is hallowed by the poet Milton, who, as his nephew, Edward Philips records, lodged in the churchyard on his return from Italy, about August 1640, “at the house of one Russel a taylor.”

In Mr Sunderland’s (1915) survey, he reported that “the spring had a sweet flavour.”

Sadly the waters here have long since been covered over. A pity… We know how allergic the city-minds of officials in London are to Nature (especially fresh water springs), but it would be good if they could restore this sacred water site and bring it back to life.

Folklore

Bride or Brigit has her origins in early British myth and legend, primarily from Scotland and Ireland. Her saint’s day is February 1, or the heathen Imbolc (also known as Candlemas). Although in christian lore St. Bride was born around 450 AD in Ireland and her father a Prince of Ulster, legend tells that her step-father (more probably a teacher) was a druid and her ‘saintly’ abilities as they were later described are simply attributes from this shamanic pantheon. Legends—christian and otherwise—describe Her as the friend of animals; possessor of a magickal cloak; a magickian and a healer; and whose ‘spirit’ or genius loci became attached to ‘sacred sites’ in the natural world, not the christian renunciation of it. St Bride was one of the primal faces of the great prima Materknown as the Cailleach: the Gaelic deity of Earth’s natural cycles, whose changing seasons would also alter her names, faces and clothes, as Her body moved annually through the rhythms of the year. Bride was (and is) ostensibly an ecological deity, with humans intrinsically a part of such a model, not a part from it, in contrast to the flawed judaeo-christian theology.

References:

- Foord, Alfred Stanley, Springs, Streams and Spas of London: History and Association, T. Fisher Unwin: London 1910.

- Gregory, Lady, A Book of Saints and Wonders, Colin Smythe: Gerrards Cross 1971.

- Harrison, Michael, The London that was Rome, Allen & Unwin: London 1971.

- McNeill, F. Marian, The Silver Bough – volume 2, William MacLellan: Glasgow 1959.

- Morgan, Dewi, St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, in the City of London, Blackfriars: Leicester 1973.

- o’ Hanlon, John, Life of St. Brigid, Joseph Dollard: Dublin 1877.

- Sunderland, Septimus, Old London Spas, Baths and Wells, John Bale: London 1915.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Jim Craven’s Well, Thornton, West Yorkshire

Sacred Well: OS Grid Reference — SE 0967 3251?

Archaeology & History

Another well with considerable supernatural renown was this little-known site near the old village of Thornton, on the western outskirts of Bradford. We’re not 100% sure about its exact location, but the grid-reference cited here is of an old ‘Well’ that was highlighted on the first Ordnance Survey map of the region, at the end of solitary path which led to it and nowhere else. Our only documentary information comes from Elizabeth’s Southwart’s (1932) fine old book on the folk life of the old village, as it once was. At a place once known as Bent Ing Bottom, just south of the old village, is where it used to be known. The name of this Well is also curious, as no historian has yet worked out who the ‘Jim Craven’ was, nor what his relationship to the site might have been. It’s the folklore of it, however, which brings it the attention it deserves.

Folklore

In Elizabeth Southwart’s (1923) work, she told us that the place once known as “Bent Ing Bottoms have lost their romance.” She continued:

“Whether the golfers have driven it away—for the fields now form part of the Thornton Golf Links—or whether the advance of modernity in other forms is to blame, it is difficult to say. Once they were the haunts of “Peggy-Wi-T’-Lantern” and the Bloody-tongue. Peggy, a dame in a white mob cap, kilted skirt and white stockings, walked about with a lantern, enticing the unwary traveller to his doom. She was given to wandering, for, they say, Jim Craven Well, half a mile away, was a place to be avoided after nightfall.

“The Bloody-tongue was a great dog, with staring red eyes, a tail as big as the branch of a tree, and a lolling tongue that dripped blood. When he drank from the beck (known as the Pinch Beck, PB) the water ran red right past the bridge, and away down—down—nearly to Bradford town. As soon as it was quite dark he would lope up the narrow flagged causeway to the cottage at the top of Bent Ing on the north side, give one deep bark, then the woman who lived there would come out and feed him. What he ate we never knew, but I can bear testimony to the delicious taste of the toffee she made.

