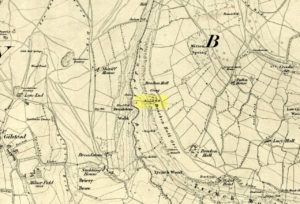

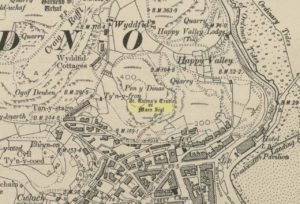

Stone Circle (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NO 0808 5985

Archaeology & History

Kirkmichael parish was an area that was described by George Chalmers (1887) as possessing “a vast body of Druid remains,” there being “a number of Druid cairns in the vicinity of Druidical circles.” As we know, the term ‘druid’ has long fallen out of favour; and with it in this area, the sites themselves have taken a similar fate.

Found just south of the village, on raised ground 100 yards west of the river, this stone circle is not listed in any of the archaeological catalogues, but its existence was thankfully recorded in one of the essays by regional historian Charles Fergusson. He told us that,

“one of these Druidical circles stood at Tom-a-Chlachan — the Hillock of Stones — where the Manse of Kirkmichael now stands, and there two thousand years ago our rude ancestors worshipped, according to their faith, in their circle of stones; and there, as elsewhere, when the pioneers of Christianity came to the district, they found it expedient to place their new church where the old circle of stones had stood, so the first church of St Michael was reared where the old clachan stood, on what the natives already considered holy ground.”

In the same tradition (but this time, without the destruction), on the other side of the River Ardle from here, what was once known as a heathen well later became known as the Priest’s Well.

References:

- Chalmers, George, Caledonia – volume 1, Alexander Gardner: Glasgow 1887.

- Fergusson, Charles, “Sketches of the Early History, Legends and Traditions of Strathardle and its Glens – part 5,” in Transactions of Gaelic Society Inverness, volume 21, 1899.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian