Cup-and-Ring Stone (lost): OS Grid Reference – NT 269 419

Also Known as:

- Kittlegairy Burn

Archaeology & History

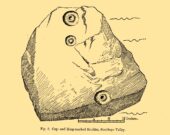

An apparently isolated cup-and-ring stone was found on the hills north of Peebles at the end of the 19th century by the renowned Scottish megalith explorer, Fred Coles. (1899) He was having a look at some of the hillforts in the area and—as some of us tend to do—he began meandering off-track, down streams, through bogs and as a result came across the carving that’s illustrated here. It’s subsequently become “lost” in the hills, but it shouldn’t be too difficult to locate, as the description he gave of its whereabouts is a pretty good one. He told us:

“A very little over one mile and a quarter up the valley, measuring from the road at Kerfield Cottage, a tiny rivulet called Kittlegairy Burn trickles down from the SE into the main stream. On the hill to its east, and about 450 feet higher, are the remains of a fort, one of a series of three crowning prominent heights along this side of the valley. Down the main stream from Kittlegairy Burn is a large ruined sheep-shelter called Soonhope. Nearly midway between these two points a deep curve has been hollowed out of the E. bank; and, at the foot of this rather high gravel bank, half immersed in the stream, lies the block of stone with the cup-and ring-marks. They were discovered, 14th September 1896, by my daughter, Helen, on crossing the stream; and we at once proceeded to make a measured drawing, a reproduction of which is given here…. The depth of the rings in proportion to their width is the one most noticeable feature; next, the extreme thinness of the intervening ‘neck’; but, on a minute and careful examination of the nature of the stone itself, taking into consideration that its angularity and sharpness of edge and the absence of moss or even of confervoid growths on its surfaces went against the possibility of its being truly waterworn.”

The rock had obviously fallen from its original position above the burn. Today, the entire area where this stone exists has been covered by a huge forestry plantation, but if any rock art fanatics from the Peebles area get bored one day and have nothing to do…..

References:

- Coles, Fred, “Notices of the Discovery of a Cist and Urns at Juniper Green, and of a Cist at the Cunninghar, Tillicoultry, and of some Undescribed Cup-marked Stones’, in Proceedings Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 33, 1899.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Cup-and-Ring and Similar Early Sculptures of Scotland; Part 2 – The Rest of Scotland except Kintyre,” in Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, volume 16, 1969.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The cup-and-ring marks and similar sculptures of Scotland: a survey of the southern Counties – part 2,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 100, 1969.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.