“When the dark was coming we used to sit on the filled-in pit, which makes a hump in the middle of the field, and wait for him. The sun would sink redly, through the arches of the viaduct, the trees that lined the beck would grow an ever darker green until they became black, the beck would begin to gurgle and gulp in a queer way; and down in the hollow we would hear a whimper, a whine, a moan, a snarl. Then, with scalps and spines playing queer tricks, we would wait and wait. But none of our little band ever saw him, except one girl, and she saw him every time.

“One Saturday a girl who lived at Headley came to a birthday party in the village, and was persuaded to stay to the end by her friends, who promised to see her ‘a-gaiterds’ if she would. As soon as the party was over the brave little group started out. But when they reached the end of the passage which leads to the fields, and gazed into the black well, at the bottom of which lurked the Bloody-tongue, one of them suggested that Mary should go alone, and they would wait there to see if anything happened to her.

“Mary was reluctant, but had no choice in the matter, for go home she must. They waited, according to promise, listening to her footsteps on the path, and occasionally shouting into the darkness:

““Are you all right, Mary?”

““Ay!” would come the response.

“And well was it for Mary that the Gytrash had business elsewhere that night, for her friends confess now that at the first sound of a scream they would have fled back to lights and home.

“We wonder sometimes if the Booody-tongue were not better than his reputation, for he lived there many years and there was never a single case known of man, woman or child who got a bite from his teeth, or a scratch from his claws. Now he is gone, nobody knows whither, though there have been rumours that he has been seen wandering disconsolately along Egypt Road, whimpering quietly to himself, creeping into the shadows when a human being approached, and, when a lantern was flashed on him, giving one sad, reproachful glance from his red eyes before he vanished from sight.”

Southwart later tells us that the ghostly dog travelled into the north and vanished. From the description she gives of the children walking their friend to “the end of the passage which leads to the fields, and gazed into the black well, at the bottom of which lurked the Bloody-tongue,” I can only surmise that the solitary well shown on the very first OS-map of Thornton at the coordinate given above is the place in question.

The ‘Bloody Tongue’ is first mentioned in Yorkshire folklore, I think, by Roger Storrs, in his article on holy wells in 1888, where he tells it to be one of the mysterious beings that live, usually at the bottom of the waters and almost universally used “to deter children from playing in dangerous proximity to a well.”

From the description of the waters turning red when the ghostly dog drank from it, we have a mythic account of when the waters occasionally turned red from the iron-bearing waters (chalybeate) which, obviously, wasn’t like this at all times. Whether this was a sporadic, unpredictable flow of iron in the waters, or a cyclical pattern of the water-flows, we are not told (which would imply, moreso, that it was sporadic). The folklore about this ghost and its appearance with another elemental creature along an old straight track running north from Upper Headley Hall to Thornton is intriguing—as in many old pre-christian traditions, North is the airt, or direction, representing Death; and black dogs are traditionally guardians of underworld treasures in the land of the Dead. With the plethora of other animistic folktales once known in this district (boggarts or goblins were known in nearby woods, wells and farms) it is likely that the origin of such folklore dates way back into antiquity.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of West Yorkshire, forthcoming

- Southwart, Elizabeth, Bronte Moors and Villages: From Thornton to Haworth, John Lane Bodley Head: London 1923.

- Storrs, Roger, ‘Legends and Traditions of Wells,’ in Yorkshire Folk-lore Journal – volume 1 (ed. J. Horsfall Turner) 1888.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Holy Well, Bingfield, Northumberland

Holy Well (destroyed): OS Grid reference – NZ 01 74

Archaeology & History

We add this site in the hope that a local historian may be able to rediscover its whereabouts. Long since lost, the last account of it was mentioned in notes by the prodigious northern antiquarian John Crawford (1899) in his vast work on Northumbrian history. Its whereabouts is vague as its final writings were scribed in The Black Book of Hexham in 1479 CE, where it was told that “the Haliwell flat (was) lying between the vill of Bingfield and Todridge.” Mr Crawford told us it was somewhere in this area:

“The south-west extension of Grundstone Law is a tract of poor pasture land called Duns Moor; and rising opposite to it on the north-east is the Moot Law, in Stamfordham parish, the valley between being watered by an affluent of the Erring burn.”

The Well was included in Binnall & Dodds’ (1942) fine survey, with no additional notes. To my knowledge, no more is known of the site.

