Souterrain: OS Grid Reference – NO 2529 3738

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 30539

- The Cave

- Pitcur II (Wainwright)

Getting Here

Pitcur souterrain entrance

From Coupar Angus, take the A923 road southeast for nearly 2½ miles where you reach the crossroads. Keeping walking along the A923 for just over 300 yards, then where you come to the second field on your left, follow the line of fencing the slope until you reach an overgrown fenced section. It’s in there!

Archaeology & History

This is a mightily impressive site, which I’ve been looking forward to experience for many an age. And—despite Nature covering it in deep grasses—it was even better than any of us anticipated. Souterrains are ten-a-penny in this part of Scotland, but this one’s a beauty! Here, dug 6-8 feet into the ground are at least two long curvaceous passageways, linked by another stone-roofed passageway—with the longest central passage leading at one end into a completely covered stone hallway, whose end is blocked by a massive fall of earth. Outside this entrance, laid on the ground, is what looks like a possible old stone ‘door’ that may have once blocked the entrance, now fallen into disuse. It is too small to have been a roofing stone. In the walling just outside the entrance, on your left, you will see a faint cup-marked stone (Pitcur 3:5) and a larger cup-and-ring stone (Pitcur 3:6), both just above ground-level.

Inside looking out (photo by Frank Mercer)

Outside looking in (photo by Frank Mercer)

The site is evocative on so many levels: not least because we still don’t know what the hell it was used for. The over-used idea that souterrains were cattle-pens makes no sense whatsoever here; the idea that they were food storage sites is, I suppose, a possibility; that they were possible shelters for people during inter-tribal raids is another; and equally as probable is that the deep dark enclosed construction was used by shamans, or neophytes enclosed for their rites of passage. Iron Age archaeology specialist Ian Armit (1998) thought there may well be some as yet undiscovered “timber roundhouse” associated with this souterrain, awaiting excavation. He may be right. When we came here the other week we found previously unrecorded cup-and-ring carvings, at a site already renowned for decent petroglyphs. A post-winter visit will hopefully bring us more finds.

The general history of this strange site is captured in Wainwright’s (1963) survey of souterrains, in which he wrote:

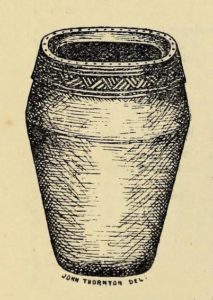

“Pitcur II was discovered in 1878 when a large stone, hit by a plough, was removed to reveal an underground passage. Mr John Granger, tenant of Pitcur farm, excavated the souterrain himself, and twenty-two years later his son, Mr A. Granger Heiton, said that the only objects found by members of his family were ‘a small red clay bowl of Samian ware in pieces’ and ‘a Roman coin.’ The latter, according to David MacRitchie, ‘has been lost sight of’. Mr Granger Heiton also told McRitchie that ‘one or two other coins were reported as having been found’, but were not seen by his father.

“As an excavation, Mr Granger’s effort seems to have been unsatisfactory by any standards, and it was followed by a ‘supplementary excavation’ conducted by Mr R. Stewart Menzies. This was more successful as a relic-hunting operation, if not as an archaeological excavation, for between one hundred and two hundred finds are reported, including ‘a bronze pin’ and ‘a quantity of stones, beads, etc.’ But these too ‘seem to have been mislaid.’

Newly-found Pitcur 3:2 carving

Curiously Mr Wainwright made little mention of the impressive petroglyphs within this complex, save to say that “they were too heavy to be removed and ‘mislaid’.” There are at least seven of them at Pitcur-3: four complex cup-and-ring designs and three basic cup-marked stones (described individually in separate site-profiles). They have all been incorporated into the walls and roofing stones. At least one of these is so eroded (Pitcur 3:2) that there is little doubt it was re-used from a now-lost neolithic structure; the rest may have been from Bronze Age sites (also lost) and their respective lack of erosion shows they have been inside this Iron Age structure, away from Nature’s wind and weathering effects. It is likely that the re-use of these carvings in Pitcur-3 was of significance to the builders; although we cannot be sure as to what their function may have been within the souterrain. It’s quite possible that some form of ‘continuity of tradition’ as posited by David MacRitchie (1890) was in evidence, over that huge time scale from the neolithic into the Iron Age, relating specifically to the animistic plinth implicit in all early agrarian cultures.

But the first real overview of the site was written at the end of the 19th century by David MacRitchie (1900), over twenty years after its rediscovery in 1878. His account was a good one too:

“The Pitcur house consists of one long subterranean gallery, slightly curved throughout most of its length, and bending abruptly in a hook shape at its western end. From this western end a short broad gallery or room goes off, curving round the outside of the ‘hook.’ The length of the main gallery, following the medial line, and measuring from the extreme of the entrance at either end, is almost 190 feet; while the subsidiary room is 60 feet long. For most of its length, this subsidiary room is 10 feet wide, measuring at the floor level. On account of this unusual width, it is reasonable to suppose that its roof was of timber; for although the walls slightly converge at the top, reducing the intervening space to 8 or 9 feet, the span is still so great that a flagged roof would scarcely have been practicable. To be sure, the walls might have been raised several courses higher, in the usual ‘ Cyclopean arch,’ and thus the interval to be bridged would become sufficiently narrowed at a height of say 12 feet. But there is no indication that the walls of any portion of this earth-house ever rose higher than the present level of their highest parts. Thus the inference is that this subsidiary room may have been roofed with timber.”