References:

- Binnall & Doods, “Holy Wells in Northumberland and Durham – Part 2,” in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, July 1942.

- Hodgson, John Crawford, The History of Northumberland – volume 4, Andrew Reid: Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1899.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

St. Ninian’s Well, Stirling, Stirlingshire

Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NS 79690 93012

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 46210

- St. Ringan’s Well

A short distance south out of Stirling town centre, along Port Street where it meets with Ninian’s Road, walk across at the traffic lights then turn immediately left down Wellgreen Road. Barely 100 yards down (before you reach the roundabout), note the path on your right. Walk along here and as it bends round into the car-park, look to your left and see the small ivy-covered building hiding away in below you, with an information plaque at its side.

Archaeology & History

“St Ninian’s” is a district unto itself on the south side of the ancient city of Stirling—and it has this holy well (and the demolished chapel that once stood by its side) to thank for this. James Johnston’s (1904) place-name study of the region showed that it had acquired its association with St Ninian as early as 1242 CE when it was described, “Ecclesia Sancti Niniani de Kirketoune.” It was mentioned again in 1301 CE as the site of “Saint Rineyan”, or St Ringan, which was the other name given to this saint who spent much of his time at Whithorn, Galloway, where he “preached the gospel among the southern Picts.” (Attwater 1965)

At some later date, Ninian is thought to have ventured north and sanctified this already renowned water source which, in his day, would have been open and surrounded by ancient trees and an abundance of wild flowers and healing plants. But today, typically, it is hiding almost secretly away, behind locked doors and not in view for the general public. This needs to be changed! Standing outside of the unkempt and overgrown building, you can faintly hear these ancient waters still flowing within their darkened enclave.

It has been described in a number of local history books down the years, but a lot of the old stories and traditions have sadly moved into forgotten memories… The first major description of the site was by J.R. Walker (1883) who wrote freshly about it soon after his visit—despite being “disappointed” with the architectural features of the building built over the well; which is hardly the right attitude as far as I’m concerned! The waters, their natural environment, feeling and genius loci are the primary features to sacred wells—nottheir dissolution, nor the artifice of humans to contain and reduce the natural world at such a place! But, this aside: for the architects amongst you, here’s what Walker had to say about the well-house:

“Mr T.S. Muir, in his Characteristics of Old Church Architecture, mentions it as “a large vaulted building with a chamber above it, which is supposed to have been a chapel.” From this notice I was led to think something of interest would be found in the chamber; but as will be seen by the drawing…it is utterly destitute of any feature worthy of particular notice. On looking at the surroundings, however, which are all modern, and mostly new houses and streets in course of erection, I came to the conclusion that at no distant date the well was doomed, and that consequently I had better make a correct drawing of it.

“The lower chamber measures 16 feet by 11 feet 1 inch, and is covered with a vault running from end to end, measuring from floor to springing 2 feet 9 inches, and from floor to crown of arch 6 feet. At the end where the spring rises there is a square recess 1 foot 9 inches high and 1 foot 7 inches wide and 17 inches deep; and at the other end two recesses, the largest measuring 2 feet 7 inches in height, 1 foot 4 inches wide and 1 foot 4 inches deep, the other 8 inches high, 8 inches wide, and 8 inches deep. To what purpose these have been put I have formed no idea; they are on an average 12 inches from the floor to the sill. The side walls are 2 feet 9 inches thick, and the end gable 3 feet; the other gable, between the well chamber and the adjacent building, being about 2 feet 3 inches. The room above is the same size as the vaulted chamber below, and is divided by timber partitions to form a dwelling-house. There is an ordinary fireplace and press in the gable; the press, however, does not go down to the floor, but is simply a recess or “aumbry,” such as we see in old Scotch houses.

“The roof seems to have been renewed at no distant date, although some of the timbers are, without doubt, home-grown. The ground rises rapidly to the back, so that the entrance door to the house is level with the top of the vault; this door is simply splayed in the Scotch manner, with a square lintel over, and a relieving arch inside. The door to the well chamber is also splayed, and in like manner the windows; the largest window has been altered, and a new projecting sill put in.

“At present the well is used for washing purposes, and must have been so for a considerable length of time, if we may judge from the table of rates affixed to the building; and a channel has been formed down one side and along the bottom end to carry away the water, the floor being paved with stones. The vault inside is roughly dressed, very little labour seemingly having been bestowed upon it.