Modern groundplan (after RCAHMS, 1994)

MacRitchie’s 1900 groundplan

It may, but we have no remaining evidence to tell us for sure. MacRitchie cited possible evidences from elsewhere to add weight to this thought, but had the humility to leave the idea open, telling simply how “no vestige of a roof is visible at the present day, and the whole of this side room is open to the sky,” as with the majority of this entire souterrain. In my opinion, more of it would have been roofed in stone slabs, but these would seem to have been robbed. Certainly a well-preserved cup-marked stone (Pitcur 3:3) laying up against one of the walls appears to have slid from its topmost covering position into where it now rests in the passageway (near ‘b‘ in MacRitchie’s plan).

Continuing with Mr MacRitchie’s account, he (like most of us) found the underground section most impressive, telling:

“This covered section is unquestionably the most interesting and instructive of the whole building; for, as already stated, the other parts are more or less ruined and roofless. A few remaining flags lying in the unroofed part of the main gallery show, however, that it once possessed the usual stone roof throughout its entire length. This was rendered possible by the comparative narrowness of the main gallery, the width of which on the floor averages about 6 feet. The greater breadth of the subsidiary gallery will be realised by glancing at the cross section, a-b in the plan.

“The Pitcur earth-house had at least three separate entrances, namely, at the points h, i, and j. The subsidiary room appears also to have had an independent connection with the, outside world, at the point g, and perhaps also f, though the latter may only mark a fireplace or air-hole, for the condition of the ruin makes it difficult for one to speak with certainty. The entrance at i, which slopes rapidly downward, is roofed all the way to d; and consequently this short passage remains in its original state.

“Within the covered portion, and quite near its entrance, a well-built recess (e in the plan) seems clearly to have been used as a fireplace, although the orifice which presumably once connected it with the upper air is now covered over. Another and a smaller recess in the covered portion (k in the plan) can hardly have been a fireplace, and it is difficult to know what it was used as.

“One other point of interest is the presence of two cup-marked stones (p and q on the plan). Of these, the former is lying isolated on the surface of the ground near the entrance i, while the latter forms one of the wall stones beside the doorway c.”

‘Fireplace’ near the entrance

The internal ‘cave’ section has that typical damp smell and feel to it, beloved of underground explorers. As we can see in MacRitchie’s old photo of the site, the seeming ‘fireplace’ that he mentions is very obvious. Frank Mercer posited the same idea about this underground alcove when he first saw it, and it makes a lot of sense. On the left-upright stone in the photo (right) you can just make out a single cup-marking (Pitcur 3:7) which we found when we visited; another one may be on the inside edge of the same fireplace. If you climb up on top of the souterrain close to where the opening of the fireplace would have been, you’ll see the impressive Pitcur 3:5 petroglyph; whilst the Pitcur 3:1 carving is difficult to see (though Mr Mercer noticed it), just above ground-level, beneath the covering stone ‘m‘ in MacRitchie’s plan. All in all, a bloody impressive place!

Folklore

In earlier centuries the site was known locally as The Cave, yet considering how impressive it is, folklore and oral tradition seem sparse. Even David MacRitchie (1897) struggled to find anything here. But in one short article he wrote for The Reliquary, he thought that stories of little-people may have related to Pitcur-3:

“A tradition which a family of that neighbourhood has preserved for the past two centuries, has, in the opinion of the present writer, a distinct bearing upon the “cave” and its builders.

“This is that, a long time ago, a community of “clever” little people, known as “the merry elfins,” inhabited a “tounie,” or village, close to the place. The present inheritors of the tradition assume that they lived above ground and do not connect them at all with this “cave,” of whose existence they were unaware until a comparatively recent date. But, in view of a mass of folk-lore ascribing to such “little people” an underground life, the presumption is that the “tounie” was nothing else than the “cave”. This theme cannot be enlarged upon here; but a study of the traditions relating to the inhabitants of those subterranean houses will make the identification clearer.

“It may be added that the term “Picts’ house” applied to the Pitcur souterrain, is in agreement with the inherited belief, so widespread in Scotland, that the Picts were a people of immense bodily strength, although of small stature.”

References:

- Armit, Ian, Scotland’s Hidden History, Tempus: Stroud 1998.

-

Barclay, Gordon, “Newmill and the ‘Souterrains of Southern Pictland’”, in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 110, 1980.

-

- Mackenna, F.S., “Recovery of an Earth House”, in The Kist, volume 4, 1972.

- Mackie, Euan, Scotland: An Archaeologial Guide, Faber: London 1975.

- MacRitchie, David, The Testimony of Tradition, Kegan Paul: London 1890.

- MacRitchie, David, “Pitcur and its Merry Elfins,” in The Reliquary, 1897.

- MacRitchie, David, “Description of an Earth-house at Pitcur, Forfarshire,” inProceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 34, 1900.

-

Neighbour, T., “Pitcur Souterrain (Kettins parish)”, in Discovery & Excavation Scotland, 1995.

-

Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, South-East Perth: An Archaeological Landscape, HMSO: Edinburgh 1994.

-

Wainwright, F T., The Souterrains of Southern Pictland, RKP: London 1963.

-

Warden, Alex J., Angus or Forfarshire: The Land and People – Descriptive and Historical – 5 volumes, Charles Alexander: Dundee 1880-1885.

-

Acknowledgements: This site profile would not have been made possible were it not for the huge help of Nina Harris, Frank Mercer & Paul Hornby. Huge thanks to you all, both for the excursion and use of your photos in this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.