“In the New Statistical Account it is suggested that the chamber was used as a bath, and it also states that, “it is celebrated for its copiousness and its purity. It is a hardish water, but of low specific gravity, and much used for washing. It has been calculated that were all the waters proceeding from this spring forced into the pipes that supply the town, it would afford every individual not less than 14.03 gallons per twenty-four hours. Its temperature is very cold and it exhibits muriate of lime and sulphate of lime. It is also much used for brewing.”

“Externally the building is roughly cast, or in Scottish phraseology, harled.”

A few years later when J.S. Fleming (1898) wrote an account of the place in his survey of local holy wells, he described a number of other historical elements not included in Walker’s (1883) account, telling:

“RINGAN” is stated to be the Scoto-Irish form of Saint Ninian’s name. He is alleged to have come from Ireland in the fifth century. St. Ringan’s Chapel was one of three attached to St. Ninians, the others being at Skeoch—dedicated to the Virgin Mary—and at Cambusbarron. The remains of St. Ringan’s Chapel, a simple, barrel-vaulted chamber, 11 feet by 14 feet, built over the spring, are situated a few yards off Pitt Terrace, the upper walls having been built, in 1731, by order of the Stirling Town Council, and formed into a house for the convenience of the town’s washerwomen. A niche in the north-east wall has evidently been made to hold the image of the Saint; while there has also been a piscina in the same wall. The flow of water is enormous, and enters the building from under the south-west gable, and after passing through the little chamber, flows out at the east wall. In 1740, the Town Council, considering the large volume of water of some value, entertained the idea of having it conveyed into the town by means of pipes, and consulted an Edinburgh engineer with regard to the feasibility of the project. Nothing resulted from their efforts, however. The water of this spring is stated to be so cold in summer that people cannot stand in it for any length of time; while in winter, again, it is so warm that it rapidly thaws whatever is thrown into it. Smoke rises from it at times, hanging over it like a vapour on a frosty morning. These characteristics indicate that the waters must issue from a great depth in the ground.

“This Chapel was apparently held in high repute by King James IV., as in the Exchequer Rolls we find the following entries: — “1497, April 24. — Item to the King’s offerand in Saint Ringans Chapel, besid Strivelin, 14/.” ” Samen day to Schir Andro to get say a hental of messes of Saint Ringans, 20⋅/.”

The site was mentioned in the standard surveys of MacKinlay (1893) and Morris (1981), but with very little additional information.

Folklore

St. Ninian’s festival date is September 16, but I’ve been unable to find any information about any practices here for that date. However, in 1659, St Ninian’s Well was mentioned as a site used in what the deluded criminal courts of the period called “a case of witchcraft”, against one Bessie Stevenson. The lady concerned told of performing quite normal herbal practices and similar animistic healing traditions, typical of those found universally in peasant cultures, but which the crazed church-goers saw as something completely different. Bessie told that for people who were either sick or bewitched, she would wash their clothes in the running waters of St. Ninian’s Well, to wash away any disease and cure the said person. It is likely that the waters here were commonly used for such rites, much as the christian priesthood still do at many ‘holy waters’ to this very day. Indeed, of the sacred waters here, St. Ninian himself was said to “have endowed it with peculiar virtues.” (Roger 1853)

References:

- Attwater, Donald, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, Penguin: Harmondsworth 1965.

- Fleming, J.S., Old Nooks of Stirling, Delineated and Described, Munro & Jamieson: Stirling 1898.

- Johnston, James B., The Place-Names of Stirlingshire, R.S. Shearer 1904.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Mould, D.D.C.P., Scotland of the Saints, Batsford: London 1952.

- Reid, John, The Place-Names of Falkirk and East Stirlingshire, Falkirk Local History Society 2009.

- Roger, Charles, A Week at Bridge of Allan, Adam & Charles Black: Edinburgh 1853.

- Ronald, James, Landmarks of Old Stirling, Eneas Mackay: Stirling 1899.

- Simpson, W.D., St. Ninian and the Origins of the Christian Church in Scotland, Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh 1940.

- Walker, J. Russel, “‘Holy Wells’ in Scotland,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol.17 (New Series, volume 5), 1883.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian